Alison (Tennessee): What can the House do to enforce its subpoenas if and when witnesses like Rudy Giuliani and Mike Pompeo refuse to comply?

The House has three traditional legal avenues, all of them problematic.

First, the House theoretically has its own inherent enforcement power, but that has essentially gone

dormant after nearly a century of non-use. The House does not have a police force capable of making arrests — the

sergeant-at-arms is primarily a security force — or a functioning

jail facility.

Second, the House can refer a contempt case for criminal prosecution. But that referral would go to Barr’s Justice Department, and it is very unlikely he would bring criminal charges given his established

pattern of protecting Trump and those around him.

Third, the House can file a civil lawsuit in court. But this will take months to resolve, and the House simply does not have the luxury of time to litigate.

But the House is getting creative — and tough. Schiff has notified subpoena recipients that he will draw an “

adverse inference” if they do not comply. In other words, he will assume their non-response means the testimony would have been damaging to those accused. Second, the House has the ability to bring an article of impeachment for

obstruction of Congress; indeed, one of the draft articles of impeachment against Nixon was for obstruction of Congress.

Carlos (Florida): Can Congress impeach Trump based solely on written documents like the whistleblower’s complaint or special counsel Robert Mueller’s report?

Yes.

Article I of the Constitution broadly grants the House the “sole power of impeachment,” but says nothing whatsoever about how an impeachment proceeding must be conducted, or what type and quantum of evidence is necessary to impeach. This is different from federal criminal trials, which are governed by specific rules of procedure, rules of evidence and the requirement that the prosecutor prove a defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

In fact, when the House

impeached President Bill Clinton in 1998, it did so solely on the basis of Independent Counsel Ken Starr’s written report and supporting evidence. The House called no live fact witnesses and

introduced no additional evidence.

That said, the House will conduct its own investigation into the Ukraine scandal in the coming weeks and months. Pelosi has announced that the

six major House committees — Judiciary, Intelligence, Ways and Means, Oversight, Financial Services and Foreign Affairs — will each investigate and then forward recommendations to the Judiciary Committee, which in turn will decide whether to recommend articles of impeachment (and if so, which ones) for a vote by the full House.

Such investigation seems necessary here because many of the key questions around the Ukraine scandal

remain unanswered. So, the House’s investigation will be crucial to determining whether an adequate basis exists for impeachment.

Kenneth (Maryland): Article II Section 2 of the Constitution provides that the president “shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” Now that House Democrats initiated impeachment proceedings against Trump, can he still issue pardons?

Yes. The President can issue pardons in criminal cases right up until the moment he leaves office. In fact, many presidents

have issued pardons in their final days and hours in office, likely because pardons tend to be politically unpopular.

While the President has the constitutional power to pardon federal crimes — “offenses against the United States” — he cannot issue pardons for impeachment. So, if the President or any other federal official is impeached by the House and then convicted by the Senate, there is nothing he (or anyone else) can do to reverse it. There is no way to appeal or undo an impeachment.

Vikki (Illinois): Could the House conduct a formal impeachment investigation and then vote to censure the President, rather than impeaching and sending it to the Republican-controlled Senate for trial?

Constitutional law scholar Laurence Tribe

has proposed a similar procedure designed to create a formal record of Trump’s conduct in the Democratic-controlled House without sending the matter to the Republican-controlled Senate for what many see as an inevitable party-line vote of acquittal.

Under Tribe’s proposal, the House would hold an impeachment investigation, affording Trump the right to mount a defense. The House would then vote on a resolution proclaiming the President impeachable — which Tribe calls “far stronger than a mere censure” — but would not forward the matter to the Senate for a formal vote on removal from office.

Tribe’s proposal has some merit. It would promote public understanding of Trump’s conduct and create an important historical record. As Tribe writes, the House would act “consistent with its overriding obligation to establish that no president is above the law … without setting the dangerous precedent that there are no limits to what a corrupt president can get away with as long as he has a compliant Senate to back him.”

I see two arguments against Tribe’s approach. First, it is an end-run around the process set forth in the Constitution: the House votes to impeach, then the Senate holds a trial and votes either to acquit or to convict and remove from office. Second, Tribe’s approach is more sizzle than steak. While the House would go through the motions, the end result (at most) would be a sternly-worded resolution condemning the President, but without actual penalty (such as removal from office).

Zhiliang (Chile): During the impeachment investigation, will the House investigate only the Ukraine affair, or other potential offenses by Trump as well?

