[ad_1]

Mary Wings knew she desired women way before she knew the word lesbian. When she finally learned the term at 21 years old, her first thought was how funny it sounded. She couldn’t stop saying it over and over ― toying with it and its various rhymes, letting the sounds roll around in her mouth until they felt at home.

But once Wings truly understood that lesbians ― and even more crucially, lesbian communities ― existed, she knew she wanted in. “It was like being in a giant wind tunnel and I just went,” Wings, 69 and based in San Francisco, told HuffPost over the phone.

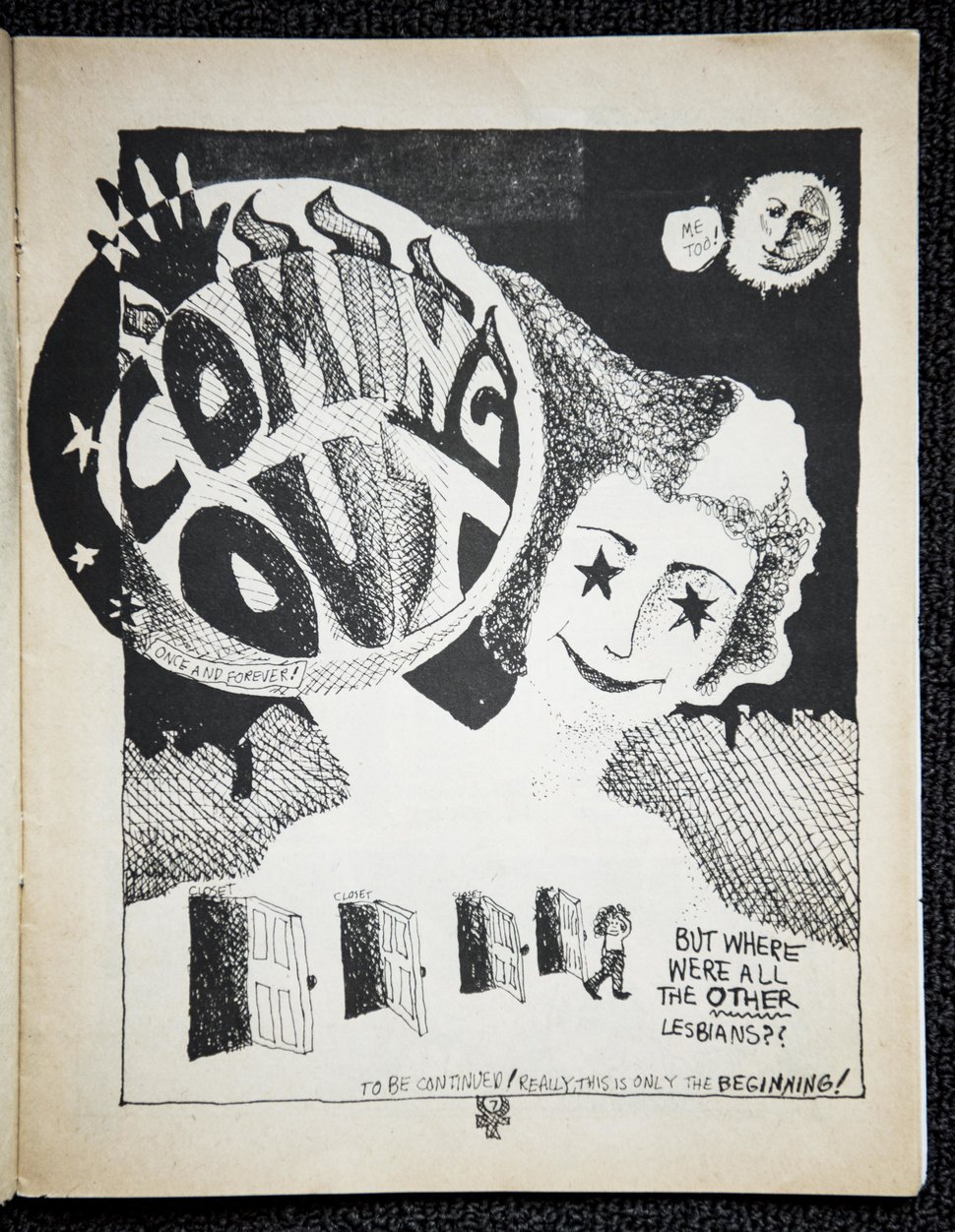

Wings created 1973′s “Come Out Comix,” what comic historian Justin Hall, the author of No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics, described to me as “the first, literary, queer comic book, created by and for queer people.”

