[ad_1]

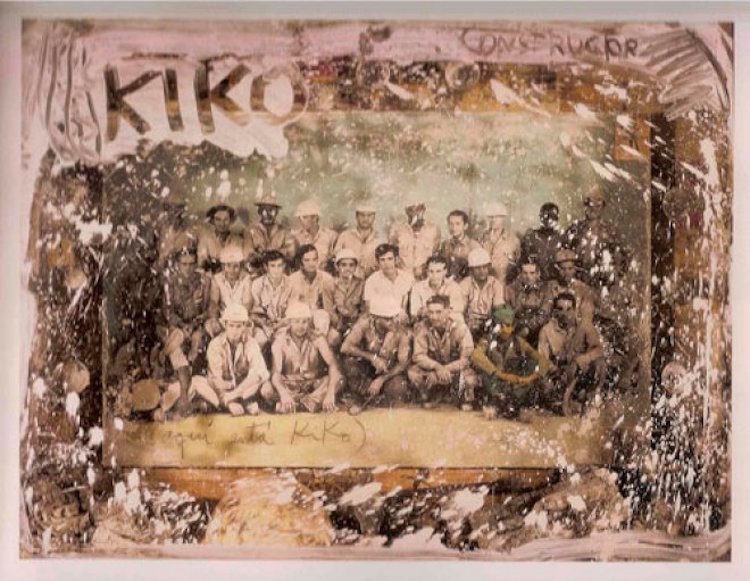

Courtesy Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana

From a childhood in Cienfuegos, Leandro Soto (b. 1956) has gone on to a career that has taken him, as an interdisciplinary artist and teacher, to many parts of the world. A key figure in early contemporary Cuban art, Soto was among the participants in the groundbreaking Volumen Uno exhibition of 1981. Crónicas visuales, currently on view at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana, traces Soto’s career and his abiding interest in indigenous cultures of the world.

From his home in Barbados, Soto talked with Cuban Art News via email about Crónicas visuales, his life experiences, and his art.

Let’s start with a quick overview of your training. How did you begin?

I started my art studies in Cienfuegos, a city where people place great importance on the visual arts and theater, music, and literature. When I was 11 years old I entered the Escuela de Iniciación Artística (Elementary School for Art). At 16, I was accepted to the Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA) in Havana.

There, I studied painting and engraving with good Cuban artists such as Antonia Eiríz and Antonio Vidal, among others. Since the school had other disciplines, such as ballet, theater, modern dance, and music, I had a direct relationship with other forms of creative expression and attended those classes in my spare time.

Courtesy Leandro Soto

Among my classmates in painting were Gustavo Pérez Monzón and Juan Francisco Elso Padilla, who graduated with me in 1976. From there I was sent to Cienfuegos as a set designer at the Teatro Tomás Terry.

I became a volunteer curator in the Galería de Arte, and was in charge of overseeing visual arts for the city’s annual festivals. On the wall at the corner of Prado and San Fernando, there’s still a mural that I painted for some carnavales when I was 20 years old, which has become a symbol of the city.

Thanks to this strong involvement with culture, I was able to present the exhibition Pintura Fresca (Fresh Paint) in the Galería de Arte. It was the predecessor to the famous exhibition Volumen Uno.

At the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA), I was more involved in the performing arts school. I worked as an instructor there from 1982 to 1986. My area was designing costumes and settings for theater productions. At that time, the Escuela de Teatro Nuevo in Latin America was emerging, and I found myself involved in very creative interdisciplinary projects in which the theatrical image—that is, the visual metaphor—was as or more important than the verbal text.

Volumen Uno was a landmark in contemporary Cuban art.

The Volume Uno exhibition was curated by the participating artists themselves. We were very aware that we wanted to open new directions in Cuban art, respecting everyone’s individual approach. In my case, I presented performances, installations, and their documentation: works made in Cienfuegos as Ancestros, El hombre y los estrobos, and Mutable in Avenida Cero (1979).

Courtesy Leandro Soto

At first the exhibition caused controversy, despite being widely visited by the public, and some aesthetic and generational conflicts became evident. That surprised me, because in Cienfuegos, Pintura Frescadid not generate any conflict. The capital of the country was more closed to innovation than a provincial city in 1981!

What are some of the themes that became important in your creative career?

