[ad_1]

Four-time Tony Award nominee Celia Keenan-Bolger grew up idolizing Scout Finch, the overall-clad rebel at the center of Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and now, as a grown-up, she’s finally getting to play her.

At an early workshop for the play, adapted for the stage by “West Wing” creator Aaron Sorkin, Keenan-Bolger, 41, was brought on as a stand-in to read as Scout before an age-appropriate actor would eventually assume the role.

But Keenan-Bolger, who made her Broadway debut as an aspiring sixth-grade spelling bee champion in “The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee,” understood how slight but effective modifications to her voice, posture and demeanor could bring out her inner child. By the end of the reading, everybody was convinced a change was in order.

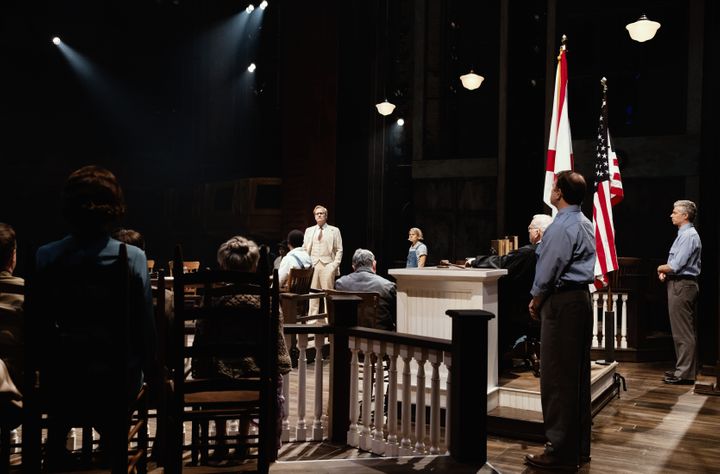

And so the play’s central trio of children, who narrate the well-worn story, is now portrayed by adult actors in the production currently running at the Shubert Theater.

For Keenan-Bolger, the role is a culmination of dual lifelong passions for theater and social justice, an intersection she doubted would ever manifest so perfectly onstage. Having grown up in a politically active family, she says the book was a de facto “manual” in her home, embedding important lessons about race and history in her psyche. But like many adults revisiting the story with fresh and decidedly more critical eyes, she also questioned the limitations of “To Kill a Mockingbird” and its continued relevance to audiences today. (The play includes notable departures from the source material, particularly in its handling of black characters.)

“It cannot be the be-all, end-all race manual right now,” Keenan-Bolger said.

With a handful of key precursor trophies in her pocket, Keenan-Bolger is the front-runner to take home the Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play on Sunday night. Ahead of the ceremony, we caught up with the actress to talk about her lasting connections to the novel, how playing Scout has deepened her own activism, and why young people deserve a new definitive text about race.

I have a list of people who I feel like are criminally overdue for a Tony win and you are top three. What does it feel like to be nominated this time around?

I feel especially lucky to be included because I can’t remember a better season of new plays on Broadway with so many extraordinary artists. I feel like the version of myself I want to be is like, “Who knows? We’ll see how it goes!” But, of course, I would really love to win. It would be wonderful for the play and just really meaningful to me.

When in your life did “To Kill a Mockingbird” first reach you, and was it a formative text at that time?

My mother read it to me before I could even read chapter books. When I was young, it became this manual in our home. We watched the movie and I remember it inspired a lot of conversations about race and segregation. It was a space my parents used not just to talk about politics and social justice in our country, but also standing up for what you believe in and standing on the right side of history. That was very indicative of the house that I was raised in. My parents were just really wonderful fighters for social justice, and there’s a legacy of that in my family. They would’ve never said use your privilege at the time, but it’s what they meant. Because I’m white, I’m going to end up in situations where I need to be the person that stands up for someone who has less than me.

Scout Finch became this hero, especially to young women, for the ways she calls out injustices and challenges norms of gender. Who was she to you when you first came across her?

Any little girl who has felt a little bit of an other is immediately going to relate to her. She was so strong and unafraid in a way that I felt like I wanted to be, while also having this amazing sense of humor. It probably was how Harper Lee felt growing up in Monroeville, Alabama, because who she was expected to be and who she was actually felt so at odds. I grew up in urban Detroit, Michigan, and had no real ties to rural Alabama, and yet I felt so tied to her. I was always navigating this feeling of otherness for all of my public school education because I was one of the only white kids at my school. It’s amazing to me how many different women I’ve met for whom Scout Finch was important for the same and other reasons.

You’ve convincingly played children onstage before (side note: “The I Love You Song” from the “25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee” is in my top 25 most played). How did your approach to Scout differ from those roles?

Between Aaron Sorkin and Harper Lee, they gave me a really good launchpad. Even though I’ve played so many people younger than myself, they’ve all been really different, especially this character because of the time period and location. The accent also really helped me locate who Scout was. Before we started rehearsal, I made a trip down to Monroeville, where Harper Lee was born, and honestly all I wanted to do was talk to people and secretly record their voices. I was like, “How do I not sound like a New York actor doing a Southern accent?”

