[ad_1]

Four years ago, budding documentarian Liza Mandelup set out to explore the sway that social media holds on Generation Z. She stumbled into the world of live broadcasting, a deceptively complex ecosystem in which teenagers become famous among other teenagers by streaming earnest monologues on YouNow and by curating charming photos on Instagram.

The lucky ones might build a following, land a manager and fraternize with fans across the country, getting a taste of fame that was once reserved for rock stars and matinee idols. Meanwhile, loyal viewers watching at home experience a connection their social lives might otherwise lack.

But if live broadcasting is a young person’s game, every teen has to age out eventually. What happens when their glory comes crashing to a halt?

Mandelup’s work resulted in the revealing, empathetic documentary “Jawline,” which won a jury prize at the Sundance Film Festival in January. By profiling the highs and lows of social media stars, managers and admirers, the film pulls back the curtain on adolescence in the digital age without wagging its finger about “kids these days.”

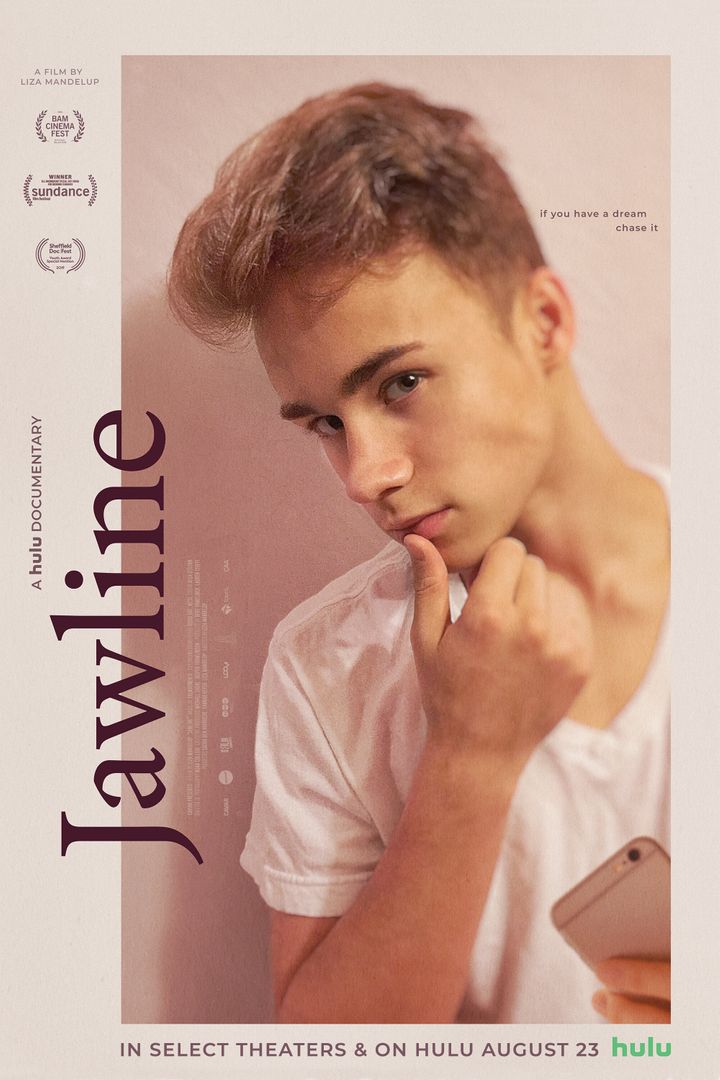

HuffPost is premiering the trailer ahead of the movie’s launch on Hulu and in select theaters on Aug. 23. We also posed a few questions to Mandelup via email about the process of making “Jawline.” Read them below our exclusive debut of the film’s poster.

What was your entry point into the world of social media influencers?

I started thinking about what it’s like to be a teenager today, navigating all the complexities of coming into yourself while also being bombarded by technology and especially social media. I started researching things that felt unique to this era of growing up and I found the world of “meet and greets,” which you see in the film. I’ve come up making films for various digital platforms, so I personally have had a lot of engagement with online worlds, but nothing like the world that you see in “Jawline.”

