[ad_1]

The entrance to Unlimited.

PHOTOS: ANDREW RUSSETH/ARTNEWS

It’s not exactly a secret that super-size artworks have proliferated in recent decades, and especially in the last few years, but nothing drives home the point quite as dramatically as a visit to Unlimited, the Art Basel fair’s section for pieces that do not fit in fair booths—or even most galleries. Soon, some of the works in the section will no doubt find their way to exhibition halls that once were industrial warehouses or power stations, or were designed from the start with bigness in mind. For now, they are here in Basel, through Sunday.

However, it’s important to say that not everything in Unlimited is gargantuan. It is also a place for what amounts to focused, full-on gallery exhibitions—like a sprawling array of great material dating from 1971 to 1974 by the shapeshifting feminist Martha Wilson and a full collection of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s 1987–92 puzzle works—plus video works that require a nice, large, dark room to enjoy to their fullest—like Jacolby Satterwhite’s latest stunner, Birds in Paradise (2019), or the Bruce Conner classic REPORT (1963–67).

Below, a look of some of what is on view in Unlimited, through numbers.

Franz West, Test, 1994.

75: The total number of works included in Unlimited, up from 72 last year.

7: The number of times that Gianni Jetzer, curator-at-large for the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., has organized Unlimited. This is his final edition.

28: The number of little couches in Franz West’s Test (1994), all of them with slipcovers by Gilbert Bretterbauer. The many people sitting on them are, strictly speaking, not part of the work. (The piece provides one of the few places to sit down in Unlimited.)

Joan Semmel’s Skin in the Game (2019).

24: The width, in feet, of Joan Semmel’s 2019 painting Skin in the Game (a good name for a work at an art fair). The riotously colored four-panel work presents five nude self-portraits from various angles.

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled, 2000.

35: The number of military blankets that make up a disturbing untitled Jannis Kounellis installation from 2000. It also includes 13 military hospital beds and 30 hunks of steels, some of which are wrapped around themselves so that they resemble bodies.

Daniel Knorr, Laundry, 2019.

5: The number of minutes, roughly, I spent watching canvas cars being theatrically splattered with paint for Daniel Knorr’s performance-sculpture-painting-installation Laundry (2019). Really something!

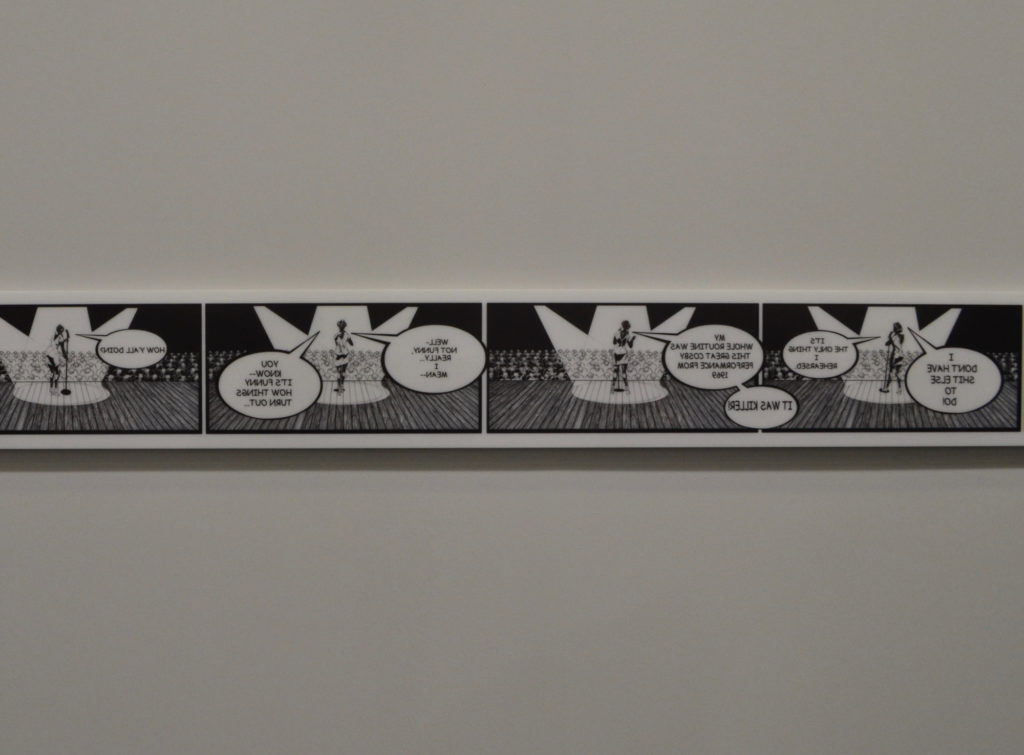

Detail of Kerry James Marshall, RYTHM MASTR Daily Strip, 2018.

