[ad_1]

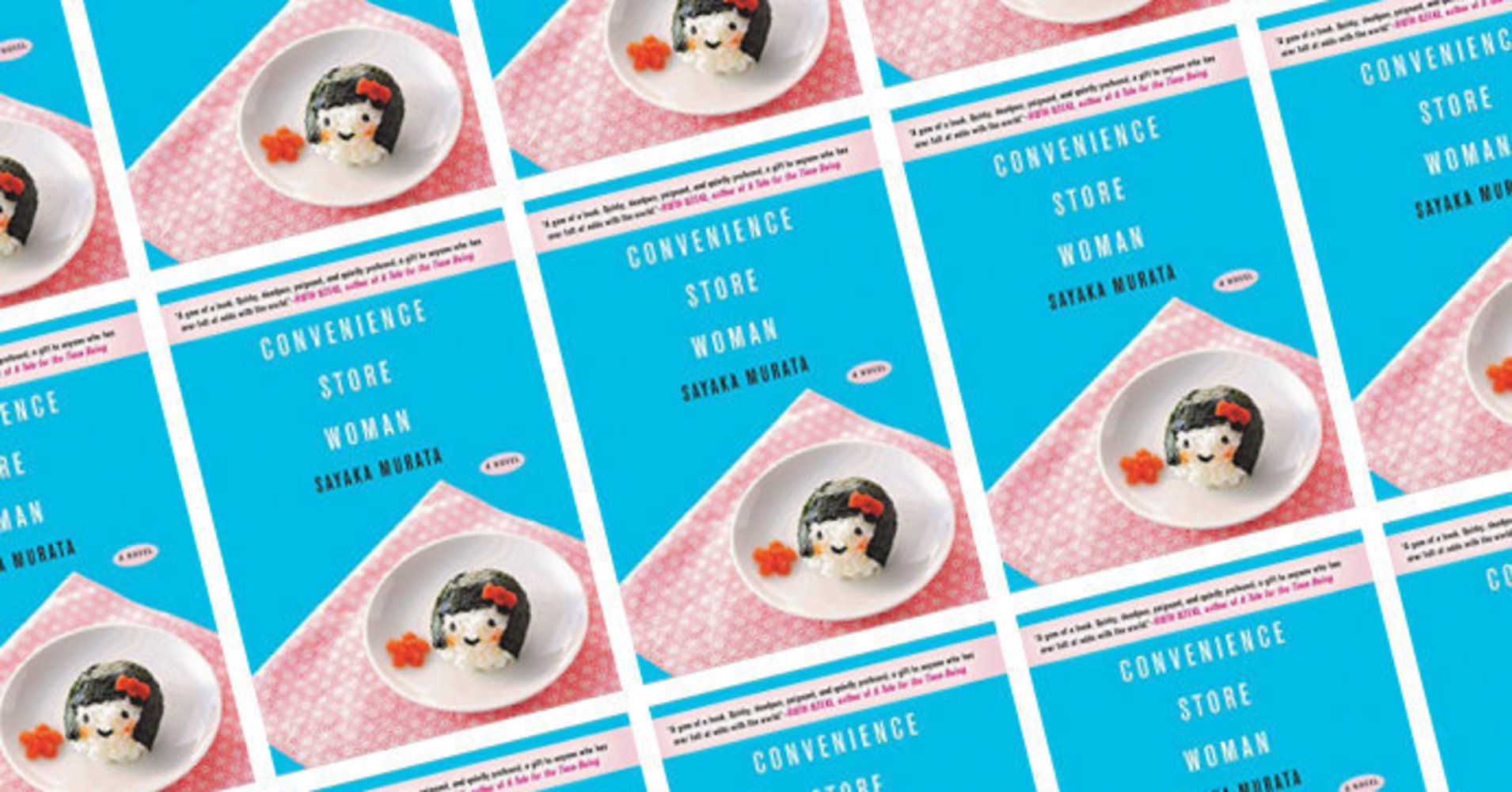

A perky face looks out from the pink-and-blue cover of the American translation of Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman, originally published in 2016 in Japan, where its publisher says it sold a stunning 660,000 copies.

