[ad_1]

The first time I saw former New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman speak was two days after President Donald Trump was elected. A friend invited me to join her at a gathering of prominent progressive organizers and allies in Brooklyn, and I sat in a living room listening to artists, grassroots organizers and politicians speak candidly and emotionally about what could and should come next.

One of those politicians was Schneiderman, who resigned Monday after a story detailing disturbing allegations of physical, verbal and mental abuse of four women was published in The New Yorker. (Schneiderman responded to the allegations on Twitter, saying that: “In the privacy of intimate relationships, I have engaged in role-playing and other consensual sexual activity. I have not assaulted anyone. I have never engaged in non-consensual sex, which is a line I would not cross.”)

Two things about that meeting are prominent in my memory. The first is that the attorney general was magnetic. Here was a powerful white man vowing at the dawn of the Trump presidency to use his platform and position to advocate for the rights of marginalized people, specifically women. Here was one of the good ones.

The impression Schneiderman made in that living room helped create a general air around him of irreplaceability. Trump was in office, and we needed Democrats like Schneiderman, powerful liberal men who seemed to get it, to hold the line. That’s what a friend told one of the accusers in urging her to stay quiet, after all — that Schneiderman was “too valuable a politician for the Democrats to lose.”

The second thing that stands out in my mind is who co-organized the meeting. It was author and activist Tanya Selvaratnam, one of the four accusers. Selvaratnam now says Schneiderman slapped, choked, threatened and belittled her over the course of their romantic relationship. He abused her, allegedly, while using her position as a feminist activist to help him cultivate a reputation for being an indispensable ally. Thus the victim would be made to participate in the invention of the alibi.

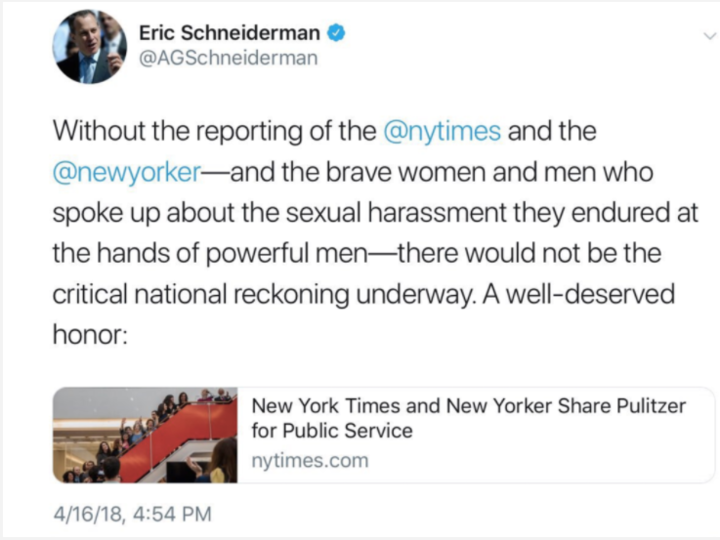

A lot of women apparently were taken in over the years. Schneiderman readily accepted the donations of feminists, their endorsements, their votes, explicitly positioning himself as a man who would stand in the way of any threats to women’s bodily autonomy. He supported Planned Parenthood and vowed to protect the legacy of Roe v. Wade. His office published a “Know Your Rights” brochure to increase domestic violence awareness. As a state senator, he introduced legislation to make intentional strangulation to the point of unconsciousness a violent felony, calling it a “heinous crime” that “no one is immune from accountability for committing.” In 2010, after the New York chapter of the National Organization for Women endorsed his candidacy for attorney general, Schneiderman issued a statement claiming that he would “never stop standing up for women’s rights ― whether it’s safeguarding a woman’s right to choose or protecting victims of domestic abuse.” He lauded the women and men who told their Me Too stories just weeks ago, praising The New York Times and New Yorker for setting off a “critical national reckoning.”

In his rhetoric and in his political commitments, Schneiderman was a model ally. And yet privately, according to the women’s accusations, Schneiderman spent years abusing the very people on whose behalf he purported to advocate. The four women who spoke to Jane Mayer and Ronan Farrow describe a man who mocked their ambitions, looks and political organizing, slapped them across their faces so hard that he’d leave marks, spat on them and intentionally choked them, though never to the point of unconsciousness. Selvaratnam, who dated the former attorney general from 2016 to 2017, compared the dissonance in Schneiderman’s public-facing feminist persona and private abuses to Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

Kristen Houser, chief public affairs officer at the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, said that the Schneiderman accusations point to a larger pattern of powerful men, specifically those involved in law enforcement, who leverage their positions to create a self-protective shield and keep their victims feeling powerless and silent.

“What better way to hide your own behaviors and ensure that no one will believe the victims if they come forward than being an outspoken advocate, tough on this kind of crime?” she explained. “All victims face the barriers of shame and stigma. When that is coupled with political power, social power, prestige, there is an entire additional set of barriers that will keep people silent.”

Too valuable. In a world where men still hold the vast majority of public offices, and therefore the vast majority of political power, women’s safety is still considered acceptable collateral damage ― even when the purported goal is to keep someone in office who is an advocate for women on the whole.

When women express a desire for power and influence, especially within the political sphere, a commitment to “women’s issues” is largely treated as a given, or even a potential liability. For progressive men, it’s a great boost, an easy way to make a name and build a career. And when these beacons of allyship get concrete power, women are not only expected to be grateful but also to protect them at all costs. This is why one of Schneiderman’s alleged victims worried that reporting that he smacked her across the face during a casual sexual encounter might “jeopardize” the “good things” he was doing as attorney general. It’s why a major Democratic donor threatened to reconsider supporting Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and other female senators who urged Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.) to resign; Franken likewise was said to be too valuable to be dropped. It’s why women often feel that they have to stay silent about abuse for fear of retribution, while male perpetrators arrogantly wear Time’s Up pins and tweet their support for #MeToo.

No political figure is irreplaceable. No political career is worth whatever human damage its preservation requires. Too valuable is the residue of the same toxic power dynamic that gave us Schneiderman himself. What would the world look like if, instead of relying on men to advocate on our behalf, we simply put women in their places?

[ad_2]

Source link