[ad_1]

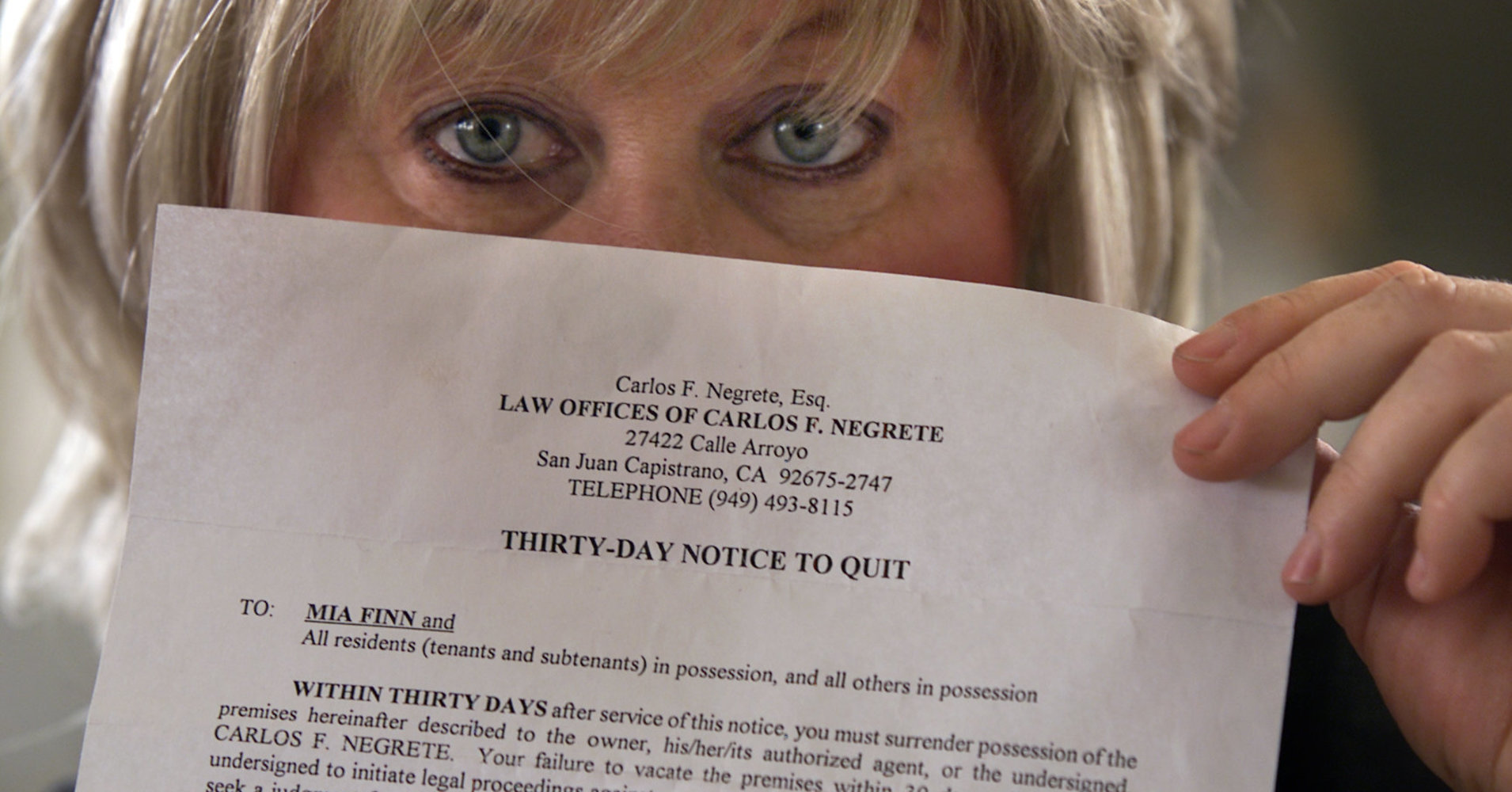

PHILADELPHIA ― The rodent infestation had grown so severe in the home Yazmin Vazquez shared with her nephew that when she left a plate of roast beef on the stove to cool, rats pounced and devoured the entire dish.

