[ad_1]

In the wildly popular Netflix show “You,” former “Gossip Girl” star Penn Badgley plays Joe, a handsome-yet-unassuming bookstore clerk who, when he’s not caring for the ancient novels in his shop’s basement, is obsessively stalking his girlfriend. Her name is Beck, and in an effort to secure her affections, he resorts to manipulating and eventually murdering several people she knows and loves.

Earlier this month, Badgley ― aka everyone’s TV crush circa 2007-2012 ― responded to the hordes of online fans who admitted to finding his “You” character attractive, to actively rooting for Joe in spite of his blatantly violent and controlling tendencies.

“Penn Badgley is breaking my heart once again as Joe,” one Twitter user wrote. “What is it about him?”

“A: He is a murderer,” Badgley matter-of-factly replied.

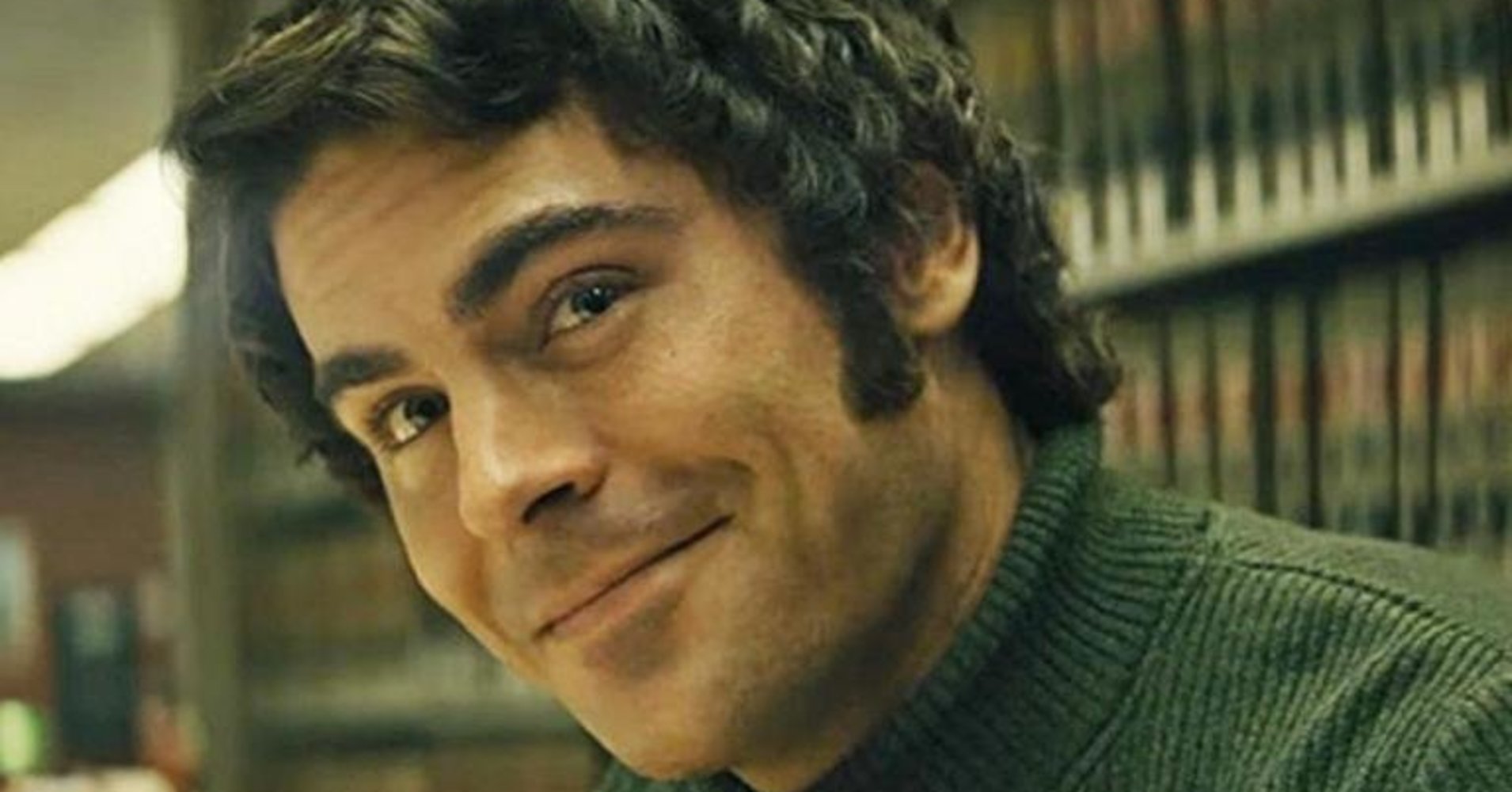

In the yet-to-be-released movie “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile,” another former all-American heartthrob ― Zac Efron ― plays another murderer with a complicated female following: Ted Bundy. In the film’s trailer, Efron-as-serial-killer grins, winks and charms to the tempo of a catchy rock tune. If you didn’t know better, you’d think you were watching a preview for a fun and fast caper about a relatively harmless criminal in the style of “Catch Me If You Can,” rather than a biopic about a monster.