Article I of the

Constitution broadly grants the House “the sole power of impeachment” without imposing any limits on scope or (as discussed in the next question) timing. Thus, it is entirely up to the House to define the scope of its investigation and, eventually, any Articles of Impeachment. While the

Ukraine scandal will surely be the primary focus of this inquiry, House Democrats have no shortage of other menu items to consider: the

findings of special counsel Robert Mueller on Russian election interference and obstruction of justice,

emoluments and

self-enrichment, and

obstruction of Congress, to name three.

For now, Speaker Nancy Pelosi is keeping a wide lens on the House’s investigations. She has announced that

six major House committees — Judiciary, Intelligence, Ways and Means, Oversight, Financial Services and Foreign Affairs — will each investigate and then forward recommendations to the Judiciary Committee, which in turn will decide whether to recommend Articles of Impeachment (and if so, which ones) for a vote by the full House.

While Pelosi has directed broad investigations by the committees, she also told Democrats privately that she intends ultimately to

focus narrowly on the Ukraine scandal in Articles of Impeachment. This is a smart tactical move by Pelosi: she keeps her options open, keeps various House committees in her caucus engaged, and maintains the appearance of considering all options. Yet if Pelosi’s strategy holds and eventual Articles of Impeachment focus solely on Ukraine, she will play her strongest hand without diverting attention by including more complex, potentially distracting matters.

John (Illinois): How long does the impeachment process take?

Legally, there is no time limit on the impeachment process. This is in contrast to the criminal justice process, which limits the amount of time that can pass between the commission of a crime and indictment (the “statute of limitations”) and the time between indictment and trial (“speedy trial” rules).

Practically and politically, however, Congress knows the clock is ticking. The current Congress sits until January 2021, so any impeachment proceedings must and certainly will conclude by then (though the next Congress can resume any pending inquiry if it sees fit). And, of course, a presidential election looms in November 2020.

As the election draws closer, impeachment proceedings will become increasingly contentious and politically fraught. House leaders understand the need to move quickly here.

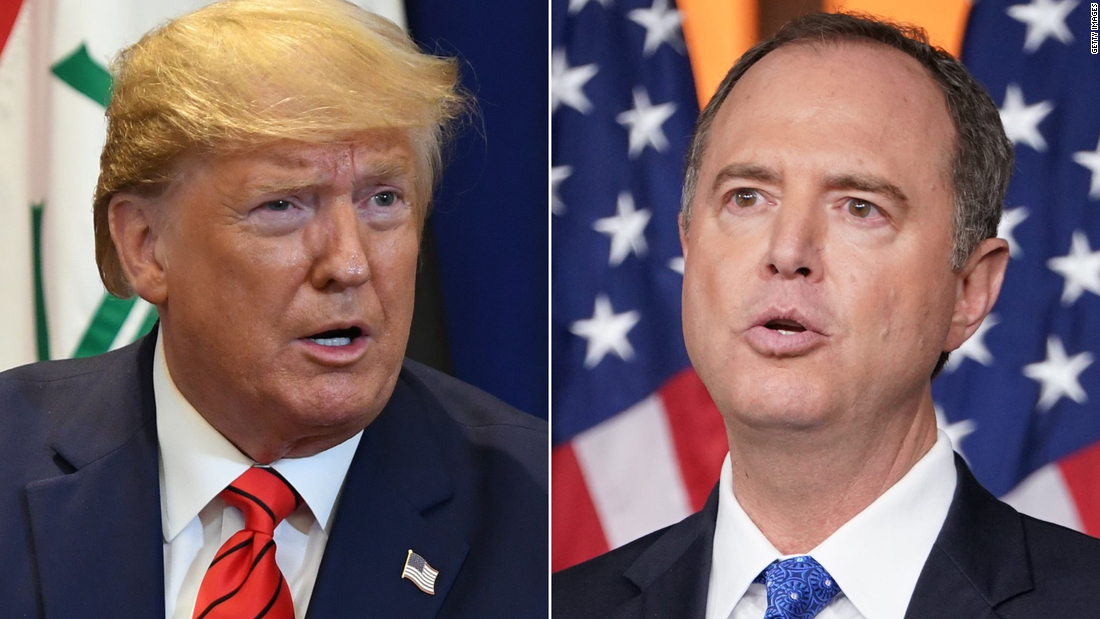

Pelosi and Chair of the House Intelligence Committee

Adam Schiff have both vowed to move “expeditiously,” and Chair of the House Judiciary Committee Jerry Nadler has

declared “full speed ahead.”

