[ad_1]

A naked woman, rendered in rickety black-and-white strokes, stares with a mix of fascination and horror at a zit just below her nipple. She gives it a squeeze, and it erupts with a mushroom cloud of pus.

“My body is an endless source of entertainment!” she says to herself.

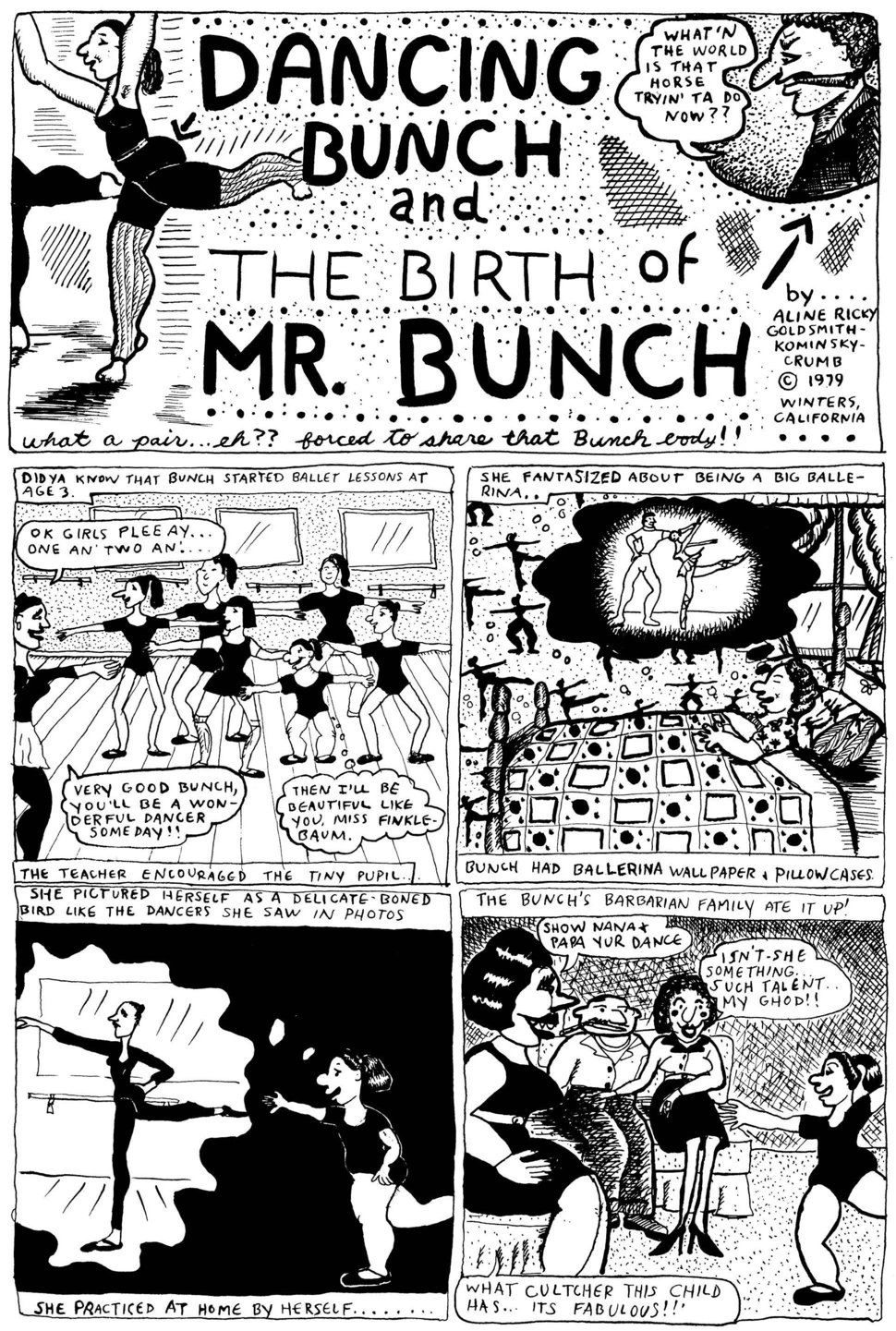

The naked woman is the Bunch, the avatar of groundbreaking comic artist Aline Kominsky-Crumb. She uses the Bunch, created in the 1970s, to tell the unsanitized, mundane and utterly grotesque story of her now 69-year-long life ― the first autobiographical comic by a woman. Tackling topics like binge-eating and masturbation, plastic surgery and rape, her narratives act like a magnifying mirror that sharpens the contours of a juicy pimple, sparing no dirty detail.