For the most part, you avoid explicitly charting the history of digital celebrities, which the average documentarian would be tempted to include. You also don’t pepper the film with academics weighing in on the phenomenon. Why was it important to make “Jawline” more character-driven?

The idea for the film was about exploring emotions. What’s it like to feel a connection to someone through a screen and how does that play out in real life? I was really interested in what it’s like to feel like you’re in love but know it only exists through this interaction on an app. What’s the moment like when, for the first time, you meet that person in real life? I wanted to tell a story in that space. This is how my process is; I always start with a feeling and a world and then I write the story within that. I was never interested in the dry facts and statistics. I always wanted to go back to how the teenagers were dealing with things on an emotional level. How are they getting by in this technology-filled landscape?

Your subjects are largely naive teenagers questing for fame while still trying to develop personal identities. Broadly speaking, how would you characterize their willingness to invite you into their lives?

I felt confident I would connect with teenagers because I remember being a teenager myself and wishing someone cared enough to ask me how I was doing. I understood that the teenage years are a time of loneliness and yearning to be heard by someone ― and now more than ever, this feels true. I felt like if I was someone who wasn’t too far off from their age, and who really cared, I would be accepted ― and I was. The world of live broadcasting is a world of teenagers looking to escape some element of their real life, so they’re looking for support and community. Our small film crew was able to fold into that. We were an adult voice of support and acceptance.

The central figure in the film is Austyn Tester, a 16-year-old who could be described as a motivational live-streamer. Given how camera-ready Austyn is, did you notice a difference in the way he behaved when he was being filmed as opposed to when he wasn’t?

I really never saw a difference, because Austyn is just who he is all the time. That’s part of his charm and what made me want to film with him in the first place. Sometimes we would stop rolling because we’d been filming all day and ran out of energy or card space, and he would still be going and doing things that could have slotted right into the film. I felt there’s a laissez-faire attitude about having yourself documented that comes with being a live-streamer that worked in our advantage. He was so used to filming everything he did that it didn’t sound crazy when we wanted to do that in our own way.

Through Michael Weist ― a wealthy, 19-year-old social media talent agent who sort of resembles a Hollywood suit ― we get a peek at some of the cutthroat economics behind the business. He’s often seen arguing with his clients and bragging about his expensive luxuries. How easy is it for teens to get taken advantage of by managers?

There definitely were a lot of managers that were chasing the “social media gold rush” that you see in the film. They saw an opportunity to succeed at something in a space that wasn’t dominated by a select few yet. Combine that with kids like Austyn who are young, inexperienced in business and don’t have a legal team or parents who know this world either, and that kid can get into a bad situation. Like signing a bad contract and going on tour with a bad manager who doesn’t have their best interest at heart.

I think Michael’s appeal to many of these kids is that he’s their age and of their generation. He acts as a perfect middleman between other industry people and the kids he’s managing. He can talk to the adult world, but he lives with and hangs out with all his clients. Michael is extremely transparent about the fact that he’s here to make money, and I like this about him.

What conclusions did you draw from this experience about the ways young people communicate today? Do you feel particularly troubled or encouraged by anything you encountered?

I think one of the reasons I was drawn to make this film and work on it for so long (four years) is because I couldn’t quite find one all-encompassing conclusion. So I kept looking and working through it. Why are all these kids here? What has made them so devoted to this live-broadcasting world? Is this good for this generation or bad? I kept asking myself these things. Online communities are incredible places for people to thrive and feel happiness and acceptance, and the live-broadcasting community is one of those places where people who have been rejected in other spaces have found a home.

At the same time, I think resorting to just an online community for happiness can create more loneliness. It’s a lot of time inside, alone in front of a computer or on your phone, not engaging with what’s in front of you. This is the complex nature of it. The more involved you become in your online self and the more you develop that persona, the more your real-life self can slip away. The more you find comfort in your life on the internet, the less interested you are in working through real-world issues.

A developing mind having to sort through who you are online and in real life can be very complicated. Coming of age is hard enough, and now it exists in the digital world and the tangible one.

Responses have been edited for style and clarity.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link