Literature, poetry, and mythology have always been sources of inspiration. For example, my first exhibition was called The story of a man told by his things, which was titled after a text by José Marti.

I used the indigenous mythology and legends of Cienfuegos as themes for a lot of the pieces. In my second solo show, Trastos, I used some furniture—things that had been discarded as old and unusable—to represent the values of another era. The book Paradiso by Lezama Lima was the foundation of this work, especially a piece called La Imago. It was made with an old mirror in which people could no longer see themselves: the viewers were enticed to look within in order to find the missing image.

The story of my own family served as artistic material. Retablo Familar was an exhibition in which that particular narrative became the tale of a Cuban family immersed in economic and political changes, told from the perspective of a child caught up in it.

Courtesy Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana

At a certain point, you became involved in ethnography.

My desire to be an anthropologist and ethnographer hit its peak during my first years in indigenous communities in southern Mexico. The mythology was alive. It was more than simply recovering a story from the past. It was a vision of the world that threw into a crisis all the Eurocentric Marxist training that I learned in Cuba.

In thanks for my acceptance as a member of their communities, in 1988 I created an interdisciplinary art school in a Maya Chontal town in Tabasco. It trained very good artists, who now represent Mexico at the international level. The concept was to turn all the ancestral stories—through which knowledge and collective wisdom were passed on through the generations—into visual images.

Courtesy Leandro Soto

Returning to Cuba after that experience, I went to the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional (National Folkloric Ensemble) to study African dances and to produce a choreographic work dedicated to a black Cuban musician—a 19th-century classical violinist named Brindis de Salas—where the conflict of choosing between Europe and the Caribbean was the main theme.

Tell us about Crónicas visuales, your exhibition at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana.

Crónicas visuales was curated by Dr. Grisel Pujala and Corina Matamoros. The exhibition shows pieces made in different cities and countries worldwide where I’ve spent time. To name a few: Villahermosa, Tabasco and Mérida, Yucatán, in Mexico; Phoenix, Arizona; Buffalo, New York; and South Hadley, Massachusetts, in the United States; Cuzco and Macchu Pichu, Peru; the Ecuadorian Andes; Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago in the insular Caribbean; Panama City, Panama; New Delhi, Bangalore, Mumbai, and Dharamsala, India.

Courtesy Leandro Soto

There is painting, drawing, video, installation work, book art, object art, and performance in the show. The works span 1988 to 2018. It’s like a huge diary, opened to and illustrating my ethnographic and anthropological research, integrated into and by the art world. On the white walls of the gallery there are written texts and travel notes that make this idea clearer.

We Cubans are complex. I grew up in a seaport city, where I listened to languages from all over, and the city itself is a combination of styles, techniques, and materials. Our genetic mix is intense and my physical body is an example of this. Behind this profuse variety is an investigation of what defines la cubanidad—whether it is something formal, thematic, or simply a way of integrating everything.

Photo: Mario Porchetta, courtesy Leandro Soto

Are we still Cuban even though we live far from Cuba? Or does living away define us as Cuban even more? In this exhibition you can see work with themes and visions of the Maya, Inca, Tohono O’odham, and Hopi worlds, as well as Abakuá, Yoruba, Egyptian, and Hindustani, all of which are part of these investigations. They do not result from short, casual trips, but from residencies undertaken to see everyday reality from different perspectives.

What is your impression of Cuban art at this moment? In your opinion, what are some of the challenges facing Cuban artists, on the island and abroad?

Cuban art, past or present, always surprises me because of its technical and conceptual quality. This can be seen in the pavilions of Cuban artists in the Havana Biennial, or in the galleries where young artists continue to maintain high standards. This happens today in Havana as well as in the provinces. That is to say, the discoveries of our generation are still alive.

Courtesy Leandro Soto

The challenge of the Cuban artist can be one of repetitive monologue—discourse should be multiple in content as well as in form. My method has been to move to seemingly alien, distant cultural contexts, and to experiment there with what to do and how to make art, using local materials, techniques, and content—without losing contact with the island.

Lo cubano is something open, in constant formulation that we carry with us everywhere.

Leandro Soto: Crónicas visuales remains on view at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana through May 14.

Photo: Mario Porchetta, courtesy marioporchetta.com

[ad_2]

Source link