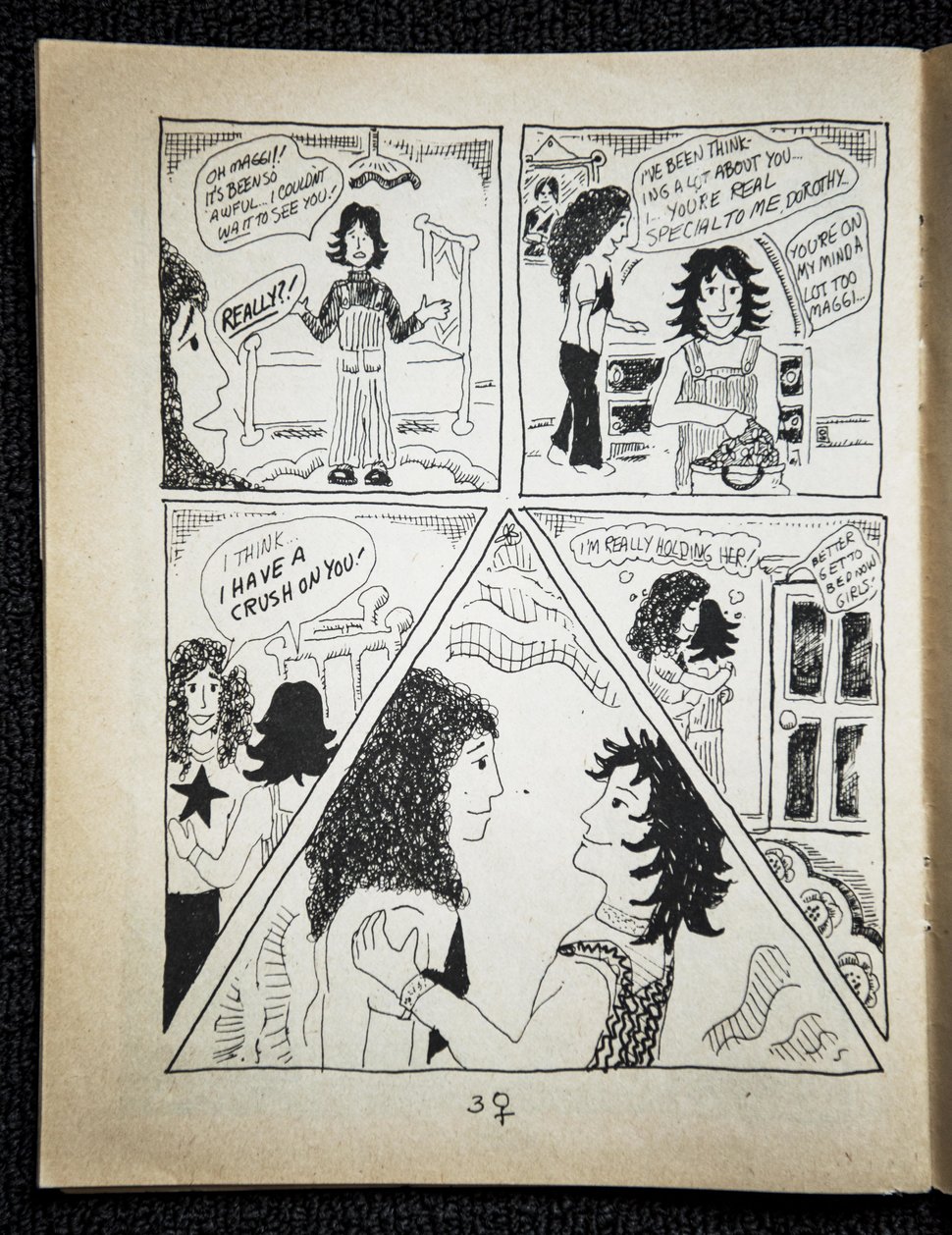

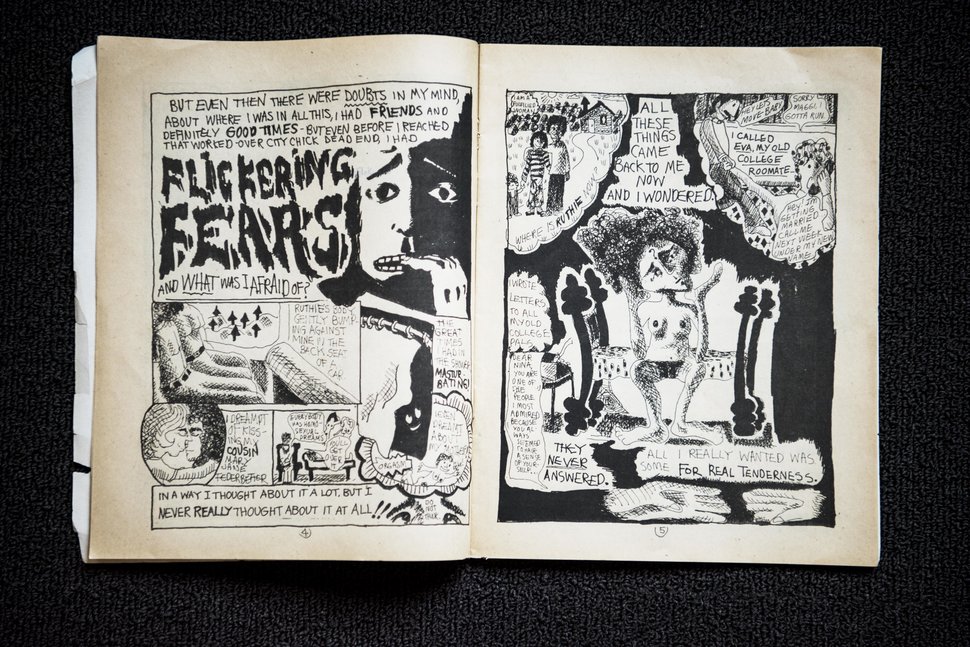

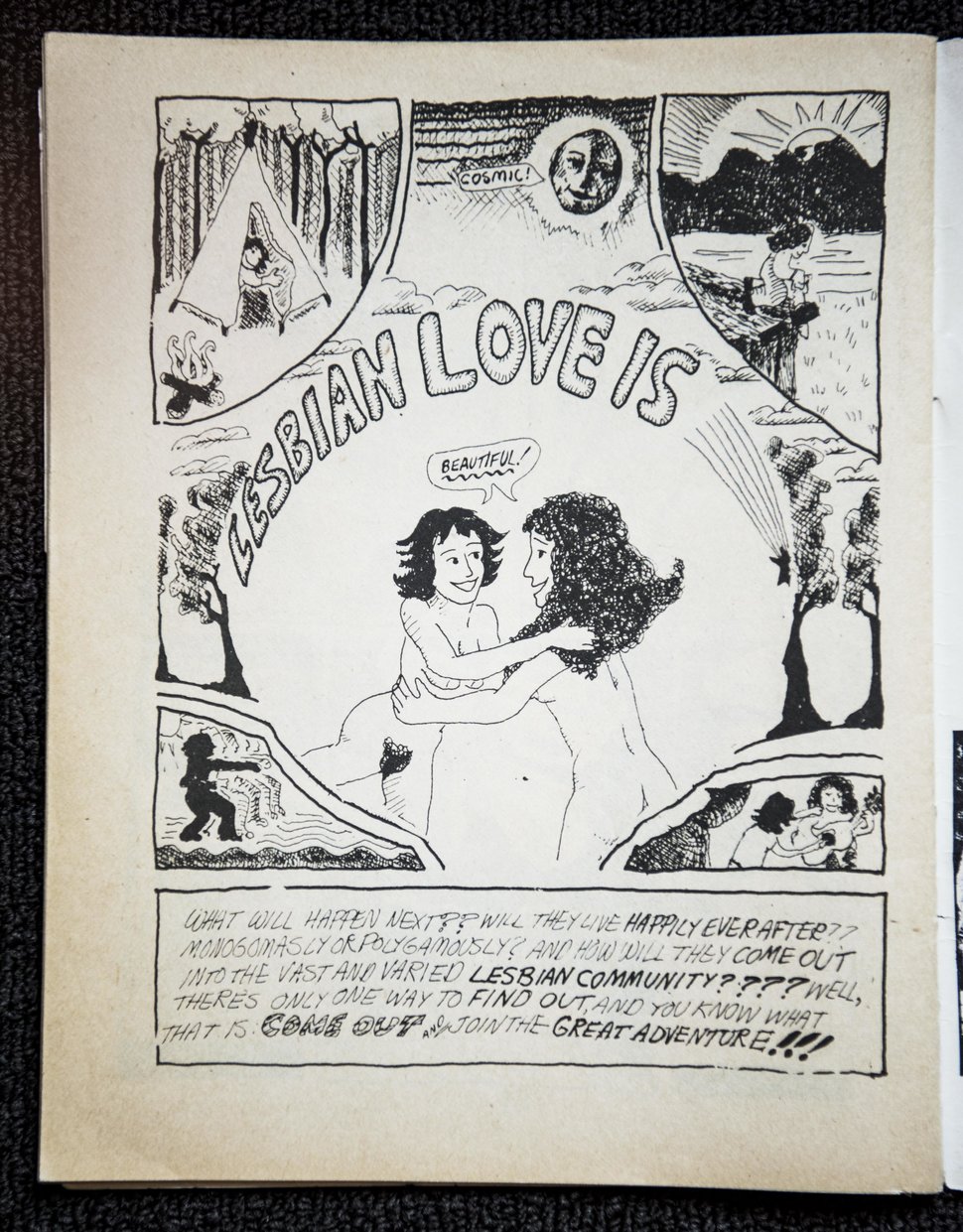

Aesthetically speaking, both Hall and Wings admit the book was ― and is ― on the raw side. The pamphlet tells, in rambling thought bubbles and crosshatch-heavy drawings, how Wings came out as gay, found a community and her first lesbian love. Yet its unapologetic bluntness and emotional generosity made the book an instant classic.

Shortly after it was published, the compact compendium could be found atop the toilet of just about every gay woman in San Francisco.

HuffPost

Some artists might squirm at the idea of having their work displayed on receptacles reserved for human excrement. But for underground comic artists, the image embodies the cheap-and-dirty glory of the medium, as comic legend Aline Kominsky-Crumb put it, “the opposite of precious, fine art.”

The underground comix movement in the U.S. sprung up in the 1960s in reaction to the Comics Code Authority, a self-policing effort formed in 1954 by the Comics Magazine Association of America to avoid government regulation of an increasingly controversial genre. The CCA placed draconian limitations on the comics sold in affiliated comic book stores, limiting the depiction of sexual innuendo, violence and profanity.

