[ad_1]

An influential and prolific photographer, Alfred Stieglitz produced thousands of pictures throughout his career, covering numerous themes that captured different periods of a rapid transition in American society. In addition to his photography work, he was a vital force in the development of modern photography and modern art in general in America, working as an art dealer, exhibition organizer, publisher and editor. He published the periodical Camera Work, formed the exhibition society the Photo-Secession and ran a series of influential galleries, most notably the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, better known as the 291 Gallery.

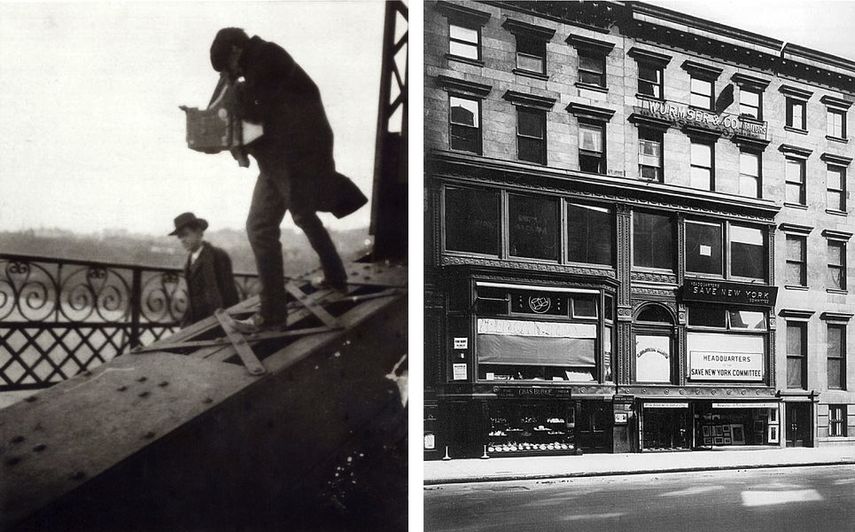

This influential gallery, which operated at 291 Fifth Avenue in New York from 1905 to 1917, helped bring art photography to the same stature as painting and sculpture, but also introduced some of the most avant-garde European artists of the time to America and fostered the country’s own modernist figures.

The 291 Gallery

At an early meeting of the Photographic Society of London established in 1853, one of the members described photography as “too literal to compete with works of art” because it was unable to “elevate the imagination”. Fast forward to the early years of the 20th century, when the medium’s place in the world of fine art was still very indefinite. Photographers were not considered “real” artists and even major photographic exhibitions were judged by painters and sculptors.

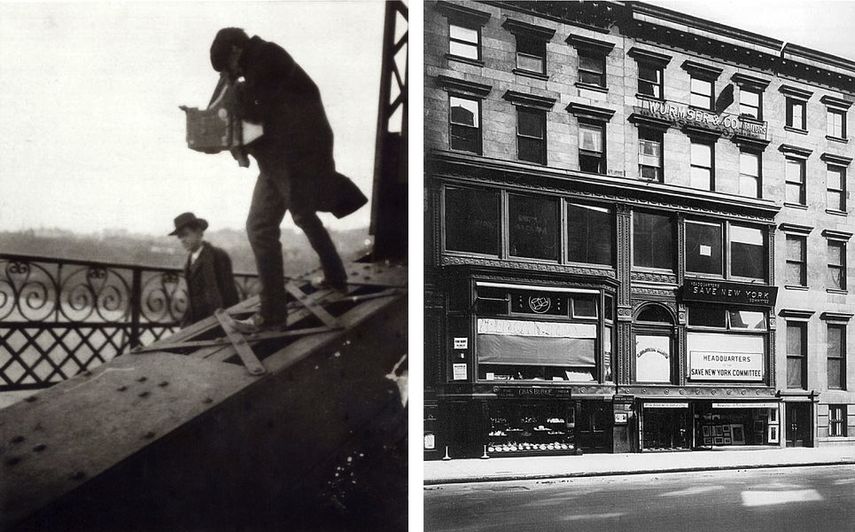

Insistent that photography warranted a place among the fine arts, Alfred Stieglitz was in search of the best forum to present it to the public. He founded the Photo-Secessionist movement that sought to promote photography as fine art in general and photographic Pictorialism in particular and launched Camera Work magazine as its voice. Urged by his friend Edward Steichen, he signed a one-year lease for three small rooms across Steichen’s apartment to create an exhibition space called the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, commonly known as 291 Gallery after its address at Fifth Avenue. They wanted to use the space the most effectively, not only as a gallery but also as an educational facility for artists and photographers and as a meeting place for art lovers.

The gallery was formally opened on November 24th, 1905 with an exhibition of one hundred prints by Photo-Secession members, all selected by Stieglitz. Over the next few weeks, it attracted hundreds of New Yorkers.

The Influence on Photography and Modern Art

Throughout the first year, the 291 Gallery hosted a range of photographic exhibitions. These included the exhibition of French photographers, including Robert Demachy, Constant Puyo and René Le Bégue, a two-person show of the works of Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White, a show of works by British photographers, early prints by Steichen, a show devoted to German and Austrian photographers, and another display of prints by members of the Photo-Secession. The gallery soon became a destination for intellectuals and artists, who engaged in freewheeling discussions in addition to viewing the art on display.