The face is round, framed by a sleek seaweed bob, sitting on a small white plate. It’s smiling from the side of a rice ball, much like those sold to hungry businesspeople in the Japanese convenience store where the book’s narrator works. The little humanoid figure invites a smile in return, even as we hover over it, preparing to eat it. It’s conscious, but it’s also fodder, created to be consumed.

This tension animates Convenience Store Woman, a quiet novel about a 36-year-old woman, Keiko Furukura, who has been working at the same convenience store for 18 years. The work, often a last resort for people in between jobs or just starting their careers, has been her haven for half her life.

Keiko is a misfit of sorts, a woman uninterested in the societal structures ― love, marriage, childbearing, career ― that those around her have profoundly bought into. The novel, in a translation by Ginny Tapley Takemori that debuted in the U.S. on Tuesday with Grove Press, sets her on a collision course with the expectation that she’ll conform. As she tries to bargain for a way out, she encounters another convenience store worker, Shiraha, an outright misogynist who feels equally excluded from society. Eventually, she makes a wild proposition to him, in hopes that between their two outsider selves they can improve both of their lots.

In the ensuing fallout, Murata draws a poignant portrait of what happens when a woman’s oppression meets a man’s grievance ― and one of them has to give. Convenience Store Woman closely observes the inevitable failures of a society to embrace all within it, and the contrasting ways disenfranchised men and women manage to cope.

Since early childhood, Keiko has been aware that she is not like her family and acquaintances. She struggles to read social cues, and rarely understands others’ emotions. Once, in school, she picked up a shovel and bashed a boy over the head to break up a fight between two schoolmates. She was surprised when people responded with shock and admonishments instead of appreciation; after all, they had wanted the boys to stop fighting. “Why on earth were they so angry?” she thinks. “I just didn’t get it.”

As she got older, she lacked interest in career ambition, close friendships and romance. Her family sought out cures and cosseted her, hoping she’d grow into the same kind of person everyone else is. Instead, at 18, she gets a part-time job at a new convenience store in a business district, and discovers a tiny universe in which the rules of engagement are clear-cut and her value as part of the team is tangible.

She wears a uniform; she calls out canned lines, rehearsed daily before her shift; she stocks shelves, rings up purchases and keeps an eye on inventory and promotion. She never misses a shift.

I am one of those cogs, going round and round. I have become a functioning part of the world, rotating in the time of day called morning.

Sakura Murata, “Convenience Store Woman”

In the rest of the world, the range of alien human feeling is so vast it drowns her, but in the store, she has become an expert at understanding other people. “I automatically read the customer’s minutest movements and gaze, and my body acts reflexively in response,” she thinks, as she predicts from the motion of a shopper’s hand that he will pay electronically. She’s gathered that her co-workers seem pleased when she is upset by the same things as them, so she plays along with their workplace gripes. There are no shovel-to-the-head moments in this little realm, where she obeys all the laws.

“It is the start of another day, the time when the world wakes up and the cogs of society begin to move,” she thinks, early in the novel. “I am one of those cogs, going round and round. I have become a functioning part of the world, rotating in the time of day called morning.”

The words might sound grim, but Keiko is content. She likes fitting in, being useful.

Outside the convenience store, though, she remains a loose end. In her late 30s, she’s still single and hasn’t gotten into a career-track job. “While I was in my early twenties it wasn’t unusual,” she thinks. “But subsequently, everyone started hooking up with society, either through employment or marriage, and I was the only one who hadn’t done either.” Her sister has begun to overtly pressure her to find a relationship, and her friends and co-workers ask probing questions about why she’s still in a part-time job.