Nearly three decades after Kominsky-Crumb’s “Love That Bunch” was originally published in 1990, Drawn and Quarterly is rereleasing the comic compendium (with additional artwork created from 1976 to 2014) this month. The book traces how a horny Jewish girl growing up in the suburbs of Long Island in New York became underground comics royalty, a fearless truth teller with a penchant for exaggerating the ugliest bits.

“I thought I’d bring out the worst part of myself and see if people still loved me,” she told HuffPost of her comics last year. “I didn’t do it on purpose ― to shock ― but it was shocking to people. I did it because I needed the ultimate approval.”

Today the significance of Kominsky-Crumb’s oeuvre — not only to emerging comics artists but also to writers and comedians well outside the comics industry — cannot be overstated. “Before her era, I’m not sure there was a comics landscape for women,” comic artist Leela Korman said.

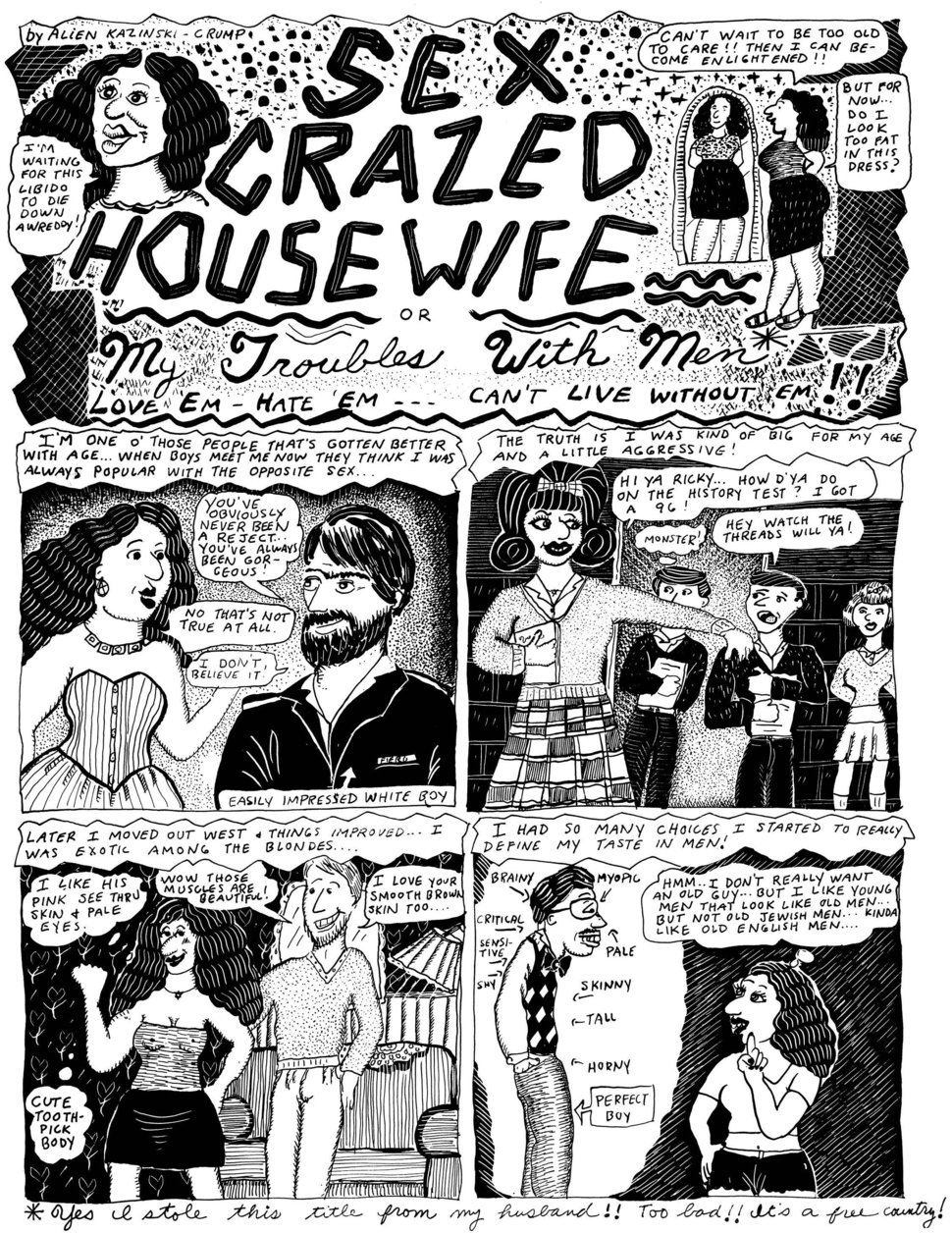

Before there were female comic pioneers to emulate, Kominsky-Crumb’s work invoked, as artist Vanessa Davis put it, a “freewheeling human grotesquerie,” an unfiltered look into a woman’s bedroom, body and innermost psyche as immediate and satisfying as an IV drip. Flipping off traditional (male) notions of artistic virtuosity with one hand and feminist prerequisites of respectability politics with the other, she singlehandedly set a precedent for women who use their lives and trauma as raw material in their creative work — Phoebe Gloeckner, Sheila Heti, Michelle Tea, Alison Bechdel, Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Lena Dunham, Rachel Bloom.

Almost 50 years into her career, Kominsky-Crumb is an underground hero whose enduring influence isn’t quite so underground.

Kominsky-Crumb started making comics in the 1970s after graduating from the University of Arizona with a fine art degree. To her, comics ― which she makes using only pen, paper and a copying machine ― offered an immediacy and intimacy the art establishment at the time sorely lacked.

“[Comics] were completely irreverent, very personal, saying ‘fuck you’ to everybody,” she said in 2017. “And it was cheap ― meant to be read and thrown away ― the opposite of precious, fine art. I wanted to do stuff that people like me could buy really cheap, read on the toilet and throw away.”

