[ad_1]

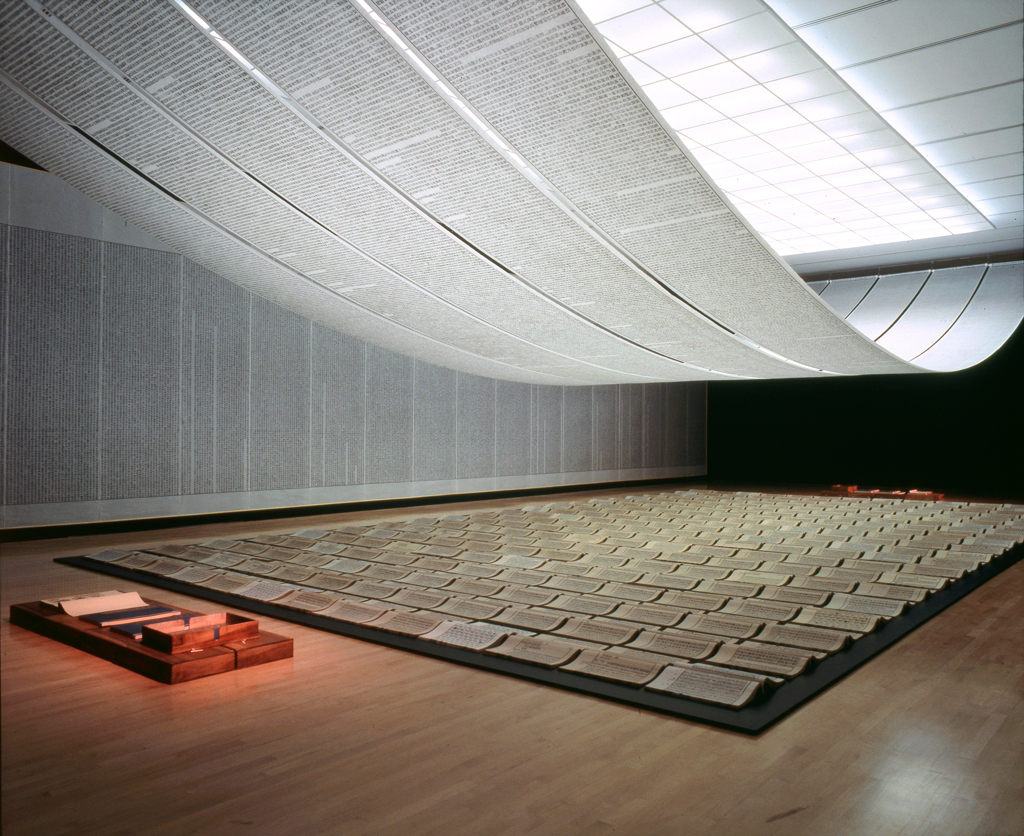

Xu Bing, Book from the Sky, 1987–91, mixed media installation, installation view, National Gallery of Canada, Ottowa, 1998.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Xu Bing has long been considered one of the most important Chinese contemporary artists, but his work has rarely been the subject of career surveys in his home country (he now splits his time between Beijing and New York). On Saturday, a major retrospective of Xu’s work will open at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. On view will be five decades of artwork, including his famed installation Book from the Sky (1987–91), a work that plays on Westerners’ preconceived notions about China through its use of calligraphic text, which at first glance seems to be traditional writing but which actually translates to gibberish. With the retrospective in mind, we’ve gone through our archives and republished excerpts related to Xu’s career, from a studio visit with the artist in 1994 to a report about a controversial Xu work that was removed from a Guggenheim Museum Chinese contemporary art survey last year. —Alex Greenberger

“Bing Xu: 4,000 Characters in Search of a Meaning”

By Jonathan Goodman

September 1994

[Xu Bing] is best known for his stunningly beautiful yet pessimistic 1988 installation Tianshu (the book of the sky). The work comprises three mediums: long, printed banners hung from the ceiling, which are meant to suggest the sutra scrolls that transmit China’s Buddhist teachings; volumes of hardbound books printed from 4,000 esthetically splendid, imaginary characters Xu carved from wood blocks; and wall texts, the traditional means of expressing dissent in China. These three categories cover all means of written expression—but employ senseless terms. The artist spent more than one year just carving the wood blocks. The entire project took three years to complete. As Xu says, “I’m willing to wait years to make a joke.”

In defeating viewers’ expectations that the characters can be read, Tianshu touches on many decidedly contemporary issues: the futility of expression and the inability to communicate in modern times, as well as the deep-seated cultural and political disarray encountered in contemporary China.

“Reviews: Xu Bing at Jack Tilton and New Museum of Contemporary Art”

By Christina Cho

December 1998

Though Xu’s work is not the first to deflate art’s epic seriousness, it seems all the more complicated since the artist himself has become something of a star attraction, a figure circumscribed by labels and hype. Xu is the avant-garde artist struggling under conservative and suspicious authorities or, alternatively, the expatriate artist escaping oppression, then coming to grips with the collision of East and West. Though his work is a testament to how arbitrary labels can be, it has been much called upon lately to represent the art of contemporary China.