With the political dumpster fire raging around us, were you seeking out work that engaged directly with politics and social justice?

I feel like the dream in my life is to get to do a really good play that has cultural relevance, and that has certainly never been more true than right now. I always assumed it would only exist off, off, off Broadway. I don’t know if you told me it was going to be this enormous commercial hit on Broadway, I would’ve believed you. But that makes it so much more meaningful, because we are reaching so many people from different backgrounds, like all these tourists from the South who’ve never necessarily seen a Broadway show but really loved the book, or all the lawyers who feel a kinship to Atticus Finch. Politicians, school groups, everybody!

That’s so important, because I feel like there’s a reality that this play is preaching to the choir in some ways, given how mostly white, liberal audiences are seeking out this story.

We’ve been doing student matinees for New York City public school kids and they have such different responses. As soon as Atticus begins his cross-examination, without fail there’s an audible, “Ooooooh.” No adult audience has ever done that. They are listening and actually receiving this information.

In the second act, there’s a line Calpurnia has when we find out that Tom Robinson is dead. After Atticus wonders why he would run from the guards, she says, “Or why a prison guard would shoot a one-armed man climbing a fence.” The students erupted in applause. I was like, yeah, because they actually have to engage with the idea that when they come into contact with the police they are scared for their lives. I appreciate in some ways there’s sort of a rallying cry to white liberals that the play is trying to message, but I do think the characters of Calpurnia and Tom Robinson have a very different place in the play when we do it for the student matinees.

There’s been this demythologizing of these characters and a reexamination of the text in recent years given some of the creakier parts of the novel. What did you take away from the book when you revisited it as an adult?

When I reread it again before we started rehearsals, I was struck at this notion of justice and how it’s extended to Boo Radley, but most certainly not to Tom Robinson. That never really resonated with me before, but now I’m like of course the white guy gets to be spared, but Tom Robinson is lying dead in prison and his family has to go on. When Harper Lee wrote the book in 1960, it was so radical, and what she was doing was so beyond what most authors were writing about race at that time. In a beautiful way, it’s an enduring story. I have a 4-year-old myself and I’m so interested in what his experience of reading the book will be.

The book has become a fixture of middle school reading lists and somewhat problematically the definitive text about race for that age group. Do you think it’s still important to teach to kids today?

I do, but it can only be taught unless there’s a work that accompanies it where the black characters are the protagonists as opposed to the white people’s experience of the black characters. When I read it, the next book we read was “Native Son” by Richard Wright. “To Kill a Mockingbird” has to be accompanied by a book that’s written by an African American and the characters are not expressed through a white gaze. But I do think that the book is very special, especially if you give it context. It was written in 1960 about 1934, and you have to ask how does it hold up in 2019? What can we take away here? As far as a manual about how we should be, it cannot be the be-all, end-all race manual right now.

Do you feel like the play has strengthened your activism, or is it more difficult to engage with these issues outside of the theater given you spend so much time with this heavy material onstage?

To bury my head in the sand is its own kind of privilege. I’m able to do that because I’m in a position where that’s even possible. I can’t totally disengage because then I can’t really do my job. I think we all have experienced varying levels of burnout where we just can’t engage this week or month because we’re just fatigued. In some ways, the discipline of doing this show over and over again, continuing to turn over these questions and being required to engage makes me feel grateful even when I don’t necessarily want to do it.

Your co-star Jeff Daniels has described the play’s impact as “punching white America” in the face? How has the play made you see your own whiteness and privilege and has it raised new questions about how you move through the world?

I have a different relationship with my whiteness than a lot of people because I was a minority in so many spaces growing up. Then I went to college and I remember thinking, “What’s with all the white people?” My life in New York feels much more white than I wish it was. The theater has a long way to go, and I hope that at least from an artistic point of view that I will get to be in more spaces where the stories that are being told are not just written by people who look like me. It’s happening, but as Calpurnia says in the play, “Morning is taking it’s sweet time getting here.” It’s a slow process.

In the play, Scout is battling between taking her father’s advice of being civil to even the most despicable people and unapologetically calling out injustice. Where do you fall in your own life?

I’m a combination of Atticus and Calpurnia. Because of the nature of my family, I’m always going to lean more on the side of radical empathy. I sort of believe Atticus’ idea that there’s goodness in everyone, but I also understand that it’s not enough. You can say there’s goodness, but there has to be action that accompanies the empathy. Sometimes my liberal friends will say things [about Trump voters] like, “They are ignorant! They have to be left behind! There’s no saving them!” I’m not sure I’m ready to write off people who I don’t agree with, but I also don’t think saying we just have to give them time is also enough. We have to approach it from a place that is somewhat generous, but also holds all of us to a standard of being better.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link