[ad_1]

A woman named O sits in the backseat of a car, her underwear stuck around her knees, her thighs and ass pressing against the leather seat. O’s face is flushed, and her gaze is askew, communicating some combination of alarm and arousal. You can almost hear her inhale and exhale, deeply yet with unease.

The image is the first of artist Natalie Frank’s newest series of pastel drawings, now on view at Half Gallery in New York City. They’re based on the notorious Story of O, a famously filthy erotic novella published in France in 1954 under the pseudonym Pauline Réage. Forty years later, French intellect Dominique Aury revealed herself to be the writer. It was a jolt to the work’s many readers — including Albert Camus — who believed women were not capable of conjuring such wicked fantasies.

In the decades after its publication, O became wildly popular and wildly controversial. In the 1970s and 1980s, some anti-porn feminists railed against it, deeming its explicit content pornographic, dehumanizing and ultimately detrimental to women’s fight for equal rights. In a twist of fate, Frank’s visual interpretations of Aury’s literary smut faced similar allegations in 2018.

Frank’s show was originally slated to go on view at Sara Kay Gallery, owned by Kay, the founder of the nonprofit Professional Organization for Women in the Arts. But she withdrew her offer to exhibit Frank’s work a few months before the show was set to open, claiming the paintings might traumatize assault survivors, especially in the midst of the Me Too moment. “It was a difficult decision, but I had a very real concern that the content of Story of O could act as a trigger for victims of abuse and violence,” Kay told New York Magazine.

The fact that a midcareer feminist artist was censored amid the Me Too reckoning ― intended to heed the stories and experiences of women ― is an unfortunate reflection of the gendered power imbalance that has plagued creative cultures for centuries. Representations of female sexuality are among the most historically coveted and acclaimed artworks of all time, when they are generated by men. However, when female artists like Frank attempt to represent their embodied sexual psyches, they are rewarded with the very same lopsided treatment that penalized Aury and her erotic novella in the 1950s.

According to Frank, Aury’s text is a feminist triumph. In writing O, Frank believes, Aury posited in no uncertain terms that a woman’s most formidable erotic tool is her mind — a contentious idea indeed.

“I’ve always thought of O as a fairy tale for the modern feminist woman,” Frank said in an interview with HuffPost. “A woman who seeks to question identity and power structures while being upfront about sex and her own desires.”

Her interpretation echoes Aury, who described the book as “a fairy tale for another world.”

Frank is a feminist artist whose warped, figurative work invites viewers into the haunting spaces where desire, power and fantasy get tangled up and fleshed out. She first encountered The Story of O in a Texas bookstore when she was 15 years old. “I think it was the first erotic book I read that was written by a woman,” she recalled in an interview published in Half Gallery’s exhibition catalog. She has read the novella every year since.

For those unfamiliar with the story, here’s a rundown: A fashion photographer named O, passive and naive, is taken by her lover to a château in France, where she learns the rituals of sexual submission. Within the confines of the castle, O is pleasured, tortured and debased. She endures it all out of love for her paramour.

“I’m going to put a gag in your mouth, O, because I’d like to whip you till I draw blood. Do I have your permission?” Sir Stephen, one of O’s sexual masters, implores. “I’m yours,” she replies.

Over the course of the book, O is whipped, chained, branded and bruised; her anus is stretched and one of her labia pierced. She engages with men and women, as both sub and dom, eventually losing grip on herself within the rabbit hole of sexual inspection.

However, crucial to the plot of O is that all of its leading woman’s erotic endeavors are consensual. When O arrives at the mansion, she’s briefed on everything that goes on there and permitted to leave at any time. O becomes a sexual slave of her own volition; her torment is her choice. Aury believed O’s radical submission was anything but a sign of weakness.

“I think that submissiveness can [be] and is a formidable weapon, which women will use as long as it isn’t taken from them,” she told The New Yorker in 1994. “Is O used by René and Sir Stephen, or does she in fact use them, and … in some surreptitious way, isn’t she in charge of them? Doesn’t she bend them to her will?”