So she moved to San Francisco, the hotbed of the underground comix scene, after college. There, a boundary-squashing space that flagrantly flouted the Comics Code Authority’s prohibitions on sex, drugs and violence in mainstream comic books bloomed. Though the underground goods were banned from comic stores because of their lewd subject matter and unorthodox style, they wended their way into the hands of fans via head shop vendors or street sellers ― sometimes for no money at all.

Kominsky-Crumb published her first comic in “Wimmen’s Comix,” an entirely women-made underground journal that offered a feminist retort to the overarching bad boy mentality of the countercultural moment ― a consequence of the comix world being predominately male. With sex as prized subject matter, there was, as Hot or Not: 20th-Century Male Artists author Jessica Campbell recalled, a “rich tradition of male cartoonists using their work as a platform to describe their ideal woman’s body.”

One such artist was Robert Crumb, known for his expressive draftsmanship and his unfiltered representations of sex, serving up everything from incest to sexual sadism in sharp-edged detail. Kominsky-Crumb met him shortly after she arrived in San Francisco; he was the most renowned comic on the underground scene. When she showed him her work, he was a fast fan; she recalled, “He laughed so hard, he fell to the ground.”

The two eventually fell in love and married in 1991. Crumb’s notoriety brought attention to Kominsky-Crumb’s talent, though his controversial persona alienated her from the most radical corners of the feminist comics club.

The two are the reigning king and queen of NSFW graphics. In terms of artistic style, both are bold, nasty and gloriously crass. But their perspectives and artistic styles differ dramatically.

Crumb captures the unbridled male id in an expressive language that doesn’t hide its chauvinist or disturbing undertones; his images of sturdily built women with overripe curves amplify the male gaze to cartoonish proportions. Kominsky-Crumb shows that women can be just as dirty, hilarious and depraved. Her drawings demonstrate the fluctuating and complex relationships women have with their own imperfect bodies. While he visualizes unspeakable fantasies, she brings readers face to face with reality.

