The mobile barriers known as Mose have already been closed 50 times since 2020

Maybe there is hope after all that Venice will survive into the next century. On 1 June, for the first time ever, at a conference organised by the new Fondazione Venezia Capitale Mondiale della Sostenibilità/ Venice Sustainability Foundation (VSF), politicians (well, ex-politicians, but major public figures nonetheless) admitted that sea-level rise is the main problem facing the city now.

Hitherto, the dozens of conferences held in Venice since 2000 have tended to be of two sorts: scientists speaking to other scientists, often about the coming disaster, but totally ignored by the authorities; and symposia on the social, economic and cultural aspects of the city, now and tomorrow, totally ignoring the fact that Venice will have no tomorrow unless steps are taken to prevent its inescapable attrition by the rising water level.

This conference, entitled “Mose and the others: international defences against flooding” and orchestrated by Pierpaolo Campostrini, the director general of Corila, the scientific body co-ordinating research into the Venice lagoon, was opened by Renato Brunetta, the minister of public administration in the governments of both Silvio Berlusconi and Mario Draghi, and chairman of VSF.

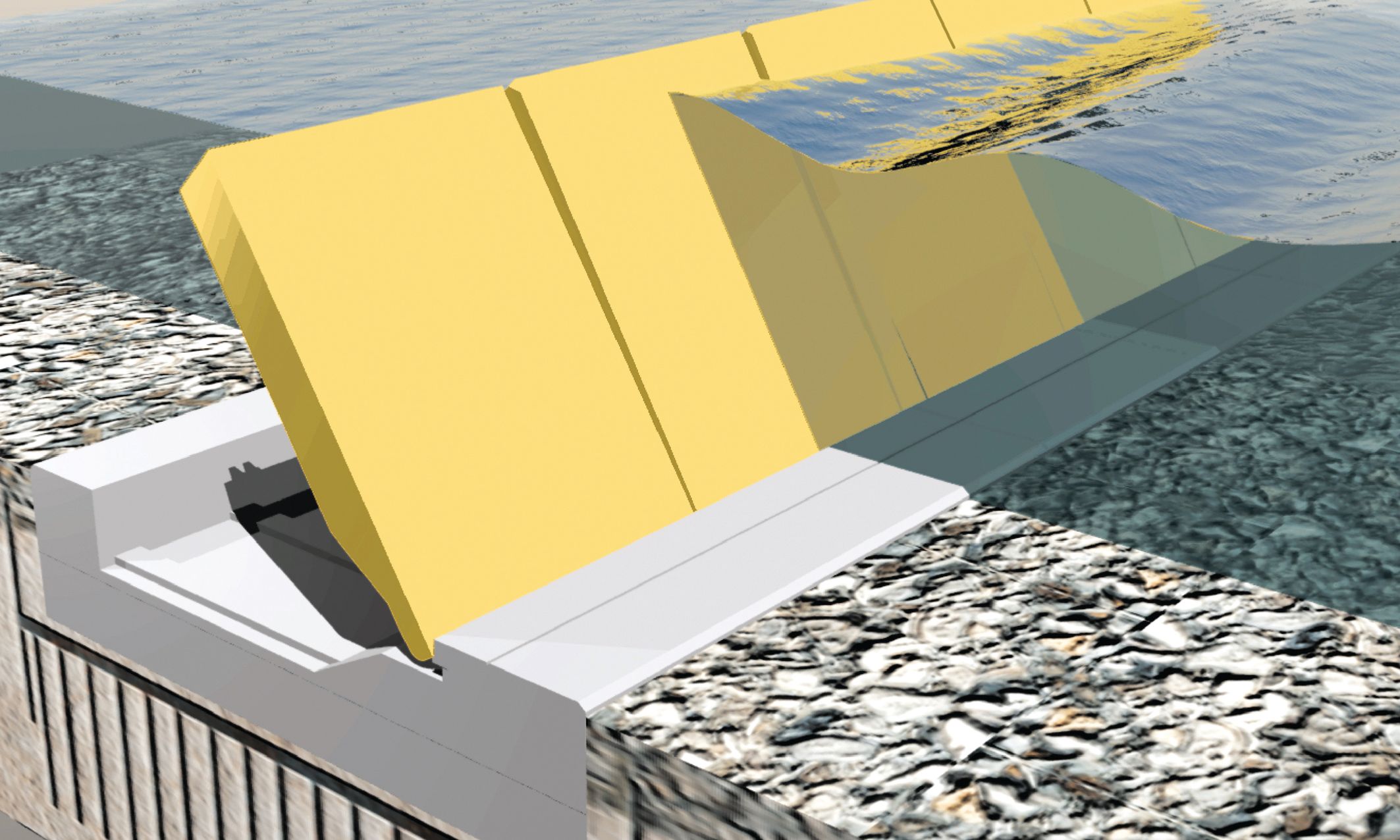

He celebrated the successful completion of the mobile barriers known as Mose, which have already been closed 50 times against flooding since 2020. This vast project, bitterly opposed in the 1990s by the Left and Green parties and highly politicised, has taken 17 years to become operational and cost €6.5bn, of which possibly as much as half a billion euros was due to corruption that poisoned relations with central government and the Venetians.

Most dangerously, it led to the suppression of the truth that Mose is the means of protecting the city against temporary flooding events but not the chronically rising sea level. This goes some way towards explaining why it is not on the to-do list of any Italian politicians, national or local.

The first step therefore has had to be to exorcise Mose’s evil reputation and make everyone feel good about having at last stopped the flooding. This was the message of both Brunetta and the closing speaker, Costa, a former minister of public works, EU Commissioner for transport, and mayor of Venice, who told the audience that Italy should be proud of it: Mose should be added to the list of Unesco World Heritage monuments, he said; its know-how should be offered free to the world at COP28 in Dubai. The flooding specialists present from the UK, The Netherlands and Galveston, Texas praised Mose and described what their own equivalents were, the implicit message being that Mose is now a full member of the flood-barrier club.

Then Costa made his two radically new statements. The first was that the barriers should be closed “as often as it takes” to stop the Venetians ever getting wet, thereby cutting right across the current practice, which is to close them only when the water is expected to reach 130cm or more above the reference point established in 1897, by which time important parts of the city are under water, especially St Mark’s basilica, which is having to adopt separate measures to protect itself. This apparently perverse policy is to allow ships easy access to the commercial port of Marghera inside the lagoon, a point emphasised earlier that morning by Mayor Luigi Brugnaro.

Costa’s solution to these conflicting needs was to suggest a holding port outside the entrance to the lagoon, although he did not go into more detail. Instead, he moved on to his second surprise. We are in the stage of “after-Mose”; by 2100 “Venice may disappear by crumbling away”, he said. Speaking to The Art Newspaper, he said, “Now we need to come up with a new idea for the sake of our grandchildren and the centuries ahead.”

But whose job it is to come up with that new idea is still unclear. After the meeting, Campostrini told The Art Newspaper that the most urgent step now is for the government to appoint a head of the still unconstituted Autorità per la Laguna di Venezia, decreed back in 2020 to take charge of strategic planning for the future. He added that Mose also needs funding for its maintenance and operations, and is bedevilled by a lack of engineering skills due to the bankruptcy of some of the firms that built it.

It remains to be seen, therefore, whether the plain speaking at the 1 June meeting will lead to action in Rome. If not, the slogan of VSF, “The oldest city of the future”, risks being just a neat turn of phrase.