695.7: The length, in inches, of Kerry James Marshall’s RYTHM MASTR Daily Strip (2018), which brings together the three main series in the comic that he began making in 1999. The work presents life in the Bronzeville section of Chicago’s South Side with some poignant, surreal flourishes.

The line to enter Abdulnasser Gharem’s The Safe (2019).

40: The approximate number of seconds that visitors are allowed inside Riyadh-based artist Abdulnasser Gharem’s The Safe (2019), a padded cell in which one can stamp the walls with politically charged phrases in English and Arabic, like “Violence is its own demise.” Also inside is a reversed depiction of the Saudi Arabian flag—the work is a response to the Saudi government’s murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi last October at its embassy in Istanbul.

Steven Parrino, 13 Shattered Panels (for Joey Ramone), 2001.

13: The total number of gypsum plaster boards painted with black industrial lacquer and violently broken apart for Steven Parrino’s straightforwardly titled 13 Shattered Panels (for Joey Ramone), 2001. It’s presented by Gagosian. (If you are in New York by July 15, more Parrino can be found at Skarstedt’s new space on the Upper East Side.)

Pae White’s foreverago, 2017.

128: The width in feet of Pae White’s unrelenting tapestry foreverago (2017). It’s the largest work she has ever made in the medium.

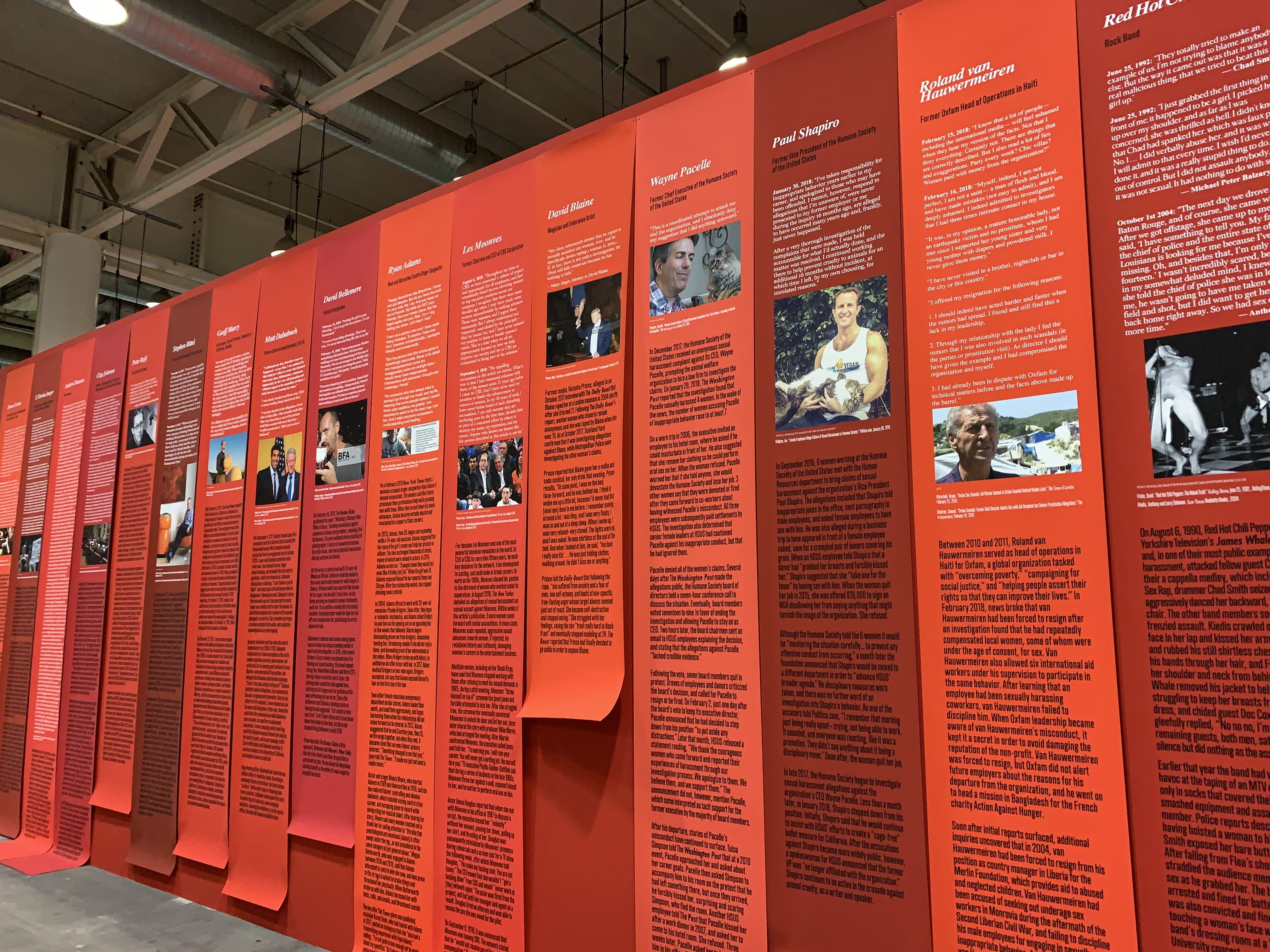

Installation view of Andrea Bowers, Open Secret, 2018.

200: The approximate number of panels in Andrea Bowers’s Open Secret, one each for a man accused of harassment or inappropriate behavior or violence as part of the #MeToo movement. Following opening day, Bowers removed a panel and apologized after a survivor who was pictured on it said that she had not consented to being depicted and called for it to be taken down.

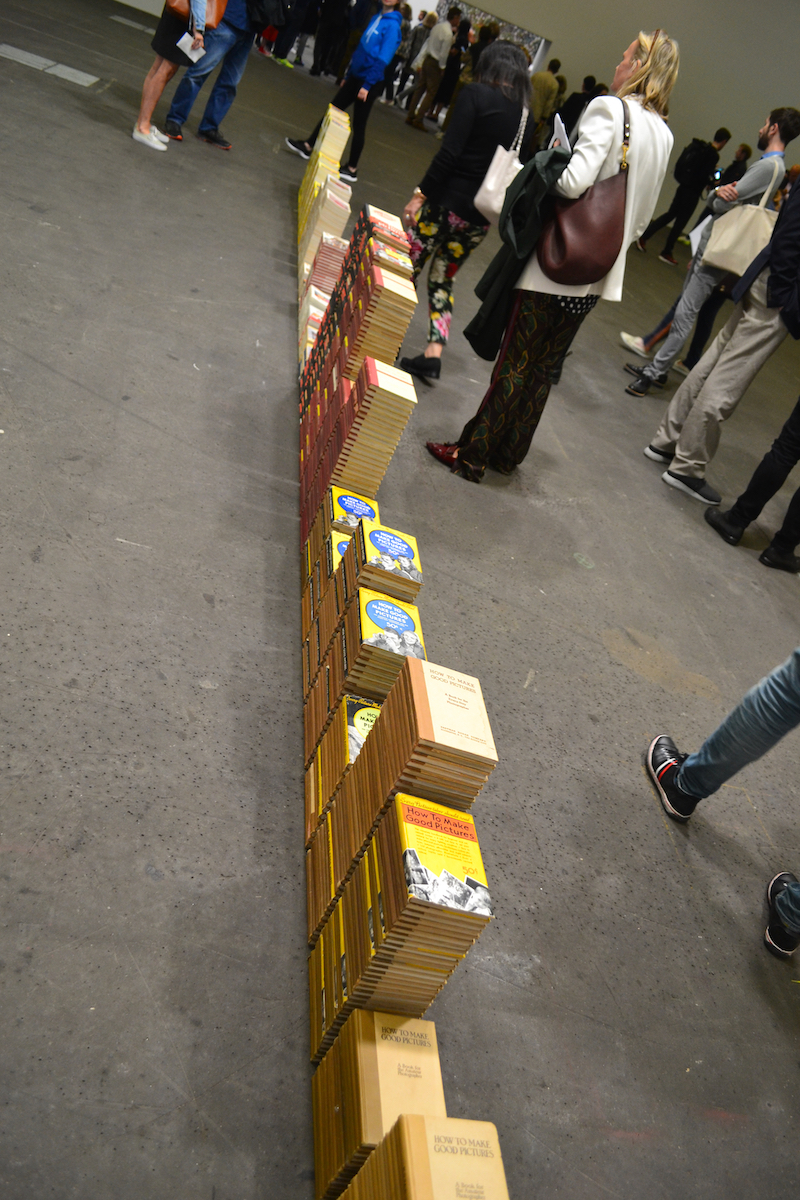

Zoe Leonard, How to Take Good Pictures, 2018.