Soon a wrench is thrown into the cozy machinery of her convenience store refuge with the arrival of Shiraha. Like Keiko, he’s past the age when society would have expected him to settle into a career and family; instead, he’s single, working at a convenience store and, unlike Keiko, bitter about it. “We existed only in the service of the convenience store,” she thinks on his first day. “It appeared Shiraha had not yet come to terms with this.” He refuses to contribute. He uses his cellphone at work, to Keiko’s shock. (“I couldn’t understand why he’d violate such a simple directive.”) He complains about rehearsing the customer greetings. He’s late.

This noncompliance cannot stand, of course. It threatens the very existence of the store as she knows it. “A convenience store is a forcibly normalized environment,” she thinks after a clash with Shiraha. This world, she repeatedly notes, remains unchanged even as an endless cycle of employees and products pass through it ― a stasis that relies on every worker playing their part as written, with no deviations.

From the people down to the milk and eggs on the shelf, they’re all disposable commodities. This does not greatly bother Keiko; it’s capitalism distilled to its coldblooded essence. Every person and thing plays its part, and then is replaced, seamlessly.

What upsets her are the messier systems in which humans are expected to play a part and then be replaced. Pairing off and having children is the system by which society replaces itself ― but here, she is like Shiraha. She incorrigibly refuses to play her part and frustrates the smoothly functioning cogs around her.

For Shiraha, though, his single status and lack of career serve only to fuel his resentment and bigotry. Where Keiko is politely puzzled by love, Shiraha is enraged that beautiful young women don’t want to marry him. Where Keiko sequesters herself in a small, logical world where she can be useful, Shiraha flings himself in the face of society and demands the fruits of labor he doesn’t want to do.

He stalks a female customer, and regales Keiko with monologues that could have been drawn from incel message boards: “The youngest, prettiest girls in the village go to the strongest hunters. They leave strong genes, while the rest of us just have to console ourselves with what’s left.” Meanwhile, he dismisses potential love interests as “too flighty,” “too old” and “too domineering.” The hypocrisy does not seem to dawn on him.

I was beginning to lose track of what “society” actually was. I had a feeling it was all an illusion.

Sakura Murata, “Convenience Store Woman”

Unbothered by his vitriol, Keiko is able to handily dissect his arguments. When he complains that women will flock to him once he starts his hypothetical business, she points out, “Well then, wouldn’t the proper way be for you to do that first?” He has no reply. But when he complains that they live in a “dysfunctional society. And since it’s defective, I’m treated unfairly,” she finds herself agreeing. “I couldn’t even imagine what a perfectly functioning society would be like,” she thinks. “I was beginning to lose track of what ‘society’ actually was. I had a feeling it was all an illusion.”

Through the eyes of perceptive, dispassionate Keiko, the ways in which we’re all commodified and reduced to our functions become clear. What’s unclear is what other option we have. We all want to be individuals, and yet we also want to fit in somewhere. We all want to be seen for our own intangible humanity, and yet we see others for their utility. Even Keiko, who is bemused and irritated by the expectations placed on her by society at large, expects perfect order and compliance within her own miniature version of it.

If society is an illusion, it needs to be a collective illusion in order to sustain itself; as for perfectly functioning, each kind of society will function better for some than others. Were Shiraha to design his perfectly functioning society, for example, I expect women like myself would have some complaints. In their arrangement, meant to be mutually beneficial, Shiraha’s expectations eventually clash with Keiko’s and then take over. Even in a scheme dreamed up between the two outsiders, something has to give to create a sustainable system, and what must give are Keiko’s needs.

It seems all too fitting that Murata’s disaffected man, Shiraha, lashes out at a cold world with demands and reproach, while the female narrator quietly seeks out a space within that unwelcoming world where she can contribute. To anyone living in the world today, in Japan or the U.S., it should come as little surprise that the sharpest consequences for a man’s pain and a woman’s pain both fall, in the end, on women.

[ad_2]

Source link