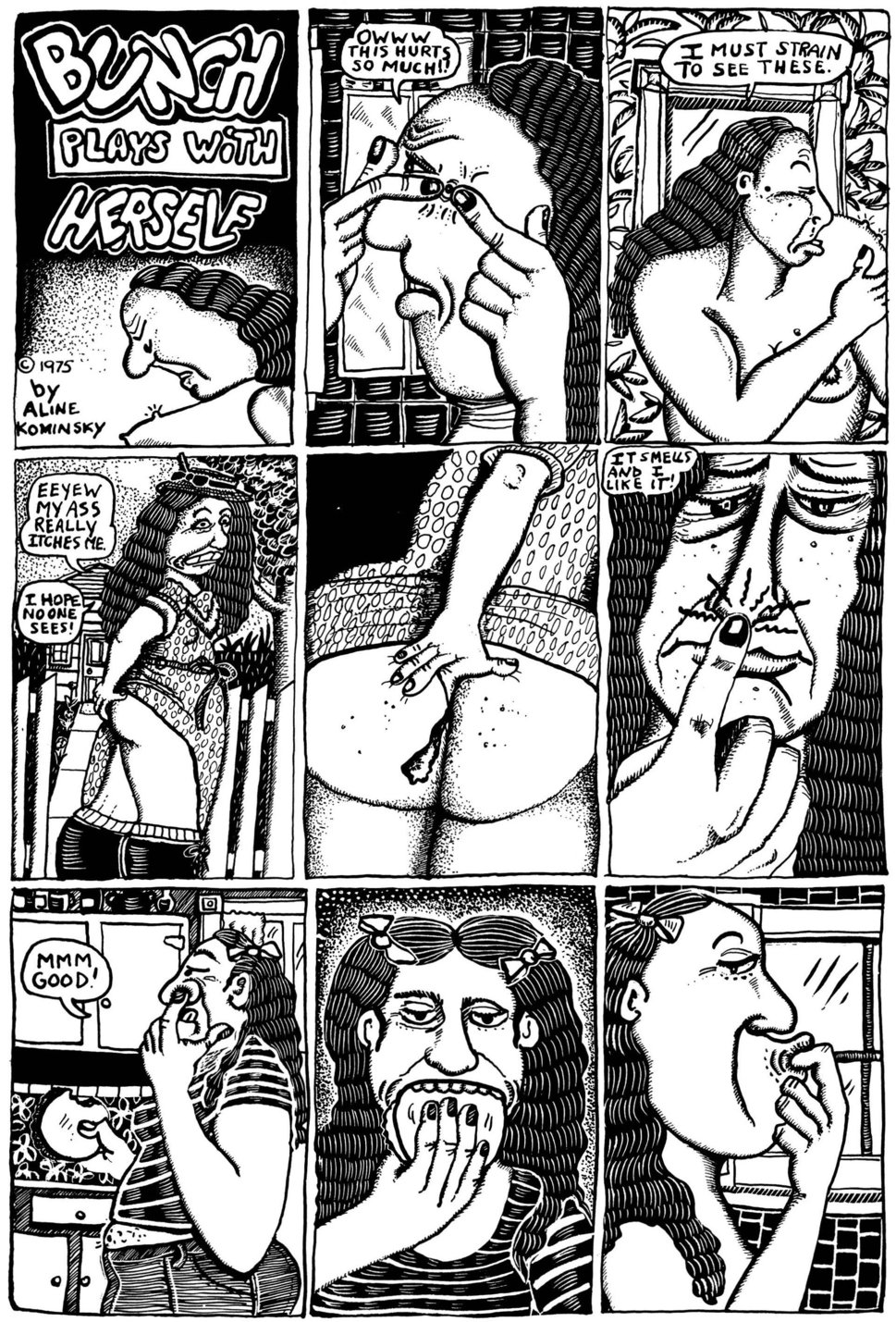

For example, in one of her early comics, 1975’s “Bunch Plays With Herself,” Kominsky-Crumb zooms in on her body as a site of grotesque fascination and infinite amusement. In the first panel, Bunch is topless and looking in a mirror, her body appearing burly and erratic. In the subsequent panels, it changes shape, depending on her posture and vantage point. Women who have spent too much time analyzing themselves naked are familiar with the anomaly.