1,033: The number of copies of How to Make Good Pictures—in various editions—that are stacked and arrayed in a long row for Zoe Leonard’s 2018 piece How to Take Good Pictures (to which the classic how-to book was later renamed).

Mircea Cantor, Aquila Non Capit Muscas, 2018.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MAGAZZINO, ROME

220: Length, in seconds, of Mircea Cantor’s video Aquila Non Capit Muscas (2018), which shows an eagle repeatedly ripping a drone out of the sky. It is quite satisfying to watch—visceral and also politically loaded.

7: The total number of copies that exist of Cantor’s eagle/drone work.

Partial view of Akram Zaatari’s The End of Love, 2013.

150: The number of photos of wedding couples (plus a few solo portraits) that make up The End of Love (2013), a piece by Akram Zaatari of the Arab Image Foundation, which uses images shot in the Beirut studio of Hashem El Madani.

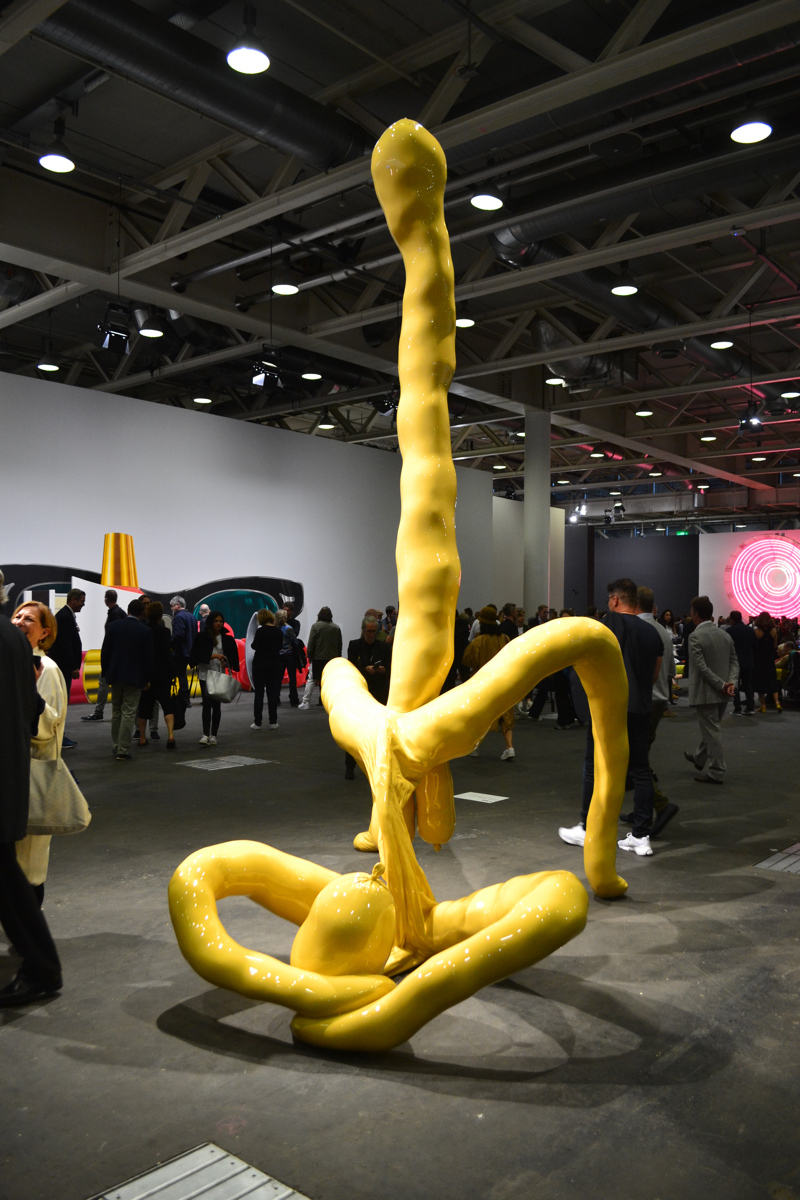

Sarah Lucas, Champagne Maradona, 2015. (Two versions, in two slightly different shades of yellow, were part of the artist’s show in the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015.)