The teaser, which dropped in late January, left a bad taste in the mouths of some people online, who blasted it for romanticizing a misogynistic rapist and necrophile who confessed to killing about 30 people in the 1970s ― and yes, was also attractive. The trailer plays up this quality ― perhaps, as others have pointed out, to make a point: The common narrative around Bundy is that he was able to get away with his unimaginably cruel acts for so long because he was exceedingly charming, clever and disarmingly handsome.

The common narrative, however, is wrong.

In many ways, true crime culture’s ongoing fascination with evil men like Bundy and the problematic reception of Joe on “You” seem to go hand in hand. We’ve been fed a line that serial killers are fascinating, evil geniuses whose misdeeds warrant a near-obsessive degree of analysis. And so documentarians and filmmakers and showrunners eagerly dive into the minds of these predators ― most of whom are white ― hoping to shed light on the inner demons that make our sociopaths tick.

But often, the mystery is less deep. Onscreen and off, whiteness is a shield that protects typical, everyday men from scrutiny. Being white is often associated with attractiveness, and attractiveness is often associated with decency, and together these associations help to provide cover. Neither Ted Bundy nor Joe needed to be exceptional criminals or atypically conniving people ― or even inordinately attractive men ― to get away with the horrors they enacted.

As Badgley, whose character on “Gossip Girl” turned out to be yet another man prone to stalking the people he hoped to control, put it: “Would anyone else be considered unassuming on the side of the street standing there too long? It’s pretty evident that no one but a young, handsome white man could do that.”

Refinery29 writer Ashley Alese Edwards recently declared as much. “The Ted Bundy of America’s consciousness is a myth,” she wrote. “Bundy was not special, he was not smarter than the average person; he did not have a personality so alluring that his female victims could not help but simply go off with him. … What Bundy did have was the power of being a white man in a society that reveres them.”

Would anyone else be considered unassuming on the side of the street standing there too long? It’s pretty evident that no one but a young, handsome white man could do that.

Penn Badgley, speaking of his “You” character Joe

Contemporary shows like “You,” movies like “Extremely Wicked” and docuseries like Netflix’s “Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes” are intended to illuminate the truths so many true-crime and serial killer-centric programs before them failed to do. They are ostensibly about broken systems that privilege some over others ― the intangible things that help murderers to get away with what they get away with. But no matter how hard they try, these projects inevitably fall into the precarious trap of perpetuating narratives about “fascinating” serial killers even as they attempt to dismantle them.

Instead, they rehash a story that’s been told several times before, they flatten some narratives and inflate others, and most importantly, they leave the viewer more preoccupied with the murderous men than the victims. Even on “You,” the audience gets so wrapped up in Joe’s journey to “win” Beck at all costs, that we forget that Beck is, in fact, a victim. In the case of Bundy, it’s easy to forget that his victims had stories of their own, too, when each woman’s body is primarily used to reveal another facet of her killer’s biography.

The question really boils down to: What is the value in rehashing these stories if they’re going to be packaged in the same way?

Early reviews of “Extremely Wicked” suggest that, unlike its trailer, the film takes a more nuanced approach to Bundy and his murders; it’s told from the perspective of Bundy’s longtime girlfriend, Elizabeth Kloepfer. But even if the movie resists romanticizing Bundy’s deeds in favor of condemning them (according to my colleague Matthew Jacobs, who saw the film at Sundance, there are two shots of Efron’s sculpted butt that, among other things, complicate the film’s intentions), the very existence of yet another Ted Bundy movie is a kind of romanticization, one with unwieldy results.

The “Conversations With a Killer” docuseries, for example, has garnered far worse critiques: The show was described as “cruel” and boring” in a review on Jezebel by Stassa Edwards, who also argued that it preserved “the tired narrative of the smart, good-looking serial killer.” On Vulture, Matt Zoller Seitz criticizes the four-part docuseries for focusing on Bundy rather than exploring the lives of his victims. Somehow the point continues to evade storytellers: Beyond the killings, beyond the killers’ minds, are actual human beings.

It seems that for stories like these to truly elevate the discourse around serial killers, there must be some value beyond simply getting into the mind of the man who kills. “You,” for instance, has sparked vital discussions about internalized misogyny that amounts to distrust of victims and the kind of toxic masculinity that masquerades as the opposite, by placing us in the killer’s mind and revealing that it isn’t all that interesting ― just delusional. Joe’s inner monologue isn’t a register of brilliant criminal strategizing; rather, it’s an average man’s earnest stream of consciousness that’s littered with entitlement and dispensation at every turn.

“You” has its flaws, but it seems far more self-aware of its place in the conversation than past serial-killer lore and “Conversations With a Killer.” Rather than just lead us blindly down the killer’s path of destruction, it challenges us to interrogate why we’re following at all.

[ad_2]

Source link