[ad_1]

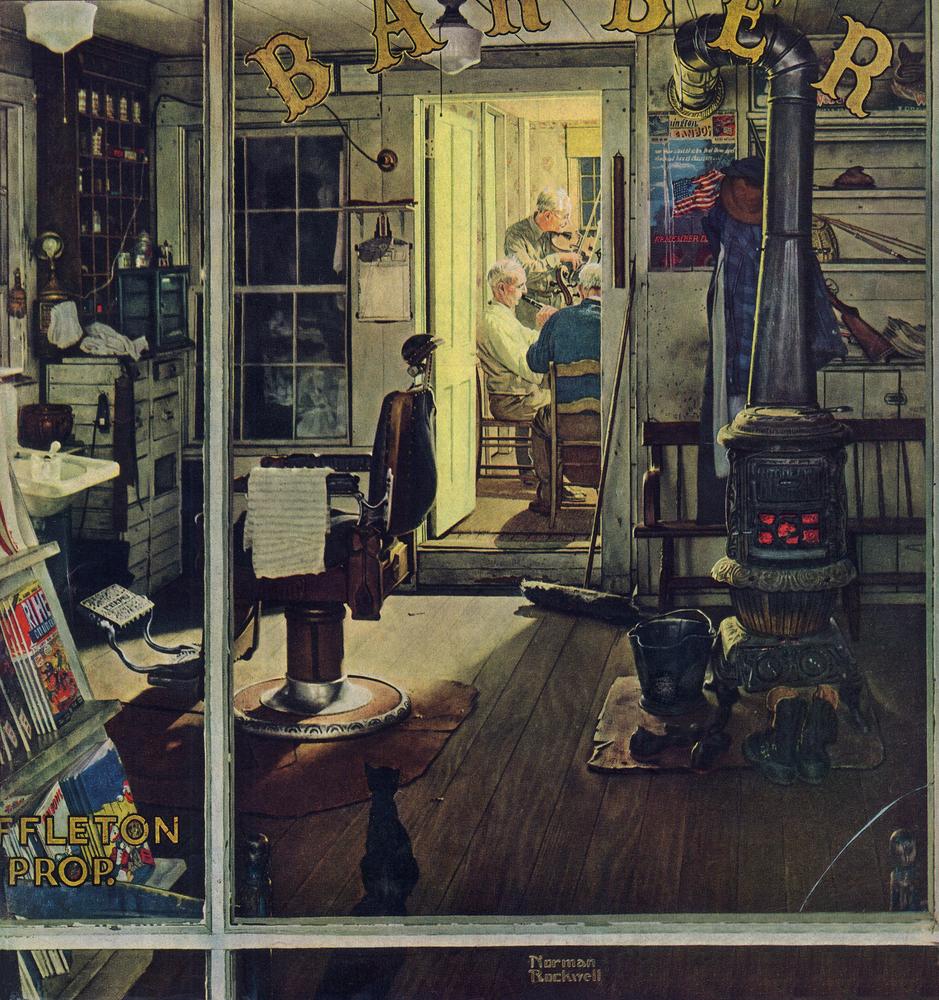

Norman Rockwell’s Shuffleton’s Barbershop, 1950.

After half a year of legal machinations, the Berkshire Museum has won court approval to sell as many as 40 artworks from its collection, including pieces by Alexander Calder, Albert Bierstadt, and Francis Picabia, as well as a Norman Rockwell masterpiece given to the museum by the artist, as part of a deaccessioning plan that has been roundly criticized by museum groups and arts advocates who say it could encourage other museums to sell off works they hold in public trust.

Justice David Lowy of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court said in a six-page ruling issued Thursday that the museum had sufficiently established a need to sell the works, which could raise upwards of $55 million, in order to continue operations. The decision clears the way for at least some of the pieces to go up for sale at Sotheby’s in New York, and for the private sale of the prized Rockwell, which an unnamed institution has agreed to buy in a deal previously approved by the state’s attorney general.

Reactions from those who have been dueling over the plan differed sharply.

“This is great news for the people of Berkshire County and everyone who visits the Berkshire Museum for one-of-a-kind experiences in history, art, and science,” Elizabeth “Buzz” McGraw, the museum’s chairman, said in a statement.

“I think the precedent here is, frankly, disastrous,” Michael Keating, an attorney for some of those who opposed the sale, said in an interview this afternoon. He added, “I’m hopeful that other museums around the state won’t look at this as a license to monetize their collection and avoid the hard work of fundraising.”

Writing on behalf of Save the Art–Save the Museum, a group that has fought the sale, Leslie Ferrin, said that “STA-STM continues to oppose the sale of the Berkshire Museum’s art treasures and its unrestricted use of the resulting funds. We regret the judge’s disregard of the public trust in which the museum held its collections.”