15: The height, in feet, of Sarah Lucas’s 2015 sculpture Champagne Maradona, in which a giant phallic figure shoots dramatically—but also a bit awkwardly—toward the sky.

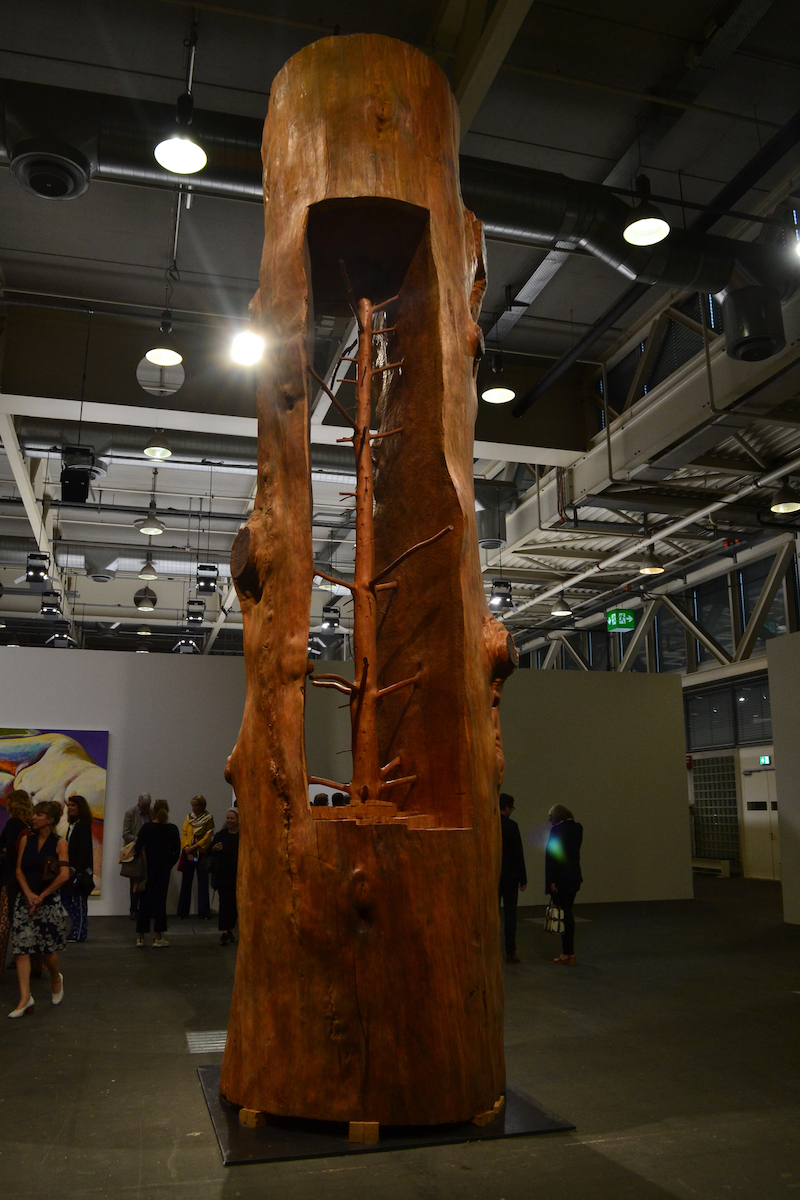

Giuseppe Penone, Cedro di Versailles, 2000–03.

20.7: The height, in feet, of Giuseppe Penone’s sculpture Cedro di Versailles (2000–03), which was carved from a cedar tree destroyed by storms at the former French royal residence in 1999.

194: The estimated age of the tree used in Penone’s piece, meaning that it was planted around 1805, when Napoleon was at the start of his reign as the Emperor of France.

Huma Bhabha, We Come In Peace, 2018.

13.7: The height, in feet, of Huma Bhabha’s bronze piece We Come in Piece (2018), which stood atop the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York last summer.

Valentin Carron, DUST MINT, 2018.

21: The height, in feet, of Valentin Carron’s DUST MINT (2018), a stack of 30 aluminum versions of classic wooden apple crates.

