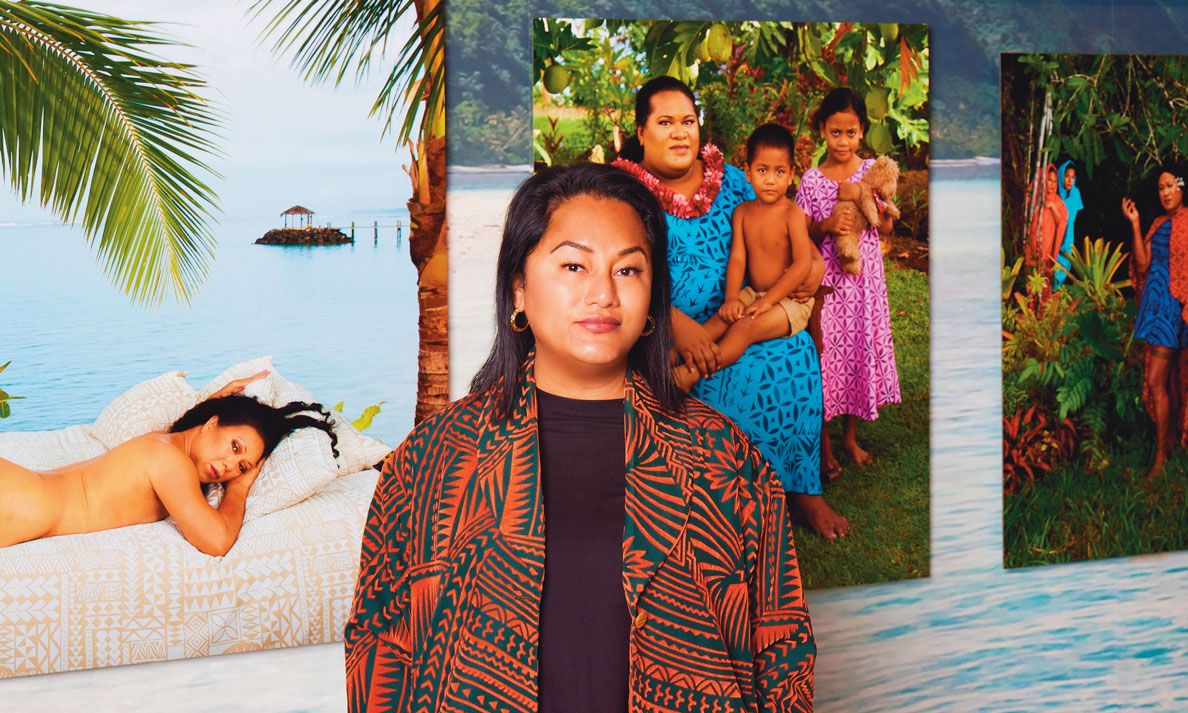

Yuki Kihara Photo: Luke Walker

The Japanese-Samoan artist Yuki Kihara is perhaps best known for work that questions representations of the Pacific Islands and its people popularised by Western artists and colonial-era photographers. Often using historical images as source material, she reworks familiar depictions of First Nations people, using subtle interventions to displace traditional readings and empower her subjects.

For Kihara’s latest body of work, Paradise Camp, she turned her attention to Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings made between 1891 and 1903. Kihara’s series, which is being reprised this month at Sydney’s Powerhouse Ultimo after its debut in the New Zealand pavilion at the Venice Biennale last year, recreates the French Post-Impressionist’s paintings as photographs. Kihara casts members of the fa’afafine community, Samoa’s culturally recognised third gender, as the main subjects.

Yuki Kihara's Si‘ou alofa Maria: Hail Mary (After Gauguin) (2020) from the Paradise Camp series Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries; Aotearoa New Zealand

The Art Newspaper: Paradise Camp had a long gestation period. How did an encounter with Gauguin’s paintings in New York become a catalyst for this project?

Yuki Kihara: I was very fortunate to have a solo exhibition [Shigeyuki Kihara: Living Photographs] at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2008. I basically had staff access to the museum. You know that movie Night at the Museum? It was pretty much like that. I happened to stumble into Impressionist movements and Post-Impressionism and saw a painting by Paul Gauguin. Prior to arriving at the Met, I only saw Gauguin’s paintings on a T-shirt, on a coffee mug, paraphernalia, tea towels and all these kinds of things. I was actually very intrigued that people make such a big fuss about this. The paintings reminded me of photographs of people and places in Samoa, including members of the fa’afafine community, which is the Indigenous third-gender community. And then I began to read up about Paul Gauguin’s life in French Polynesia.

What did you uncover?

I found visual evidence [suggesting] that although Gauguin never stepped foot in Samoa, he may have used photographs of people and places in Samoa to develop his major paintings. The silhouette of the man in the Three Tahitians painting was very similar to the photograph of a Samoan man that was photographed by the New Zealand colonial photographer Thomas Andrew, whose postcards were actively circulated in the tourism market all around the country.

