[ad_1]

Juan Roberto Diago is part of a new Afro-Cuban cultural movement that seeks to center questions of race and the afterlives of slavery in Cuban discourse. Although his practice has touched on installation and photography, Diago primarily makes paintings that marry abstract form, discarded materials, and African religious references. “Diago: The Pasts of this Afro-Cuban Present” is his first comprehensive survey in the United States. In order to convey the social context in which Diago’s practice has developed, curator Alejandro de la Fuente—a historian at Harvard University, where the exhibition premiered—includes quotes from him on the walls, alongside the works. The quotes are direct and denunciatory: they aim to disabuse viewers of any romantic notions they may hold regarding racial equality in Cuba. There is an unresolved tension, however, between their forceful language and Diago’s often formally well-behaved paintings.

Courtesy Cernuda Arte.

El Hombre Azul (The Blue Man, 2009) depicts, from the shoulders up, a style of abstract, generic figure that, serving an archetypal function, recurs in Diago’s paintings. A seam runs vertically down the example in El Hombre Azul, reading as a stitched laceration—a metaphor for the bodily and psychic wounding that black people have experienced since they arrived in the New World. The same type of figure appears in Rostro Sin Nombre (Nameless Face, 2019), but here is rendered on a quilt of small squares of canvas with frayed edges. The geometric background forces the painting’s figural and gestural elements into refined mosaic designs.

The works that fare best in the show’s exchange between combative language and graceful artifacts are those that use the metaphor of the pictorial surface as skin. In Aché Pa’ los Míos (Blessings for My Friends, 1999), a web of white cotton and burlap scraps protrudes like a tangle of scar tissue from the roughly treated—torn in places—burlap ground, heightening our awareness of the painting’s materiality. We are led to consider the historical echoes—“the pasts of this Afro-Cuban present”—that reverberate in the painting and to consider the role of burlap and cotton in plantation economies and their afterlives.

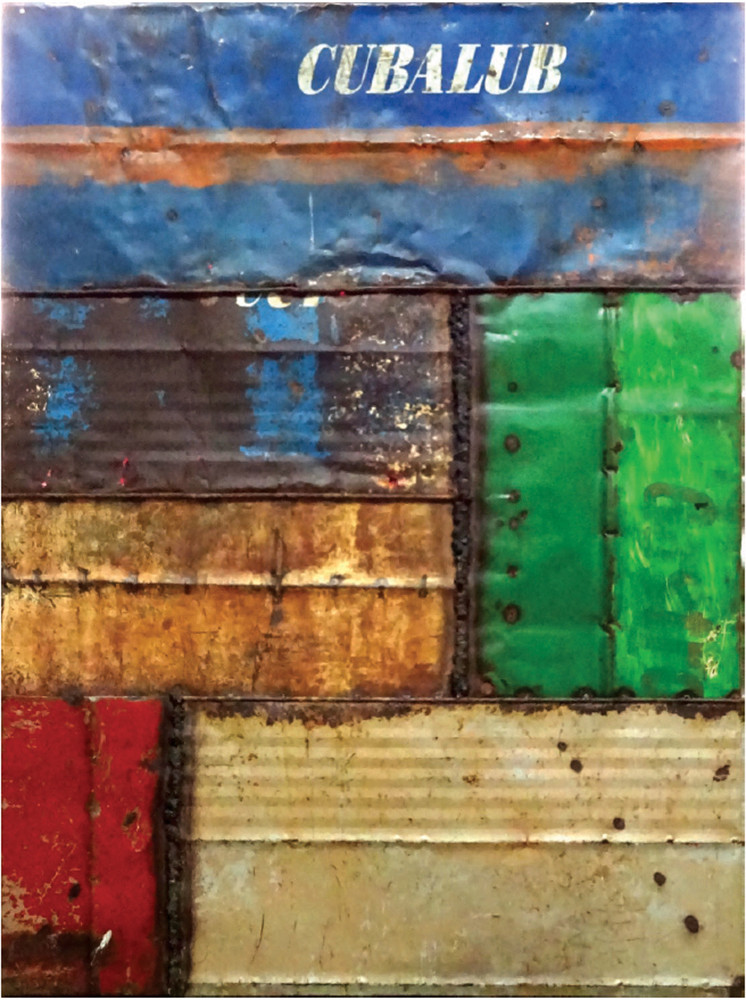

In “Variaciones de Oggun” (Oggun’s Variations, 2013), a series of assemblage-paintings whose name refers to the god of metals and war in a number of Afro-Caribbean religions, Diago welds together pieces of steel from fifty-five-gallon drums to produce gallant geometric compositions. Although he intends the “poor” material to allude to precarious living conditions, to shantytowns and informal economies, it is only the works’ suturing marks—which read as keloid scars—that interfere with a purely formal reading. These largely elegant paintings, sticking close to human scale, are unable to generate a sense of physical discomfort that could match the conceptual heft of their subject matter.

El Poder no se Regala se Lucha (Power Is Not Given but Conquered, 2009), which depicts a bowl or cooking pot floating between the words of the title, consists of thirty small panels. The corners of the panels have been removed to reveal stretcher bars in the form of hand-carved dowels. The artist has discussed the role of the tourist industry in Cuba, which exploded after the fall of the Berlin Wall. These dowels resemble kitschy materials found in tourist traps, such as the caning seen in tiki bars and on chairs in faux-traditional restaurants. The rise of the tourist industry—which favors people with certain phenotypes and skin tones for jobs and other opportunities—reactivated racializing and discriminatory behaviors that had supposedly vanished with the revolutionary process, and enlarged economic disparity along the color line. When Diago’s paintings break the traditional structure of the medium, they assume in a subtle but piercing way the explosive candor of his discourse and its desire to rip through the language and fantastical declarations with which race is treated (or not treated) in Cuba.

This article appears under the title “Juan Roberto Diago” in the January 2020 issue, p. 83.

[ad_2]

Source link