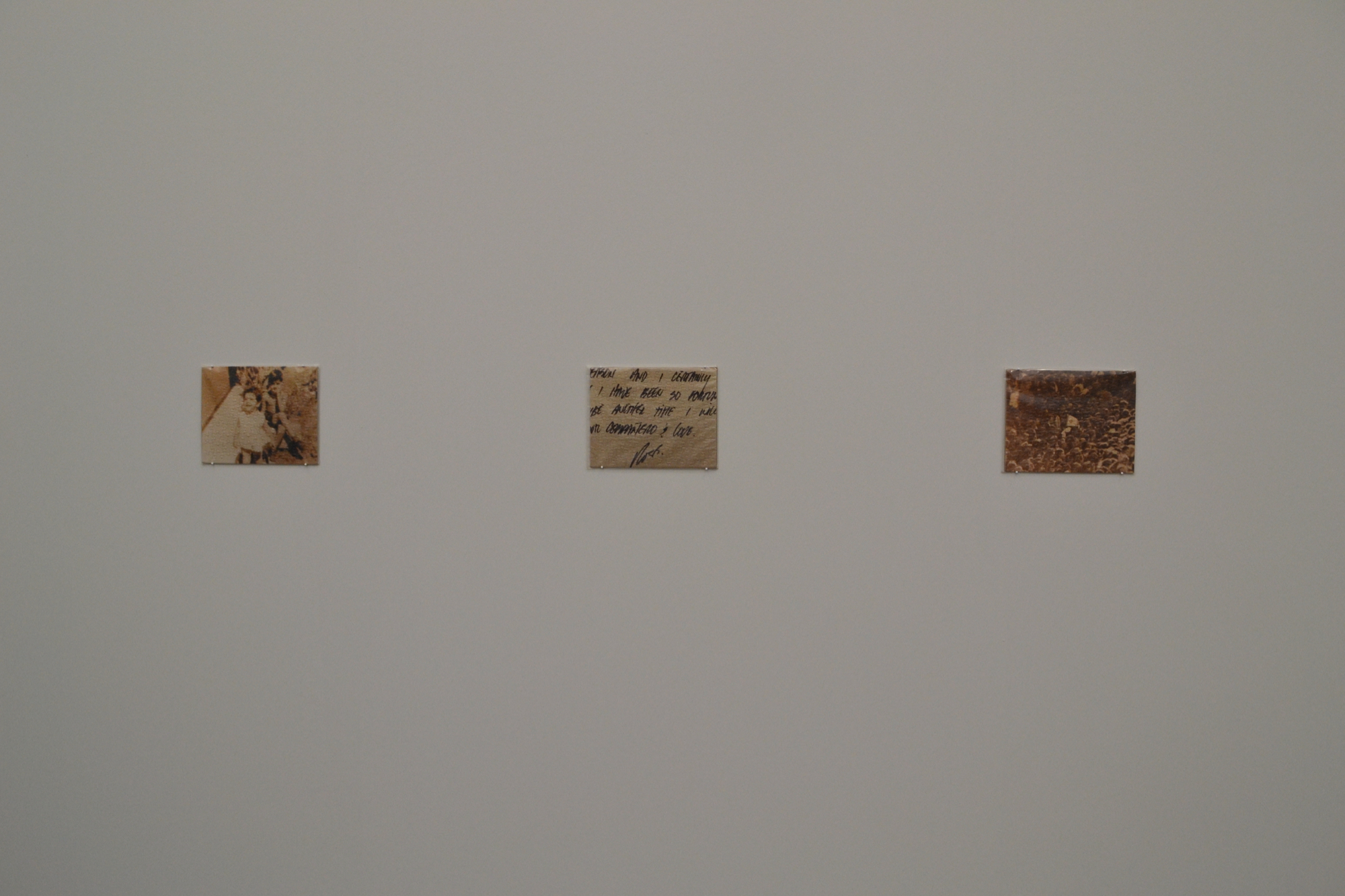

Three pieces from a complete set of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s untitled puzzles, 1987–1992.

55: The total number of puzzles that Felix Gonzalez-Torres made with photographs, which are being shown as a complete set for the first time since they were made from 1987 to 1992. The presentation is one of the most poignant, beautiful artworks on view in Basel this week. Let’s hope a museum ends up with it.

[ad_2]

Source link