There is something unmistakably nostalgic about the fragments of the world Xu has constructed in Giant Panda [1998], and about these charmingly unself-conscious creatures, but the show at [Jack Tilton gallery] lacked the visual complexity of Xu’s Introduction to New English Calligraphy at the New Museum (through January 10, 1999). A more ambitious installation, this also toys with preconceived notions, but goes even further to explore the physical and visual presence of language itself.

Here the gallery space has been converted into a simulated classroom where spectators are invited to practice what initially appears to be Chinese calligraphy. Upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the characters outlined in the primer books Xu has provided are actually careful configurations of roman letters that spell out, among other things, the words to nursery rhymes.

Xu Bing, Square Word Calligraphy Classroom, 1997, mixed media installation. Installation view at Institute of Contemporary Art, London.

COURTESY XU BING STUDIO

“Reviews: Xu Bing at Albion”

By Michael Glover

September 2008

On first encounter, Xu Bing’s game of promising us something, withholding it, then giving us something rather different—and of mixing and matching languages—is both delightful and slightly disturbing. It is as if the words have lost some of their function, leaving us to figure out what they may have gained in the process.

“Puff Piece”

By Lilly Wei

September 2011

For each installment of the series [“Tobacco Project”] . . . Xu Bing created new works based on local circumstances and histories and joined them with previous works. The new art [at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond] will include a 400-pound brick of pressed tobacco emblazoned with the phrase “light as smoke,” as well as a book of poetry composed of tobacco slogans printed on cigarette paper. Among the older pieces in the show are a huge book of whole tobacco leaves printed with an eyewitness account of tobacco cultivation in Jamestown from around 1600, a 40-foot simulated tiger-skin rug made from over half a million cigarettes, and an extraordinarily long lit cigarette laid out on a reproduction of the famous Song Dynasty cityscape Along the River During the Qingming Festival (ca. early 12th century) by Zhang Zeduan. The lengthy cigarette proved problematic during test runs, though. It refused to burn, since cigarette paper is now self-extinguishing.

Neither a health nut nor a smoker, Xu Bing wanted to restore some neutrality to tobacco and examine the plant from an artist’s perspective. “Everyone knows that tobacco is harmful, but we are inseparable from it,” he says. (His father died of lung cancer, a fact poignantly revealed by the inclusion of his diagnostic charts in the show.) But Xu Bing also tells us that farmers and workers revere and depend upon tobacco. And then there is the pleasure. “It is nearly impossible,” he says, “to pass judgment on all of those limitless things that we gain from within its shroud of smoke.”

Xu Bing, Honor and Splendor, 2011, 660,000 1st Class brand cigarettes. Installation view at Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 2011.

COURTESY XU BING STUDIO

“CHINA The Next Generation”

By Barbara Pollack

October 2011

The latest generation, artists born after 1976 and the death of Mao, emerged under a market economy and an open-door policy, accompanied by Western influences. McDonald’s, KFC, cell phones, and DVDs are all taken for granted by these artists, now in their 20s and 30s. Many of them, the products of China’s one-child policy, have attended the country’s competitive art schools and traveled to Europe and the United States as part of their education. They could look to the generation before them and see that success in the international art market was clearly within reach, and many are already making a name for themselves in China and beyond.

“We can see in the work of the younger generation of Chinese artists a uniqueness and creative potential that could be much, much more interesting than the work of the already world-famous artists, in terms of the art market and the work itself,” comments Xu Bing, the MacArthur Award–winning artist who recently returned from the United States to China to become vice chairman of Beijing’s prestigious Central Academy of Fine Arts. “We can see real seeds of contemporary art—a real sense of future,” he adds, “because China is so experimental, the most experimental place in the world.”

“Chinese Contemporary Art Survey at Guggenheim Museum Faces Pushback from Animal Rights Groups”

By Alex Greenberger

September 25, 2017

There’s still a little over a week left before the Guggenheim Museum in New York opens its survey show “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World,” but already the show has been the subject of several statements from activists decrying works in the exhibition for their use of live animals, either in their presentation or production. Two new statements have been released in recent days: one from the American Kennel Club regarding the Peng Yu and Sun Yuan video Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003) and another from Stephen F. Eisenman, an art history professor at Northwestern University, that addresses the ethics of exhibiting that work and two others, by Xu Bing and Huang Yong Ping. Later in the day, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) president Ingrid E. Newkirk also wrote an open letter to Richard Armstrong, the museum’s director, urging him to pull the works from the exhibition.

The statements follow a Change.org petition from last week protesting the Peng and Sun work, Xu Bing’s A Case Study in Transference (1993/94), and Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World (1993), all of which currently incorporate or have incorporated live animals. “Guggenheim – tell the world what you stand for: bold, controversial art that breaks barriers and challenges social norms, which does NOT include the promotion of cruelty against innocent beings,” the petition’s writer, Stephanie Lewis, concludes. At this time of writing, the petition has over 450,000 signatures.

[ad_2]

Source link