[ad_1]

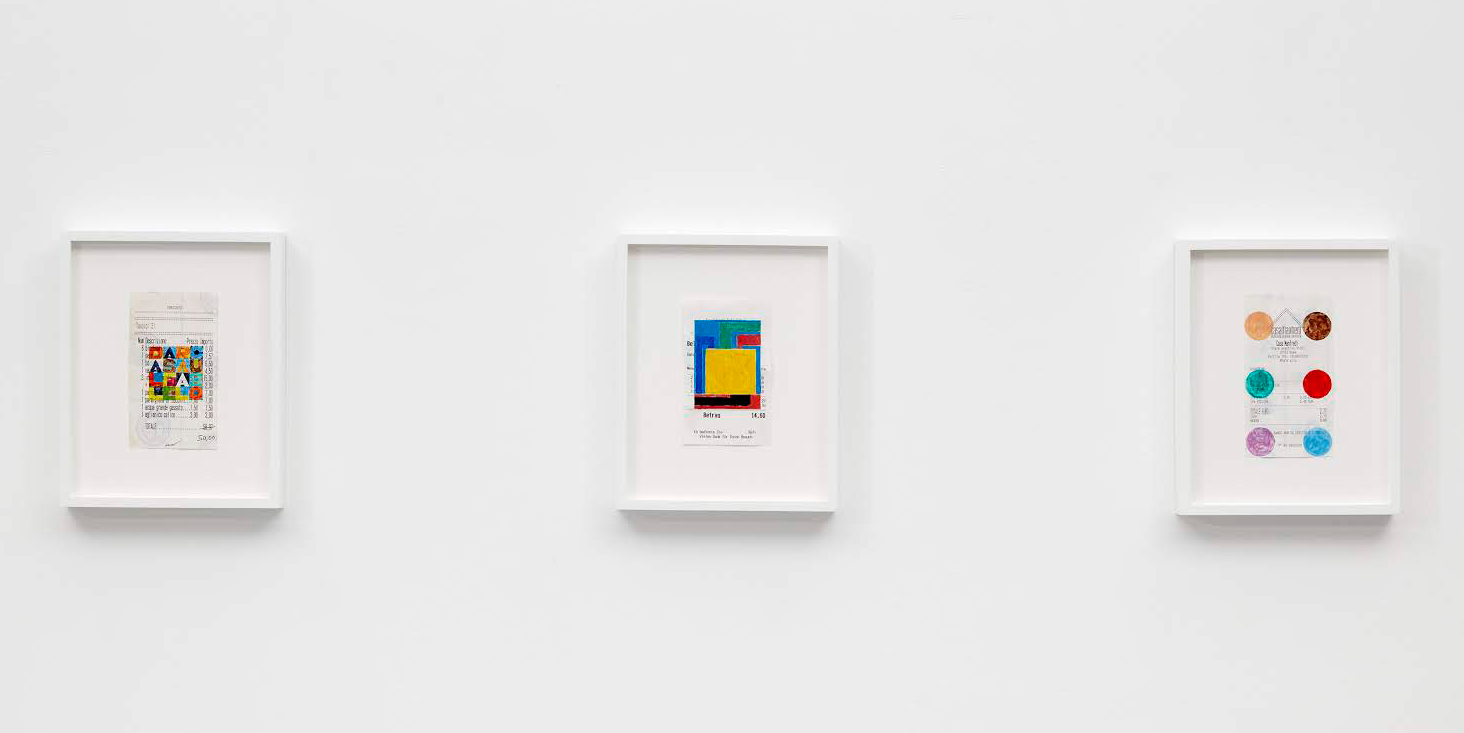

Jonathan Monk, “Restaurant Drawings,” Casey Kaplan, New York, 2019.

JASON WYCHE/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CASEY KAPLAN, NEW YORK

When Jonathan Monk goes out for dinner, he tends to eat freely—literally and figuratively—thanks to the very high likelihood that someone else will be footing the bill. But first he has work to do, after finding his way home—when he makes a drawing on his receipt, posts it to Instagram, and offers to sell the newly reconstituted readymade artwork for the price of the meal.

The figures aren’t so high, sometimes going as low as a couple dollars for a cup of coffee. But the true value is in a gesture that is self-sustaining and self-abnegating at once. “It was a nice idea that completed a circuit,” Monk said of a wry but also highly mindful project that he started three-and-a-half years ago during a stint living in Rome.