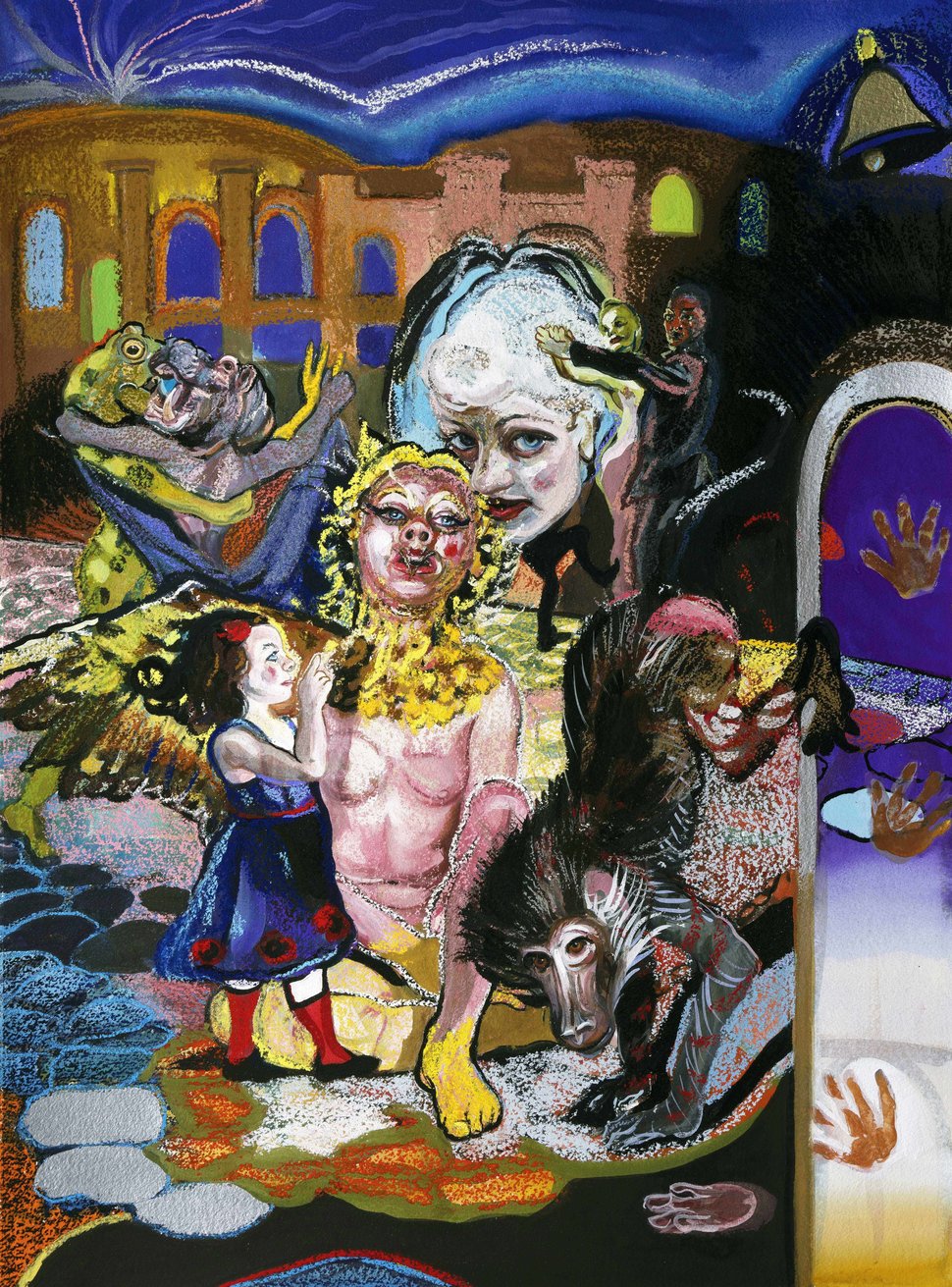

Frank’s disorienting pastels invite viewers into the NSFW manse, an acid-laced funhouse filled with dancing frogs, hippos, green-faced bogeymen and masked lovers. Yet the drawings linger more on O’s internal metamorphosis than her physical surroundings or configurations. With each passing image, O’s flesh seems to morph in chemical composition, heating up and then evanescing into a neon vapor. Frank homes in on O’s experience of pleasure, the way it contorts her body and explodes her sense of self.