The home didn’t have heat and sewage leaked into the basement. By March 2016, the city Department of Licenses and Inspections deemed the property unfit for human habitation. But when Vazquez tried to get her landlord to make repairs, he tried to evict her. Such cases are common in Philadelphia, a city with a high rate of poverty and deteriorating housing. It’s part of the reason why Dan Urevick-Ackelsberg, a lawyer at nonprofit the Public Interest Law Center, took on Vazquez’s case.

“You have a power imbalance between landlords and tenants,” Urevick-Ackelsberg told HuffPost. “It prevents tenants from being able to use laws that are designed to protect them.”

He wanted to “try to flip that imbalance on its head,” Urevick-Ackelsberg said, by representing low-income clients, like Vazquez, who are often intimidated by their landlords.

Vazquez sued her landlord and property manager, and ultimately settled. As part of the agreement, the landlord and property manager agreed to abide by preconditions that allow for collecting rent.

John Moore via Getty Images

Vazquez is one of many Americans who have been caught up in the eviction crisis ― the magnitude of which has only recently come to light thanks to Eviction Lab, a data initiative led by Matthew Desmond, Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvard sociologist. Desmond is the author of Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, which took an intimate look into how families in Milwaukee fared after getting kicked out of their homes.

In 2016, 2.3 million evictions were filed in the U.S. These cases disproportionately affect low-income women, particularly women of color, victims of domestic violence and families with children, according to the lab. These numbers likely don’t even tell the entire story though, since so many struggling residents live in unregulated housing, where there may just be a verbal lease agreement and tenants can be kicked out without much notice.

Desmond’s findings underscore the need for more affordable and habitable housing. They also highlight the need for legal reforms that would give underserved renters a shot at remaining in their residences, or at least at negotiating agreements that work for them.

Armed with a better understanding of the sheer scale of the eviction crisis, a handful of cities are now working to better protect low-income tenants. In Philadelphia, where one in 14 renters faces an eviction filing, that means finding more affordable housing options, educating tenants about their rights and offering more legal representation for low-income renters.

“We know, by and large, tenants who are represented have better outcomes,” said Rasheedah Phillips, managing attorney in the housing unit of Philadelphia’s Community Legal Services.

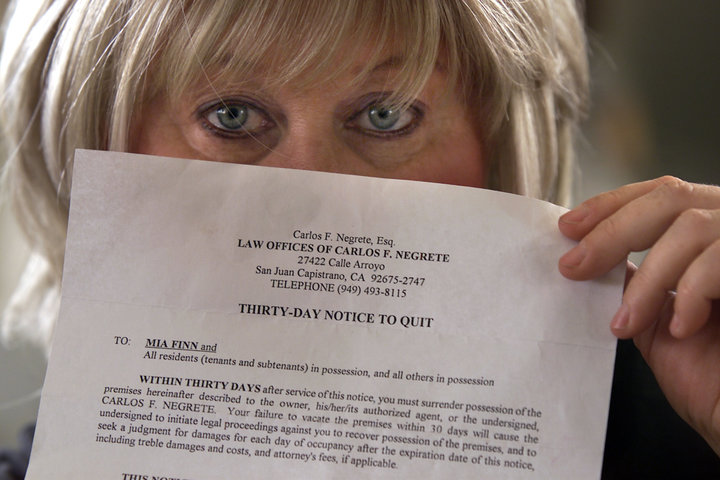

Irfan Khan via Getty Images

In addition to demonstrating the scope of the issue, Desmond’s book also showed that eviction isn’t just a byproduct of poverty, but is actually fueling the cycle. That’s of particular concern in Philadelphia, which remains the poorest major city in the U.S. More than a quarter of residents live below the poverty line.

In the worst cases, tenants end up homeless. That is traumatizing for the resident and taxing for the city, as one shelter bed in Philadelphia costs about $15,000 a year, according to Liz Hersh, director of the Office of Homeless Services in Philadelphia.

