[ad_1]

By Susan Haigh, The Associated Press

A detailed account of African-American life in the Northeast during World War II, carefully preserved in the basement of the Connecticut State Library, has been uploaded for a new, modern readership.

Hunched over a lighted magnifying machine, Christine Gauvreau spent months scrolling through reels of microfilm of Black-owned and operated Connecticut newspapers, preparing them to be digitized. They’re some of the latest entrants in the Chronicling America project, a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress to create a national digital database of historically significant U.S. newspapers published between 1690 and 1963.

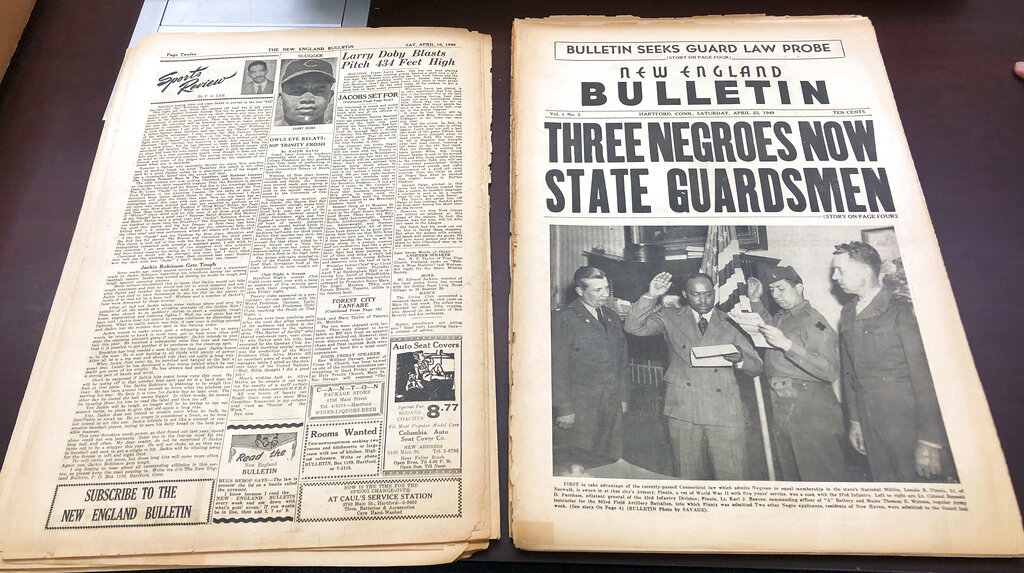

“It’s really a document from the very early civil rights movement in Hartford,” said Gauvreau, who recently finished archiving old issues of the now-defunct Connecticut Chronicle, Hartford Chronicle, Hartford-Springfield Chronicle and New England Bulletin, a family of Black-owned and operated newspapers that began in 1940 and operated consecutively for about a decade.

Connecticut’s latest additions to Chronicling America mark the first African-American newspapers added to the project from a Northeast state.

The four Connecticut-based weekly newspapers upheld a “crusade tradition” of journalism, Gauvreau said. They pushed for the hiring of Hartford’s first Black firefighters and Black bus drivers; advocated for a law barring racial bias in the National Guard; and exposed substandard housing, inferior quality goods and high prices in Harford’s North End neighborhood. In an April 23, 1949 article, the New England Bulletin criticized the “vacillating stand” taken by Connecticut’s State Board of Education, which agreed to allow public high school field trips to “jimcro” Washington D.C. “even though Negro students are segregated” at certain hotels.

In a front page editorial published in May 14, 1949, readers were urged to write to the State Board of Education ask members to “STOP PASSING THE BUCK” and prove “beyond a shadow of a doubt that the board is very much against segregation.” The editorial said the New England Bulletin was taking a stand and criticizing the board for allowing the trips because the decision was “contradictory to the forward-looking policies of the state with regard to any kind of racial injustice.”

An Oct. 5, 1946 column by James E. Shankel, editor of the Hartford Chronicle at the time, wrote about “bare-faced racial discrimination” in Connecticut. He noted a member of a New Haven church had come across a letter from an East Haddam developer advertising lakefront lots for sale and how “this summer colony is restricted to the Caucasian race.”

“Obviously, this advertising letter form was never intended to fall into the hands of prospective Negro buyers,” Shankel wrote.

Other pages of the newspapers provide a window into the culture of the time. Articles cover everything from an Easter sermon at Mount Calvary Baptist Church to performances by musical greats. One advertisement announces a scheduled performance by iconic jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald at the State Theater in Hartford. Written by correspondents stationed throughout the state and region, many articles chronicle the accomplishments of Black residents. One headline announces “City’s Only Army Nurse Returns,” a reference to a Black nurse from Hartford who was honorably discharged from the Army Nursing Corps.

“They wanted to tell the story about what was happening in Black Hartford. They also wanted to highlight issues of discrimination. They wanted to celebrate Black achievement at the same time,” said historian and Professor Stacey K. Close, the associate provost and vice president of equity and diversity at Eastern Connecticut State University. “During World War II, there was a push to improve the employment of African-Americans in terms of the city and the state. And this newspaper took up the challenge.”

There was also an effort by the newspapers to make the readers aware of what was happening elsewhere, especially in the southern states where many still had family members.

“They also made sure that young people knew what was going on in the rest of the country,” Close said.

He added “there was an urgency” to what the newspapers were doing.

“They were trying to push the city to do better than they had done in the past,” he said. “They were an organization and a paper pushing for social, economic and political change.”

[ad_2]

Source link