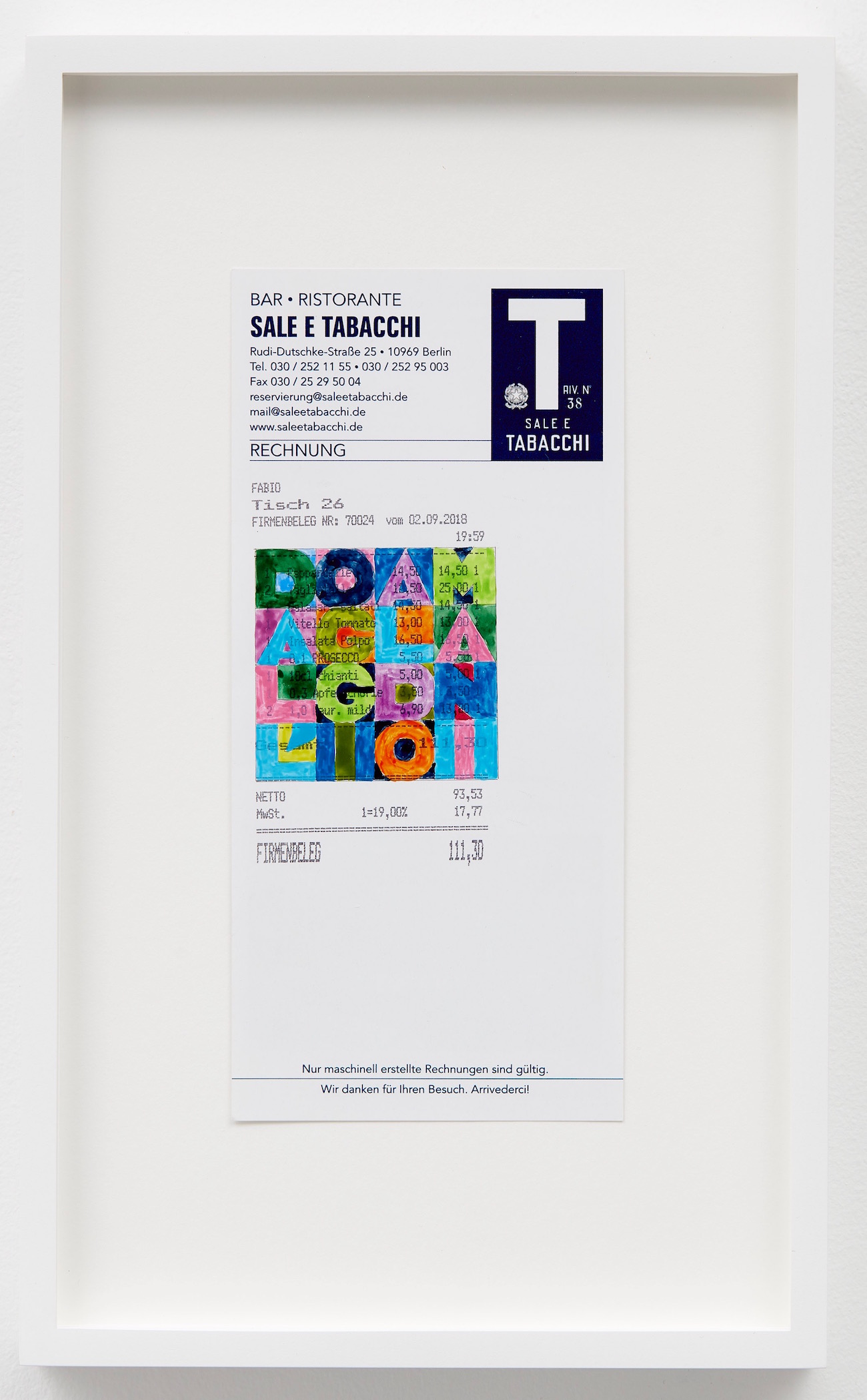

Jonathan Monk, Restaurant Drawing (L Weiner under the sun), 2018.

JASON WYCHE/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CASEY KAPLAN, NEW YORK

In Italy, receipts are often elaborate, with hand-scrawled notes and numbers that bear the mark of a server’s hand. “It’s not done on a computer—it’s a written receipt that the waiters add up and plonk on the table,” Monk said of the typical bill. As they piled up at home, the artist started to see them as a medium. “I didn’t have a studio then, and I wanted a project that would keep me busy and give me something to do.”