After this successful year, the fellow photographer Joseph Keily wrote:

Today in America the real battle for the recognition of pictorial photography is over. The chief purpose for which the Photo-Secession was established has been accomplished – the serious recognition of photography as an additional medium of pictorial expression.

In 1907, Stieglitz decided to shake things up by mounting the first non-photography show at the gallery. Although it was a major success, the gallery continued with photographic exhibitions for the rest of the year, including those by such photographers as Adolf de Meyer, Alvin Langdon Coburn and members of the Photo-Secession. In 1908, the gallery hosted its second non-photographic show Drawings by Auguste Rodin, which first introduced the artist’s works on paper to the United States.

Due to the increase in rent, the gallery soon had to close its original location, but opened next door with the financial help of Stieglitz’s acquaintance, Paul Haviland. Stieglitz and Haviland decided to officially adopt the name 291 instead of the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, wanting the new space to be about more than photography.

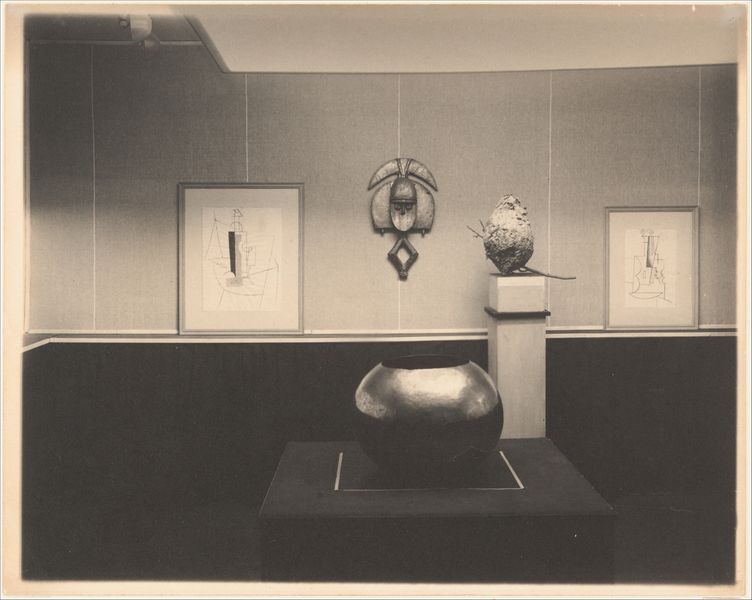

Originally an outlet for exhibiting work by Photo-Secessionist photographers, the gallery soon became a preeminent center for the exhibition of modern European and American artists. It became the first venue in America to show Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, and Pablo Picasso. It also showed works by artists such as Constantin Brancusi, Francis Picabia, John Marin, Max Weber, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Marius de Zayas and Georgia O’Keeffe, who later became Stieglitz’s wife.

Virtually no other galleries in the United States were showing works with such abstract and dynamic content at the time, introducing the public to the individuals who are now regarded to have been at the forefront of modern art. From 1909 until it closed in 1917, The 291 Gallery featured only six shows of photography out of a total of 61 exhibitions held.

The Legacy of 291 Gallery

Defeated by financial woes caused by the war, and his own uncertainty about his role in promoting modern art, caused by the emergence of the Armory Show, Stieglitz closed the gallery in June 1917, only two months after the United States declared war on Germany. Over the next eight years, he focused on his own photography and organized exhibitions of art and photography at other venues.

When Stieglitz first started introducing works of modern art, the idea was to test photography against the “most alive work” being done in other media. He hoped that through exhibiting modern art as well as photography the value of each as a means of art could be realized. In a 1907 publication of Camera Work, Stieglitz wrote that his non-photographic exhibitions sought to bring about the understanding of “what photography really means”:

Men like Matisse and Picasso and a few others are giants. Their vision is anti photographic… It is this anti photography in their mental attitude and in their work that I am using in order to emphasize [sic] the meaning of photography.

Before Stieglitz’s efforts, photographs were purely understood as historical records. Through his own photographic works, he helped define the greater Pictorialist project and set a firm aesthetic example for his contemporaries. The influence of Camera Work magazine and 291 gallery was immense, providing legitimacy of photography in the United States and allowing photographers like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston to become household names.

Editors’ Tip: TruthBeauty: Pictorialism and the Photograph as Art, 1845-1945

The hauntingly beautiful works of the Pictorialist movement are among the most spectacular photographs ever created. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Pictorialist artists sought to elevate photography— until then seen largely as a scientific tool for documentation—to an art form equal to painting. Adopting a soft-focus approach and utilizing dramatic effects of light, richly coloured tones and bold technical experimentation, they opened up a new world of vision expression in photography. More than a hundred years later, their aesthetic remains highly influential.

Featured image: Frank Eugene – Eugene, Stieglitz, Kühn and Steichen Admiring the Work of Eugene, 1907, platinum print, Yale Collection of American Literature. All images Creative Commons.

[ad_2]

Source link