Even if a tenant doesn’t end up on the streets, there are still other devastating consequences. Eviction judgments can come with hefty fines, which can increase a person’s already existing debt load, and future landlords are less likely to rent to someone who’s experienced eviction.

For children, eviction is particularly punishing, since it could mean abruptly switching schools or being taken away from their families, said Philadelphia City Councilwoman Helen Gym.

“Where you are evicted, usually it’s a spiraling downward,” Gym said. “There are very serious consequences.”

The major contributing factor to evictions is a lack of affordable housing. A 2016 report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition found that there are no states in which a worker earning minimum wage can afford a modest two-bedroom apartment. That same year, 25 percent of renters spent more than half their income on housing costs, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Compounding the issue is the fact that many low-income tenants aren’t aware of their rights, can’t access legal counsel or end up in court just for demanding that their landlords make basic improvements to their homes.

More cities are developing programs and passing legislation to help improve outcomes for renters. New York City, which has the most evictions of any major U.S. city, passed a law last year that guarantees legal representation to any low-income resident facing eviction. In more than 90 percent of eviction cases in New York City, landlords had access to legal representation, and 90 percent of tenants didn’t. It was the first law of its kind in the U.S.

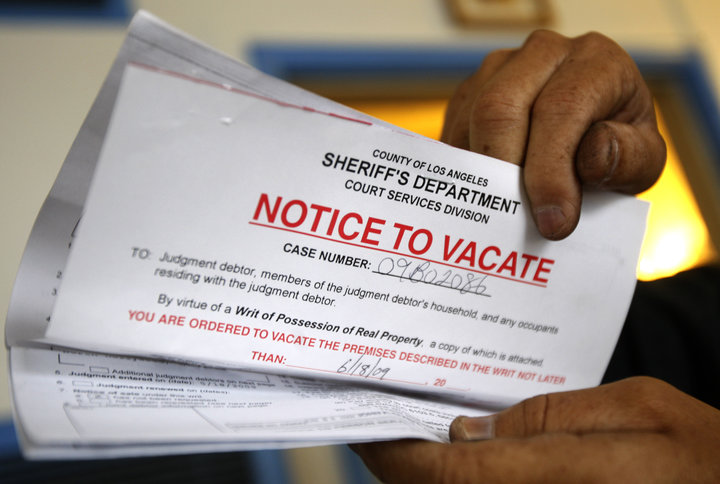

Lucy Nicholson / Reuters

Just this week, San Francisco voted in favor of a measure that would provide a lawyer to any tenant facing eviction.

Philadelphia hasn’t followed that route, but advocates have implemented new policies to help support the needs of low-income renters.

In January, the city launched the Philadelphia Eviction Prevention Project, which offers a helpline for tenants in need, connections to legal services and information for at-risk tenants. In its first three months, the program provided 220 tenants with advice, referrals or full legal representation, according to Phillips.

It’s a big step considering that tenants are typically poorly represented. In Philadelphia, 85 percent of landlords have lawyers in eviction cases, whereas about 5 to 8 percent of tenants do, Phillips said.

Landlords now also have to prove that they have a license to rent and that their buildings are up to code in order to move forward with an eviction.

Last year, the city secured $500,000 to support anti-eviction measures. It pales in comparison to the amount of funding New York City secured, but Councilwoman Gym said it’s a start and she hopes to expand those efforts. That funding allowed three agencies that represent low-income tenants to hire five full-time lawyers, and one part-time lawyer.

In April, Philadelphia’s eviction task force released an extensive report, outlining recommendations to help prevent evictions. Those recommendations included launching a public education campaign on the topic and giving low-interest loans to landlords who own just a few properties, in order for them to be able to improve aging units.

While the task force suggested increasing the number of lawyers available for low-income tenants, it didn’t recommend passing a right to counsel law. Many housing advocates say funding first needs to be put toward making more affordable housing units available in a city where there’s only one unit available for every 17 extremely low-income renters.

“You have to start with the premise that having safe home with a roof over your head is a basic human right,” Urevick-Ackelsberg said. “When you’re comfortable with people living in horrific conditions, spending 70 percent of income on their home, you’re always going to have this problem.”

[ad_2]

Source link