The circumstances of their sale connects to past works in Monk’s oeuvre, including a series of “Holiday Paintings” for which he reproduced on canvas advertisements for vacations listing locations and prices—and then sold the painting for the amount of the trip. He has also made work that includes instructions that it not to be sold for more than a certain figure. “The idea was that it couldn’t be resold for more, so it would essentially go down in value,” said Monk, who was born in Leicester, England, and is now based in Berlin. Then there were neon signs, such as one whose gaseous letters spell out the message “Do Not Pay More Than $60,000.” About works of that kind, the artist said, “That was more about the idea of negotiation. The collector could buy a $100,000 one for $40,000, if they were good at their job.”

The “Restaurant Drawings” are lower-hanging fruit, by design. The priciest one is no more than a few hundred dollars, with most much lower than that. “The idea was that I could draw on them and sell them for the price of dinner—essentially getting whoever it was to pay for me and my family to eat,” Monk said. “It wasn’t so problematic to go out. No one felt guilty, because someone else was paying. That was initially what was quite funny about the project.”

Enlisting Instagram to sell the “Restaurant Drawings”—which themselves are illustrations of other artworks by the likes of Sol LeWitt, Jasper Johns, Marcel Duchamp, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, On Kawara, and many more—proved essential to the project. “I’d never envisioned it as an exhibition because I thought it was one of the most perfect uses of Instagram I have ever seen,” said Casey Kaplan, the New York–based dealer who has worked with Monk since the 1990s—and who changed his mind to mount a playfully paradoxical exhibition that opens Friday and runs through July 27.

Jonathan Monk, Restaurant Drawing (AeB one day to the next), 2018.

JASON WYCHE/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND CASEY KAPLAN, NEW YORK

“Instagram has changed everyone’s attention span and the way we communicate with each other,” Kaplan continued. “The very nature of a family meal comes into question because of social media. How many times are you in a restaurant and you look over at a neighboring table and everybody is on their phone, not speaking to each other? For Jonathan to use Instagram as a utility and a currency—for Instagram and his followers to foot the bill for him to enjoy a meal with his family and friends—is brilliant.”

Monk said the show in the gallery—during which the drawings will be sold for the price of the meal on the receipt (none higher than €317—about $359) plus $150 for its white wood frame—closes a loop of a kind. “The whole Instagram thing breaking down the connection between the artist and the gallery was a starting point for the project, so the show in the gallery—Casey is very brave to do it. No one makes any money. We just break even, which is, in a way, quite good.”

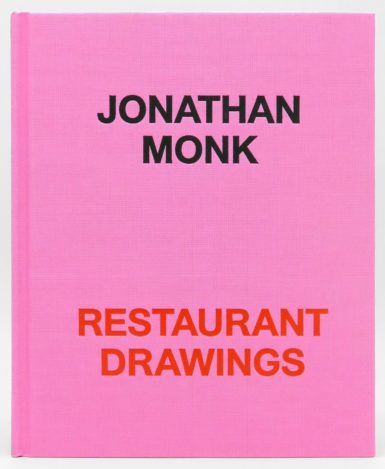

A publication by Karma, in an edition of 1,000.

COURTESY KARMA

Kaplan said the premise is part of the point of the show—especially after Art Basel, where artworks move for monumental prices in a fair setting that can be exhausting. “After Basel there’s a release, and it seems like an appropriate time to do something that is not about pre-selling and market strategies,” Kaplan said. “It’s just a celebration of the project and trying to be as inclusive as possible. The methodology of having a gallery space, with its vast expenses, and an opportunity for people to be able to come in and buy an artwork for €40 plus frame was really attractive.”

The show is also the result of thinking about the impending 25th anniversary of the gallery, which was founded in 1995. “It’s made me think about how far he and I have come together and how much the art world has changed, especially in terms of systems of value,” Kaplan said. “Jonathan was questioning value back in the ’90s, when it was incredibly difficult to sell work.”

Monk said the simplicity of the gesture of the “Restaurant Drawings”—which have been memorialized in a new 552-page book published by Karma, with a signing party at the Karma bookstore in the East Village scheduled for Saturday night—can be deceiving. “The drawing is quite easy, but then following up… Tax and accounts and invoices—they’ll probably become the reason I stop doing them. It’s the same amount of paperwork required for €20,000 as for €2.”

So the receipts for the receipts have become a problem? “In a way,” Monk said, with a laugh.

[ad_2]

Source link