[ad_1]

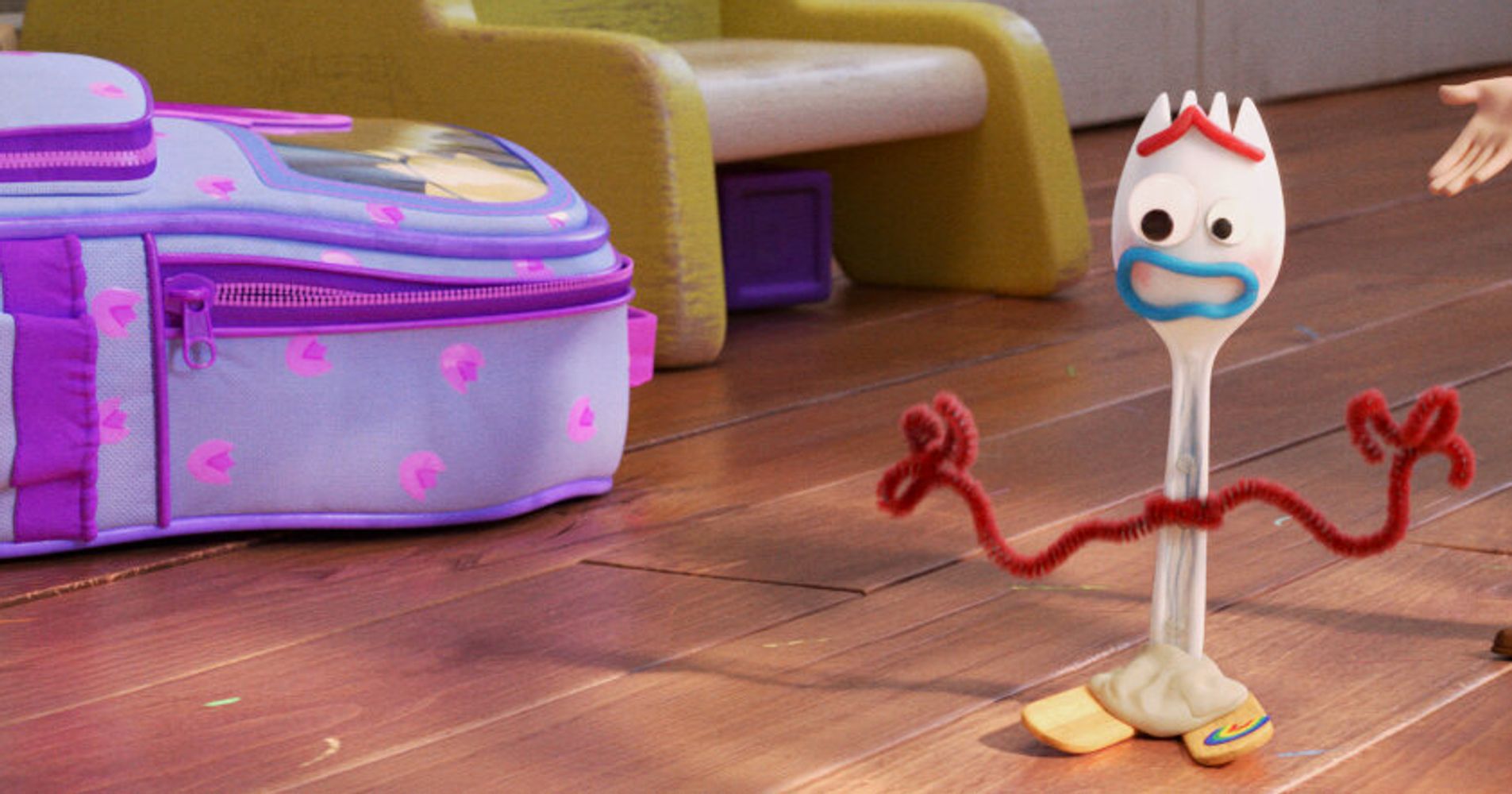

Each “Toy Story” movie introduces one key character who gives the franchise an excuse to keep going. In “Toy Story 2,” it was Jessie, the excitable cowgirl voiced by Joan Cusack. In “Toy Story 3,” it was Lotso, the ruthless bear played by Ned Beatty. And in “Toy Story 4,” which opened Friday, we get the Pixar series’ most complex addition yet: Forky, a spork with googly eyes, gangly pipe-cleaner arms and ice pop sticks for feet.

Portrayed by “Veep” and “Arrested Development” funnyman Tony Hale, Forky gains sentience at the exact moment when little Bonnie, who has inherited Woody (Tom Hanks), Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen) and the other toys, gives him a name. But Forky doesn’t consider himself a toy. “I’m meant for soup, salad, maybe chili and then the trash,” he proclaims after one of many suicide dives. It’s a profound existential quandary: Is his identity self-made, or is it dictated by others’ perceptions? Can it change over time? And how does it frame his mortality?

Throughout the film, Woody works to keep Forky from leaping into garbage cans, where he insists he belongs. They’re protecting Bonnie’s interests; she made him on her first day of kindergarten, and her happiness depends on Forky sticking around. What Forky doesn’t understand is how much some toys would give to be loved half as much as he is.