The

Bill Clinton impeachment timeline provides a useful guide. The House opened an official impeachment inquiry in October 1998 and impeached Clinton in December 1998. The Senate then held Clinton’s trial, which resulted in acquittal, in January and February 1999. It seems realistic for Congress now to replicate the fairly quick pace of proceedings in the Clinton case.

But right now Congress is on an even tighter political timeline: In the Clinton case, the next presidential election (in November 2000) was just under two years away, whereas now the next presidential election (in November 2020) is just under one year away. Time will be of the essence for Democrats.

Stevens (Virginia): Must impeachment be based on a statutory crime?

No. Congress certainly can — and perhaps must — impeach if the President has committed a crime. But even if Trump’s conduct dodges the statutory raindrops and doesn’t quite meet the definition of a federal crime, impeachment at its core is a remedy for abuse of constitutional power.

The Constitution

prescribes impeachment for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” But the term “high crimes and misdemeanors” is not defined anywhere in the Constitution or statute law, and appears to be

drawn from English parliamentary practice, which provided for impeachment for crimes or for conduct beyond the reach of established criminal law.

Our own precedent supports the notion that a crime is not necessary for impeachment. President Andrew Johnson was

impeached by the House (and then acquitted by the Senate) for firing a Secretary of War — certainly not a criminal act. Drafted

articles of impeachment against President Richard Nixon included abuse of power and misuse of public office, while one of the proposed articles of impeachment against President Bill Clinton (voted down by the full House) related to

abuse of power for non-criminal conduct.

Sean (Wisconsin): Can Senate Majority Leader McConnell refuse to hold a trial in the Senate, if the House of Representatives votes for Articles of Impeachment?

Sen. Mitch McConnell has

stated that if the House impeaches Trump, he “has no choice” but to hold a trial in the Senate. But it remains to be seen if that promise holds as the investigation continues, especially if partisan rancor continues to build.

Some observers have

theorized that McConnell could indeed decide not to hold a trial. The

Constitution broadly grants the Senate the “sole power to try all impeachments,” and, the argument goes, McConnell could simply construe that broad power to include the power not to proceed.

But the fallout from such a decision would be dramatic, legally and politically. Legally, I’d expect Democrats to challenge a decision not to hold a trial as a violation of the Constitution. And politically, it would be an enormously risky move for McConnell to give the impression that he is trying to short-circuit the Constitutional process, and to leave the House’s Articles of Impeachment essentially hanging as a series of unrebutted accusations.

McConnell does, however, have broad discretion over how a Senate trial would be held. The

Constitution essentially specifies only two particular procedures: that the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (in this case, John Roberts) must preside, and that a two-thirds vote is necessary for conviction and removal. Beyond that, it will be almost entirely up to McConnell to fill in the procedural blanks.

Larry (California): If the President is impeached by the House and found guilty by the Senate, is he or she prevented from running for office in the future? Could Trump be impeached and removed from office and then run again in 2020?

The Constitution

states that a judgment of impeachment results in “removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States.” Thus, on its face, the Constitution appears to stipulate that if a person is impeached by the House, convicted by the Senate and removed from office, he also can be disqualified from holding office in the future.

But some legal scholars

have argued that the Senate must vote separately on (1) removal from office and (2) disqualification from holding future office. Looking at

historical precedent, the Senate has at least twice voted to remove federal judges, and then separately voted on whether to disqualify the judges from holding office in the future. And while a two-thirds vote of the Senate is constitutionally required for removal, the Senate has used a lower simple-majority vote standard in

prior cases of disqualification.

So, if the Senate did vote to convict and remove the President, it likely would also vote separately on whether to bar him from holding office again in the future.

Steven (New Jersey): Is it true that if Congress brings an impeachment case to the Senate, and the Senate delivers a “not guilty” verdict, then upon leaving office, Trump cannot be prosecuted criminally because of double jeopardy?

No, that is not true — although Pelosi once implied it might be when she

reportedly told House Democrats, “I don’t want to see (Trump) impeached. I want to see him in prison.”

In fact, impeachment and criminal prosecution are two entirely distinct processes, serving different purposes. Impeachment is a political process prescribed by the

Constitution to remove the president or other federal officials from office, separate and apart from criminal charges. A president can be impeached by the House and convicted by the Senate but then never charged criminally.

Conversely, a president can be impeached by the House, acquitted (found not guilty) by the Senate, and then later indicted after leaving office. Either way, double jeopardy would not prevent prosecution because impeachment is not a criminal process, and hence does not qualify as a “first” jeopardy, so to speak.

Editor’s note: In an earlier version, the passage citing “treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors” incorrectly omitted the word “other.”