The Bunch, constantly pointing our her various lumps, bumps and “big fat beef,” counters the slew of idealized, objectified female bodies with one that’s the site of hunger, lust and agency. She probes her itchy butt crack with her finger then brings it to her nose. “It smells and I like it!” she says, an outburst of black squiggly lines representing the odor. As far as Kominsky-Crumb’s work goes, this snippet is relatively tame. Flip the page and the reader is staring head-on at naked Bunch, reclining with her legs spread wide, using her fingers to play with the folds of her vagina.

“Ohhh ahhh ahhh be be be,” she moans.

Campbell describes Kominksy-Crumb’s work as having an “abject quality.” Her sloppy style meshes with her dirty subject matter to create a rat king of magnificently bad taste. In fact, after first encountering her work, Campbell said, she “misread it as being badly drawn.”

When you look at what has been considered canonical in the history of comics, it’s often very linked to the idea of the master draftsman, which is in turn linked to patriarchy.

Jessica Campbell, author, “Hot or Not: 20th-Century Male Artists”

“Now I see the rejection of virtuosity as its primary strength,” she continued. “When you look at what has been considered canonical in the history of comics, it’s often very linked to the idea of the master draftsman, which is in turn linked to patriarchy, but Aline refuses this system.”

As Campbell put it, in “opting out of the hierarchy of the virtuoso,” Kominsky-Crumb privileges voice and originality over tradition and perfection. There’s no hint of imitation, pretense or self-censorship.

“It feels like she’s talking straight to me,” cartoonist Carol Tyler said.

A woman representing her own sexuality with such unabashed chutzpah would be noteworthy in 2018. But Kominsky-Crumb presented viewers with the cross-hatched folds of her labia, liquid oozing out from between them, in 1975. It was this bad girl streak that ultimately separated her from her stringent feminist contemporaries. “Sex was too much fun. I didn’t want to give it up,” she told HuffPost. “I was very conscious of the entire feminist movement, but I realized there was an extreme part of it I couldn’t relate to.”

In ’76, she broke away from the Wimmen’s Comix Collective to begin another all-female anthology, “Twisted Sisters,” alongside comic artist Diane Noomin. “Working together was easy and fun,” Noomin wrote in an email to HuffPost. “The deal was we each traded pseudofeminist support for complete control of our own work.”

In the 1980s, Kominsky-Crumb became the editor of “Weirdo,” a respected alt comics anthology, solidifying her influence in the comic sphere. Alongside their individual work, she and Crumb collaborated on “Dirty Laundry,” a comic about their relationship, which later featured work from their daughter, Sophie Crumb, a gifted cartoonist herself. They even worked together on strips for The New Yorker.

Eventually they relocated to southern France in 1991, fed up with the censorship they experienced in the American comics world.

Today comic artist Mary Fleener, the creator of “SlutBurger,” believes we’re living in the golden age of comics made by women. In large part, this groundswell of bold and challenging work from female creators stems from Kominsky-Crumb’s example.

The comic genre is often equated with the clean aesthetic and formulaic plots of superhero sagas, in which brawny dudes in capes rescue chicks with lithe and lifeless bodies as they remain, for the most part, silent and oh so grateful. The protagonists’ values ― of courage, duty and justice ― are most often as fixed and unwavering as their gelled curls.

Kominsky-Crumb’s appetite for maximalism and slop unites her aesthetic and thematic interests, offering a salty antidote to the repetitive tropes of Marvel and DC comics. In her flat-out defiance of superhero tradition, however, Kominsky-Crumb becomes a kind of horny, abject superhero herself. Instead of a cape and tights, she wears miniskirts, tube tops or nothing at all, her body a funhouse of hairs, bulges and bumps. Her superpowers include sticking her tongue out to greet an airborne spurt of ejaculate and talking to her daughter about sandwiches as she fantasizes about being spanked by a man screaming, “You will obey me brat!!”

Kominsky-Crumb is most compelling in these moments, when her brash confessions don’t fall under the category of “brave” or “feminist.” The more Bunch embraces her monstrous side, the more the reader embraces her own.

“An Aline comic isn’t a powderpuff act of navel gazing or a politically correct wish list of utopian fantasies,” Fleener said. “It’s a hard look in the mirror and a lesson in acceptance and learning to laugh at weirdness around you.”

[ad_2]

Source link