Attraction and repulsion are opposite extremes whose ultimate proximity is a beloved artistic trope, but Frank’s specialty is juxtaposing humor and horror with deft agility. In one image, she conjures visceral freakiness simply by flipping an eyeball upside down. In another, she tempts the viewer to focus on O’s teeth-gritting grimace ― trapped between pleasure and pain ― as a prim grandmother in the back corner appears to be on fire.

The series’ grisly aesthetic eerily foreshadows the panic-stricken reaction it received from Kay. And, more generally speaking, the way women’s eroticism is cast as monstrous and deemed worthy of censorship. As curator Veronica Roberts, who worked with Frank in the past, asked New York Magazine, “Why is it that female desire is something which is so scary?”

For Frank, an outspoken critic of gendered discrimination and harassment in the art world, Kay’s decision to cancel her exhibition was “curious.” For the entirety of her career, Frank has depicted women’s experiences of pleasure and pain, often using source materials by underacknowledged female creators as inspiration.

In 2015 she visualized the Brothers Grimm’s 19th-century fairy tales ― far cries from the sanitized, whitewashed versions in Disney movies and childproofed bedtime stories. Centuries before Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm documented the stories, they were concocted and circulated orally by women “in the well or in the nursery or in the home,” as Frank told HuffPost in 2015.

Two years later, she exhibited a series of paintings of dominatrixes and ballerinas, both bodycentric professions intimately embroiled with the notions of fantasy and control.

It is curious — though not surprising — that Frank’s work was censored during a cultural moment that’s ostensibly about foregrounding women’s experiences of sexuality. Kay’s apprehension mirrors those vocalized by anti-porn feminists like Andrea Dworkin about the original O text. Over 40 years after she dubbed the book “a story of psychic cannibalism, demonic possession,” people are still resistant to the idea that a woman can pull graphic and perverse material from her own mind.

“Men have been making work out of their own desires for centuries. Women have desires too,” Frank told HuffPost. Art history is clogged with erotic depictions of passive, pretty women, each affirming the gendered power dynamics of the status quo. Often the conditions of the artworks’ creation are far more troubling than the final products, with artists from Pablo Picasso to Nobuyoshi Araki accused of mistreating the women who sat for them.

Just a couple of weeks ago, however, a Picasso painting of a nude pubescent girl sold for $115 million at Christie’s, and Araki’s work remains displayed in a sprawling retrospective on view at the Museum of Sex. A Chuck Close exhibition was postponed after allegations of sexual misconduct emerged against him, but his work remains prominently featured in solo exhibitions and permanent collections around the world. Profanity in art is still framed as more pernicious than misconduct in real life when a woman is responsible.

By and large, problematic artworks by morally objectionable male artists remain celebrated benchmarks of high culture. “We can’t not show artists because we don’t agree with them morally,” Tom Eccles, the executive director of the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College told The New York Times. “We’d have fairly bare walls.”

His statement embodies the frustrating fallacy female artists are forced to swallow. Museum walls would not be bare without the works of acclaimed yet destructive artists; they would perhaps finally have room for the countless female artists who have, for centuries, been forced to compete for a few spots on the margins — if their perspective was not blotted out completely.

This pattern persisted before the 19th century, when the Brothers Grimm were credited for fairy tales generated and exchanged long before they entered the fray. It continued when Aury was accused of dehumanizing women for weaponizing her erotic imagination. And it exists today, whenever artists like Frank are censored for depicting images of female sexuality sorely lacking from the canon.

[ad_2]

Source link