To find out more about how this self-destructive spork came to be, I talked to Hale, who said he treated Forky like a “small child” with a naive sense of the world.

At what point did you realize you were the breakout star of “Toy Story 4”?

Oh, I don’t know about that. I’m still trying to digest even being in it. It kind of comes in waves of realization that I’m actually a part of it. I think it was at the premiere a week ago that it really sealed the deal. I was like, “Oh, I didn’t make a mistake. Maybe I am supposed to be in this.”

Before taking the role, did you demonstrate what you thought Forky should sound like?

Yeah, when I went in, they had attached clips from “Arrested Development” and “Veep” to an animated Forky, so I knew they wanted him to have a neurotic energy, which is clearly, I guess, one of my fortes. So we kind of discussed that and then I played around with the voices. It felt very collaborative because they created a really warm environment where the actor is not separated from the writer and director. You’re in the same room, which is very different than typical voice-over in animation. I felt very much part of the process, and we played with ideas. After a day of playing around, we just seemed to kind of settle on a tone.

Tell me about that tone. It sounds like you’re softening or thinning your voice. Did it feel that way to you?

Maybe, yeah. I also think Forky is very much a small child. When my daughter was 4 or 5 years old, all she did was ask questions. That was it. It was one question after the next. Forky obviously has this incredible childlike wonder, so it was kind of getting to a higher pitch, but very childlike and gullible-sounding, very naive. For Forky, everything is new. He’s a completely blank slate, so when I was handed pages in the script, I had no idea what was going on. I just kind of played into this young child with a little bit of sass. Everything was so strange in the universe. He just has no clue — not to mention, yes, the “Toy Story” universe, but the universe in general. He was not even supposed to be alive, so it just felt like he was always in a state of “what the heck is going on?”

Did anything about the design of Forky change during the process?

I seem to remember there might have been a different sticker on his foot, and his eyes might have been placed a little differently, which makes me think about another thing that makes me laugh about Forky. Not only does he have no control as to what’s happening — he has no control over his body. His eyes are googly eyes, so they go all different kinds of directions. He has no flexibility in his body. He barely can walk. His arms have too much flexibility; they’re just all over the map. As a whole, he’s just floating around, completely clueless about what’s going on.

In the recording booth, did you find yourself doing something similar with your arms or your body movements?

That’s a good question because, coming from mainly doing comic acting on-camera, you get very used to your physicality. You get very used to using your eyebrows to punch a joke, or you get used to your eyes. And knowing that you just have the microphone to communicate the energy of Forky, I would do as much physicality in front of the microphone as I would if I was on camera. So as a way to channel that energy into the performance, my hands were all over the place, my body was all over the place. If anything, it was really tough to stay in front of the microphone to capture it. I was probably too crazy.

Was the “trash” motif as prominent from the beginning?

I remember saying “trash” a lot when it started. I think he always had this goal of just getting back to the trash. I will say, initially I just saw it as funny and silly that he was made from the trash and that was his home and it was squishy and fun. It wasn’t until months later when I came back to record that I really began to see — and maybe it’s because more pages of the script kept coming in — the depth of, not that Pixar is doing a message-driven piece, but the message that was organically coming out of the story with Forky, that he was made for more purpose and value than just the trash.

How did you conceptualize his dilemma? It’s universal in that everyone struggles to form their own identity, and often our identities are projected onto us by others and by the world at large. Forky already comes with a crisis: Is he a fork or a spoon? Now he has a second one: Is he a spork or a toy?

Yeah. I think it was more of him not knowing any better. He didn’t know anything other than trash. That was his only route, which made me think of anybody in this world who might have only seen themselves one way or have only been told they’re that way, and that there isn’t any other direction for them to take or a different way to think about themselves. Forky had his own awakening. And he obviously wasn’t pained about it — it’s all he ever knew: “This is the direction I’m made for.” And then he has this beautiful discovery of, “Wait a second. I’m made for a lot more than that.” It’s really beautiful how they constructed it.

If you had to estimate, how many times do you think you said the word “trash”?

Yeah, lots. I probably said the word “trash” as many times as Woody said, “Come on, guys.” I think Tom Hanks said that over the years he has said, “Come on, guys” so many different ways, and I can’t even imagine what Tim Allen’s version of that is for Buzz Lightyear. Forky’s version of that was definitely “trash.”

Right, because you have these little, manic soliloquies where you’re just saying “trash” over and over and over. Did you change the pace and energy of those from take to take?

If I’m honest, in my insecure brain, they didn’t sound very different. I was like, “Am I giving them something different?” As an actor, you really want to match whatever vision or plan they have for this character, so you keep putting stuff out, hoping that something is clicking with them. I think I just rambled about different stuff. Obviously, they were pleased and stuff did click, but in the moment I’m like, “I hope they’re getting it.”

Was there an improv that didn’t make it into the film that you were particularly fond of?

I can’t remember specifically what it was, but I remember I was shooting “Veep” at the time. The environment that I’m in on “Veep” is obviously very different than the “Toy Story” environment. So I think there were a few ad-libs that were colored from the “Veep” universe that clearly didn’t make it into the “Toy Story” universe.

A bit more adult, in other words.

Yeah. Yeah. I was so used to that atmosphere, and it probably bled into my recordings. They were like, “Yeah, we can’t use that.”

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link