And so an underground comix movement bled from the industry’s profane underbelly into head shops and onto the streets, bringing with it tales oozing with sex, drugs and weird shit. Led by the likes of Robert Crumb (Kominsky-Crumb’s husband) and Trina Robbins, the movement eschewed censorship of all kinds and reframed the medium as a space to explore the most taboo of topics.

Yet, despite the freewheeling spirit of the underground comix, the loudest voices in the room were still often straight, white and male. The forbidden topics they explored usually involved unsavory male fantasies dripping with misogyny. Feminist and queer comics ― like Wings herself ― eventually clawed their way in. In the realm of comics, artists didn’t need much beyond will, pen and paper to do so.

“It’s not like making a movie where you need an enormous apparatus,” comic scholar Hillary Chute, the author of Why Comics?, told HuffPost. ”[Artists] were able to represent their realities while sitting in their apartments. There is a low bar to entry… you don’t need anybody else’s approval.”

Wings certainly didn’t.

“I just wanted to have an orgasm,” Wings candidly explained over the phone, a reference to her general mindset in the 1970s. “I had these boyfriends who were horrible. I thought, ‘I can do this myself in five minutes. What’s wrong with them?’”

Her frustration with men began at her Chicago home, where her father and brother treated her mother, who gave up on her dream of becoming an artist to raise a family, like a “waitress.” “I thought, I don’t want to spend my life dealing with this,” she said. “Heterosexuality looked like the patriarchy.”

When Wings was in her mid-20s, her mom was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She died 20 days later. “Her frustration was my great inheritance,” Wings said. “The minute she was out of the picture, I wanted to do all the things she didn’t do.”

HuffPost

And so she did. A yearning for the feminine freedom her mother never had inspired Wings to move west to San Francisco, where the queer, sexual revolution was in full swing. “We wanted to make a new world for women and for ourselves,” she said.

When she arrived in the Bay Area, Wings realized not only was she smack dab in the middle of a transformative moment in sexual politics and identity, but in comics as well.

One of the most groundbreaking comic books to emerge from this moment was “Wimmen’s Comix,” an all-women’s collection which debuted in 1972, exploring topics like menstruation and masturbation. The journal debuted the work of now iconic artists like Kominsky-Crumb and Diane Noomin.

Robbins, who compiled the collection, also submitted work that included a terse, three-page entry titled “Sandy Comes Out.” It chronicles Sandy Crumb’s experience coming out as a lesbian. (Sandy is Robert Crumb’s sister, and she provided input on Robbins’ narrative.)

“It was a good story, so I told it,” Robbins told HuffPost. “I never thought, when I was doing it, ‘Oh my gosh, this is the first comic about a lesbian.’”

But it was ― told in short, academic and to-the-point fashion. “Sandy, you must find a positive alternative to the dehumanizing nuclear family,” Sandy tells herself in the first panel. “Some way to smash phallic imperialism… Could it be that the only release from the yoke of macho oppression can be found in lesbianism?”

“Of course it is!” she concludes in panel two. Voila! Sandy came out.

When Wings saw the comic, she didn’t love it. She was floored by how cut and dry Robbins ― who was straight ― rendered Sandy’s coming-out process. Her decision to love women, it seemed to Wings, was depicted as a choice as capricious as “deciding to go brunette this week.”

As she wrote in an email to HuffPost, “I used to be Trina’s big enemy!”

To which Robbins responded, “I didn’t know she was mad at me!”

HuffPost

Not one to complain from the sidelines, Wings got to work. “I was just dying to respond [to Robbins],” she said. “I didn’t know what I was doing but I did it.”

At 23 years old, it took her just seven days to hammer out “Come Out Comix.” Instead of trying to articulate a universal coming-out experience, Wings honed in on the nitty-gritty details of her own sexual self-discovery.

“There was a lot of risk,” Wings recalled. She knew her youthful dreams of being a schoolteacher would be thwarted by publicly coming out. (In 1978, California proposed a law to prohibit openly gay and lesbian teachers from teaching in public schools. In the years leading up to the ballot measure ― which was defeated ― discrimination was rampant.)