In the visitor book of the Auckland Art Gallery in 1895 there was a signature of Paul Gauguin. So I think he may have collected these photographs, taken them back to his studio in Tahiti and used them as his foundational reference, which resulted in the development of his major paintings.

Kihara's Gauguin Landscapes (2023) Photo: Zan Wimberley

You identify as fa’afafine. Can you tell us about this community and why you chose them as models for this work?

Whenever I make work, I always think about who I want to empower. I think that for too long we [the fa’afafine] have been sidelined, marginalised, exploited, undervalued. In Samoa there are four culturally recognised genders. There’s tane, which is a word to describe cisgender men; there’s fafine, which is a cisgender woman; and there is fa’afafine, meaning in the manner of a woman, that is used to describe those like myself: biologically assigned male at birth who express their gender in a feminine way. And we also have fa’atama, which is in the manner of a man, used to describe those assigned female at birth, who express their gender in a masculine way. However, the fa’afafine and fa’atama communities [are] not legally recognised and the reason why we’re not legally recognised is because [Samoa] went through two colonialisms.

It was really fortuitous that Paradise Camp ended up at Venice and it’s now touring around the world before it actually arrives in Samoa, because without Venice and any kind of critical attention around it, I don’t think anybody would care for the kinds of things that I’m interested in talking about.

Paradise Camp was not originally conceived for the Venice Biennale. How did the opportunity to represent New Zealand change the project?

Paradise Camp had been in the making for ten years and during that time I did my own recce. When I did the recce and came up with the budget to do it properly, because it was so big and so ambitious, I realised that the only kind of funding that was available was Creative New Zealand’s budget for the Venice Biennale. I thought, if that’s the budget that can make it happen, if it’s for Venice, then so be it.

Of the 12 photographs in Paradise Camp, 11 were taken at various locations across Samoa. What was it like working on location with your cast and crew?

Paradise Camp employed 100 people locally on the island. It also required extensive consultation with traditional landowners, because it meant people outside of their villages coming in with van loads of people to set up a tent and lights and all these kinds of things. So it was really important that the traditional landowners were well informed and briefed about the kinds of logistics required for my production team to go into their village to do a variety of shooting. We also needed to consult with a resort to use it as our production headquarters, not only for our crew, but to also host the talent. So although it was a photography production, I used the methodology of filmmaking militantly in order to make sure that everybody was playing their part.

An installation view showing Kihara's Fonofono o le nuanua: Patches of the rainbow (After Gauguin) (2020) Photo: Zan Wimberley

Why did you choose the title?

When we think of paradise, the first thing that people think about is the Pacific Islands, usually a newly married heterosexual couple, holding hands wearing white, walking alongside the beach at dusk, while a native is waiting around the corner ready to serve cocktails. If I was to dissect this touristic representation of the Pacific, for me it’s like a direct replica of Adam and Eve: they’re both white, they’re both cisgender and the snake serpent is the native holding the cocktail. I wanted to deploy the aesthetic of camp to challenge this Western heteronormative idea of paradise. So Paradise Camp is essentially the fa’afafine version of what our paradise could be, which is inclusive, diverse and sensitive to the changes of nature and the environment.

Paradise Camp includes a talk show, First Impressions, featuring members of the fa’afafine and fa’atama communities critiquing the work of Gauguin. How did that come about?

I actually made First Impressions before I made the photographs. There was a major Gauguin blockbuster presented at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the curator wanted to include Indigenous voices, and they approached me. And given that we have very limited space for showing contemporary art on the islands, I thought of a TV show because at least my family can watch it. So it was made for TV and my mum did the catering, and my relatives made the set. It was fun, it

was a real community effort.

The magic of being part of the fa’afafine community is that when we all get together our gossip sessions are no holds barred, it’s very trashy because we just like to giggle and have fun. I wanted to capture some of the private conversation that we have amongst ourselves in the TV show. When you ask people from the Pacific region who Paul Gauguin is, nobody would know. What I find ironic is that this figure that is seen as anchored in the development of Modernism doesn’t have any relevance to the Pacific community. What First Impressions does is provide an insight into what Samoan fa’afafine think about Paul Gauguin’s work; it actually becomes a commentary about themselves and their lives, and that’s what makes it interesting.

Kihara's Nafea e te fa‘aipoipo? When will you marry? (After Gauguin) (2020) from the Paradise Camp series. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries; Aotearoa New Zealand

Born: 1975 Apia, Samoa

Lives: Apia, Samoa

Education: Massey University

(formerly Wellington Polytechnic),

New Zealand

Key shows: 2023 Gwangju Biennale (forthcoming); 2023 Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney (solo exhibition); 2022 New Zealand Pavilion, Venice Biennale; 2022 Aichi Triennale; 2018 Bangkok Art Biennale; 2017 Honolulu Biennial; 2014 Daegu Photo Biennale; 2013 Sakahàn Quinquennial; 2015 Asia Pacific Triennial; 2008 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (solo exhibition); 2002 Asia Pacific Triennial

Represented by: Milford Galleries, New Zealand

• Paradise Camp by Yuki Kihara, Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney, 24 March-December 2023