The leadership of the museum, which is based in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, has maintained that it is running a structural deficit and that, without an infusion of cash, it will eventually be forced it to close. Because of diminished fundraising opportunities in the region, museum leaders have said, the ability to sell work is essential. Professional guidelines typically allow art sales only when proceeds are used to acquire other works or, in some cases, maintain a collection.

In October of last year, a variety of plaintiffs had filed suit against the museum to stop the Berkshire Museum’s plan for the sale, arguing that the deaccessioning violated the rights of donors, that the museum was overstating its financial problems, and that, in truth, it needed only a smaller sum to regain financial footing. The museum said it plans to use the money to build from the sales to build an endowment, renovate its building, and pursue what it terms a “New Vision” with an increased focus on science and technology.

The legal battle culminated in a standing-room-only hearing before Judge Lowy last month in Boston. At that hourlong hearing, lawyers for some of those plaintiffs made a last-ditch attempt to scuttle an agreement reached between the state’s attorney general, Maura Healey, and the museum that would allow the sales to proceed largely as planned.

After an investigation of the museum’s plan and its finances, the attorney general’s office said in initial filings in late October that it had “significant questions and concerns” about the plan, and stood by that position as it continued to investigate into January, but in February joined with the museum to ask the Supreme Court to approve a deal that would allow the sale to proceed, with a few restrictions. Part of the deal involves the sale of the major Rockwell—Shuffleton’s Barbershop, from 1950—to an as-yet-undisclosed institution that has promised to keep the painting on view to the public after first presenting it for a stretch at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Emily Snyder, the attorney general’s spokesperson, said in a statement, “We are pleased that today’s decision will help to ensure that the Berkshire Museum can continue to fulfill its broad mission for Pittsfield, Berkshire County, and the general public, preserves Shuffleton’s Barbershop for public view, and reaffirms the attorney general’s role in protecting charitable missions and restrictions.”

With legal hurdles cleared, the auctions can proceed. While dates for prospective sales have not yet been released, at last month’s hearing, the museum’s lead attorney, William F. Lee, said that the plan would need to be approved by April 6 in order for the first works to be sold in the spring. Sotheby’s, which was blocked from selling the works by a last-minute injunction issued by the Massachusetts Appeals Court last November, said in a statement, “We are very pleased that the court approved the agreement reached between the Berkshire Museum and the Massachusetts Attorney General. We look forward to working with the museum to ensure a bright future for the people of Pittsfield and Western Massachusetts.”

The Association of Art Museum Directors said in a statement that the decision “to approve the Berkshire Museum’s planned art sales addresses outstanding legal questions. It does not resolve the violations of ethical and professional standards that will occur when the museum’s plans are implemented.” While thanking the attorney general’s office for its “diligence in examining the public trust and donor intent issues raised,” it said that it will consider “censure and/or sanctions” against the museum in response to any sales that result in funds being put toward operations or endowments.

The agreement between the attorney general’s office and the museum calls for works to be sold in three tranches. If the target $55 million figure is reached before one of the later tranches is put up for sale, later tranches would not be sold. Opponents of the sale have argued that, because the museum is able to structure those tranches, the stipulation does not represent a substantive restriction.

Since the agreement was reached, those opposed to the sell-off have criticized the attorney general’s office for not working to block the move or require changes to the board of the museum, on the grounds that its members were not fulfilling their fiduciary duties. In court last month, Nicholas O’Donnell, an attorney for one group of plaintiffs aligned against the deal, said that the deal “would hand the keys right back to the driver who crashed the car.”

In his ruling, Judge Lowy wrote of those who have fought the sale, “There is no question that [they] care about the museum and the future of art and culture in the Berkshires.” He added, “This court acknowledges those legitimate concerns.” But, he continued, the attorney general, who has oversight of charitable organizations in Massachusetts, had conducted an investigation and reached a conclusion. “She is the attorney for the people, including those who now oppose the sale,” Lowy wrote.

O’Donnell said of today’s development, “The decision makes it more clear than ever that the office of the attorney general’s abrupt and unexplained about-face less than three weeks after forcefully and accurately denouncing the trustees’ fiduciary lapses played an overwhelming role in the outcome. It is a sad day both for the people of Massachusetts and the true custodians working tirelessly to preserve and protect our local and national heritage throughout America.”

Asked about the attorney general’s apparent shift, Keating, the lawyer for the other group of plaintiffs, said, “It’s a mystery to me. The attorney general was as concerned about all the things we were concerned about throughout this process. It was quite inexplicable to me and still is. But once they changed their view, it made it extremely difficult for us to upset that decision, as is clear from Judge Lowy’s decision.”

Keating said that his clients were “disappointed in the judge’s decision. Our clients feel we had raised questions that were very important to raise, both for the citizens of Berkshire County and for the art world in general. We wish the court had decided the matter differently, but the court has spoken and we have to respect that decision.”

“Our clients have always wanted the museum to be successful,” Keating added. “We hope now that they will be successful, considering the enormous cost that will be incurred by the sale of this art.”

[ad_2]

Source link