“One of the right wing’s big beliefs was gays were proselytizing,” she said. “So I wanted to make sure I was proselytizing in the book.” To drive her point home, she drew Sappho ― the archaic Greek poet from the island of Lesbos ― dressed up as Uncle Sam and hollering “We want you!”

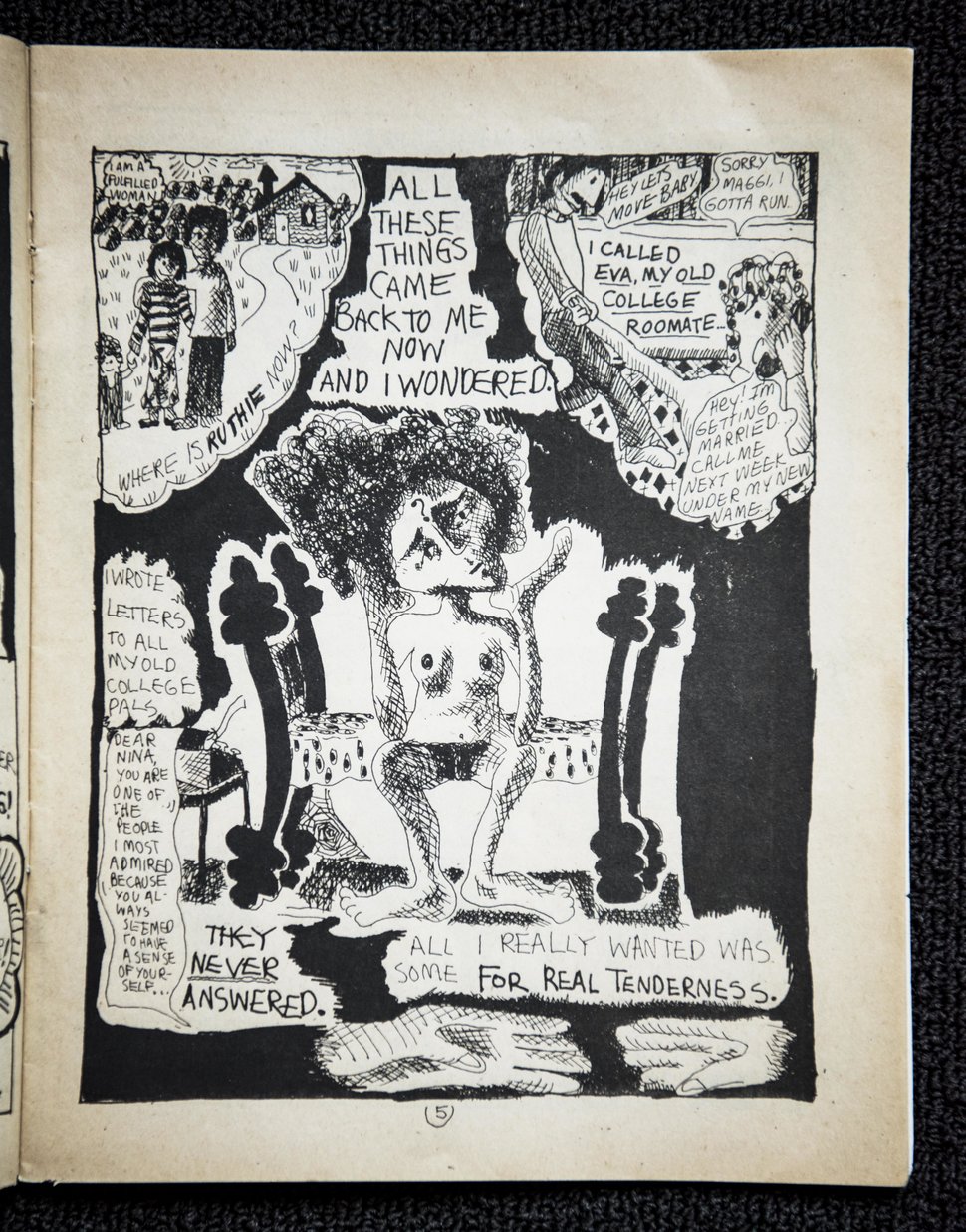

Wings’ comic includes intimate and sometimes humiliating thoughts that raced through her questioning mind at the time, like dreaming of kissing her female cousin. Eventually she comes to the overwhelming conclusion that “all I really wanted was some for real tenderness.”

The drawings are rough and rambling but demonstrate the frenetic pace of a mind in the process of an overpowering transition.

Notably, the comic doesn’t end with Wings’ realization that she’s gay. Readers follow her as she comes out to her girlfriends and attends her first lesbian gathering, a Halloween party where she dresses up as herself. Her tale includes the ways those within her social circle, most of whom were straight, responded.

“It seemed like everyone had a vested interest in keeping gay people in closets,” she writes after a frustrating experience with old friends. “Not just schools and parents and police.”

HuffPost

When Robbins finally saw Wings’ comic she thought it was “terrible.”

“She knows that, so it’s OK!” Robbins said. “But she was really, really terrible. She was a bad artist, but she’s so good now. That was like the stone age of comics, especially for women. Most of us had never done it before. People improve.”

For author Hall, one of the most compelling aspects of Wings’ comic is how it doesn’t just describe her coming out journey, it is the journey. “Coming out was fairly knew to her,” he said. “Creating the comic was part of her process and that comes through in the comic itself… I view it as the first lesbian comic book, but I would also say it’s the first queer comic book that was not erotic or derogatory.” (He cites Tom of Finland as the first queer, and very NSFW, comic artist.)

