[ad_1]

Brendan Fernandes, Ballet Kink, 2019, performance view at Guggenheim Museum, New York. From left to right, the performers are Abigail H. Simon, Allison Walsh, Tyler Zydel, Elina Miettinen, Josep Maria Monreal Vidal, and Violetta Komyshan.

COURTESY THE ARTIST, GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, AND MONIQUE MELOCHE GALLERY, CHICAGO/SCOTT RUDD EVENTS

‘Ballet is my kink,” Brendan Fernandes likes to say. Fernandes is a trained ballet dancer, and for him, the centuries-old dance form offers rules to be challenged, boundaries to be crossed, and power dynamics—charged with pleasure and pain—to be emphasized. He has spent nearly a decade exploring the visual language and politics of ballet through choreographies of endurance executed by professional dancers, and now he has brought one of his most ambitious projects to date to this year’s Whitney Biennial.

At the Whitney Museum in New York, Fernandes is showing The Master and Form (2019), an installation composed of a steel cage of black scaffolding standing beside a trio of beam sculptures, all designed in collaboration with Norman Kelley Architects. On most days, the work resembles a riff on Minimalist sculpture from the 1960s. But come on a Friday or the weekend, and you might catch a troupe of ballet dancers animating the work, using the bars to stretch and support their bodies. (The performers at the Whitney are Allison Walsh, Amy Saunder, Charles Gowin, Héctor Cerna, Jennifer Whalen, Josep Maria Monreal Vidal, Mauricio Vera, Tiffany Mangulabnan, Tyler Zydel, and Violetta Komyshan.) If performed well, ballet appears effortless, but Fernandes destroys that notion, underscoring the discipline involved in enacting elegant gestures—how, for example, even in stillness, there is invisible and intense exertion involved.

Playing the role of ballet master, Fernandes asks his dancers to carry out acts of endurance and other set tasks during each hour-long performance. They hold arabesques, swan dives, splits, and other classical positions, with each shift determined by a timekeeper—a gallery assistant—who snaps their fingers. But, in a departure from standard ballet etiquette, Fernandes also releases them to freely create their own choreography at times—dancers are given two 10-minute-long improvisation sessions during the performance.

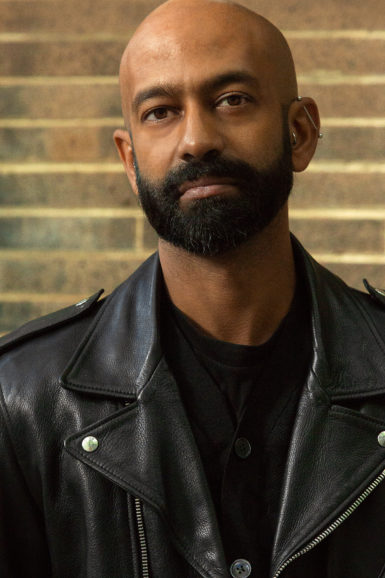

Brendan Fernandes.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MONIQUE MELOCHE GALLERY, CHICAGO/MILO BOSH

“I am questioning not only the mastery of the body’s technique, but also the mastery and authority of yourself within the space,” Fernandes told me on a recent afternoon in Chicago, where he is based. “The dancers are always given the agency to leave, sit down, or break from the performance mode, and look after themselves.”

Fernandes and I met at the Graham Foundation, where he originally conceived The Master and Form during a six-month residency in 2017. The foundation’s building is a 20th-century Prairie-style mansion, and for the performance’s original iteration, he had instructed dancers from the Joffrey Academy of Dance to move through its expansive rooms and up and down its grand staircase. The Whitney’s fifth floor is an entirely different setting, filled with airy galleries and scenic views of the High Line, and Fernandes wanted to challenge its open architecture by creating what he describes as “a new playground, with devices that create patterns to move through.” When performers aren’t present, the area remains a site to contemplate movement. Recorded thuds of footsteps fill the space, in what can often sound like the haunting residue of human bodies moving through the gallery.

Fernandes no longer dances ballet, but when he did, he would use a stretcher designed to manipulate the anatomy of his feet to enhance his arches. Inspired by these devices, the three beam sculptures are built to assist dancers, all the while demanding that they struggle to reach an established notion of perfection. It’s not a coincidence that they resemble BDSM furniture. “There’s a wickedness or an austereness to them,” Fernandes said. “They support, but they are also a burden. There’s pain and pleasure.”

This perverse form of ballet works toward what Fernandes describes as a “queering of space,” challenging the conventions of a dance stage and engaging the idea of a social environment that defies definition. The boundaries of the performance are porous: there’s an open, though not explicit, invitation for audience members to participate; anyone is welcome to walk around or up to dancers and express themselves via movement. “When we enter a space like the museum, we’ve been told how to move,” he said. “There’s an inherent choreography, and we can uphold it or challenge it.”

Brendan Fernandes, In Second, 2018, performance view featuring Andrea De León.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MONIQUE MELOCHE GALLERY, CHICAGO/RCH

It’s been a busy a year for Fernandes. In addition to his work in the Whitney Biennial, he opened a solo exhibition at the Noguchi Museum in Queens earlier this month, and he will stage a new performance there in September. He also has a five-month project, Call and Response, opening at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in June. This, too, will involve a dance-based installation of black scaffolding; during “open rehearsals,” museum visitors will be able to enter the space and respond to prompts such as “hide in the landscape” or “make eye contact.”

The Whitney Biennial has been the subject of scrutiny, thanks to a wave of protests at the museum against Warren B. Kanders, the vice chair of its board, led by the activist group Decolonize This Place. Kanders owns Safariland, a defense manufacturing company whose tear gas canisters have been used to attack asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border, and protestors have called for his removal. (Kanders has said that he is “not the problem” that the protesters should focus on.) In April, nearly 50 Whitney Biennial artists, including Fernandes, signed an open letter supporting the calls for his resignation.

Fernandes is friends with Michael Rakowitz, the only artist who chose to withdraw from the exhibition after the Kanders controversy emerged. (The artists teach together at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.) Fernandes said he also contemplated pulling his work from the show, but then he decided that doing so would be a form of inaction.

“I want to work within the system and the institution to create a powerful statement through performance,” he said. His practice is built on collaboration, so he added that, if he pulled out from the Biennial, he’d be dishonoring his dancers’ work—all those hours of practice they put into developing the piece. “We’d be forgetting, erasing those labors,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link