After Wings, the queer lady comics kept on coming. In 1976 Roberta Gregory released Dynamite Damsels, and, according to Hall, “hit the ground running with comics in a way that Mary wasn’t able to.” In 1975 Lee Marrs, who is bisexual, released The Further Fattening Adventures of Pudge, Girl Blimp, featuring the first openly bisexual character in comics. And in 1983 Alison Bechdel began publishing her queer comic strip Dykes To Watch Out For. In 2006, Bechdel’s autobiographical comic Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic made an unprecedented crossover to mainstream audiences, solidifying queer stories’ place in the comic canon.

“Fun Home was completely terrain-shifting for the comics world in general, not just for gay comics,” Chute said. “The fact that book was so acclaimed, on The New York Times’ bestseller list, and happened to be a memoir about a butch lesbian growing up in rural Pennsylvania with a suicidal father ― it showed that queer comics could be mainstream comics, and they were.”

HuffPost

Wings’ comic didn’t just alter the future of comics, it rerouted the course of her life. Two years after “Come Out Comix,” she started releasing “Dyke Shorts,” snappy comics centered around the experiences of queer women. She then pivoted to writing fiction and embarked upon the “Womansleuth Mysteries” series, starring lesbian detective Emma Victor.

“I didn’t mean to make a career out of making gay things, but considering how terrified I was to publish any of it in the first place, it turned out well,” she said.

As for Robbins ― her former comic adversary ― the two feminist pioneers eventually met in person and got along just fine. “We laughed and hugged,” Wings recalled, and any lingering animosity between them melted away. The two now often sit side by side at panels geared around pioneering women in comics.

Today, Wings is contemplating a return to comics to tackle another taboo she feels is underrepresented in the medium: aging.

“I have one part called ‘Things I Dropped Today,’” she joked. But the book will contain more serious elements too, criticizing medical facilities’ treatment of aging populations.

“I have to write the thing that hasn’t been written,” she said.

#TheFutureIsQueer is HuffPost’s monthlong celebration of queerness, not just as an identity but as action in the world. Find all of our Pride Month coverage here.

[ad_2]

Source link