[ad_1]

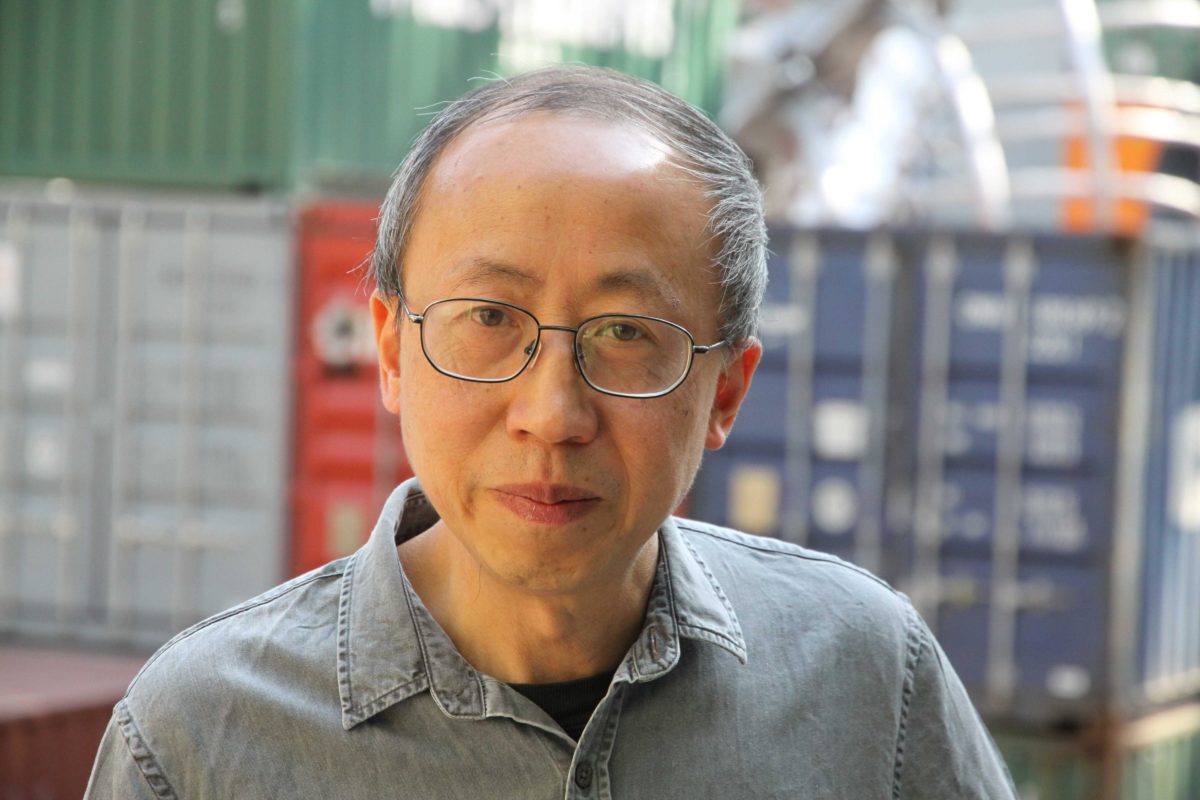

Huang Yong Ping.

GINIES/SIPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

When Huang Yong Ping died in October at age 65, it was a shock for many—one of the most controversial and important artists to emerge from China in the recent decades was suddenly gone. A provocateur whose work incisively explored power structures and globalism with wit and dry humor, Huang was a regular on the international museum scene since an appearance in the legendary “Magiciens de la Terre” exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1989. Based first in Xiamen, China, and then Paris, Huang became an influential figure for many, and one of his works—Theater of the World (1993), an installation featuring live animals that prey on one another in a translucent display case—lent the title to a 2017 Chinese art survey held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York that was curated by Alexandra Munroe, Hou Hanru, and Philip Tinari. Hou and Munroe are among those below who recall Huang’s boundary-pushing art.

Alexandra Munroe

Senior curator, Asian art, Guggenheim Museum, New York

After the rise and fall of civilizations and empires, Susan Sontag wrote, all that endures is art and thought. Huang Yong Ping leaves us with an art that condenses ages of thought, in a form that could only be wrought from the time he lived.

He was, like Duchamp and Beuys who inspired his early Dadaist breakthroughs, a philosopher-artist and radical disruptor. But for Huang, smashing order and meaning was never an end in itself; it was a way to show how order and meaning were limiting inventions in the first place. Ideology, fixed positionality, styles, and political campaigns were figments; the artist is free to imagine his own cosmology.

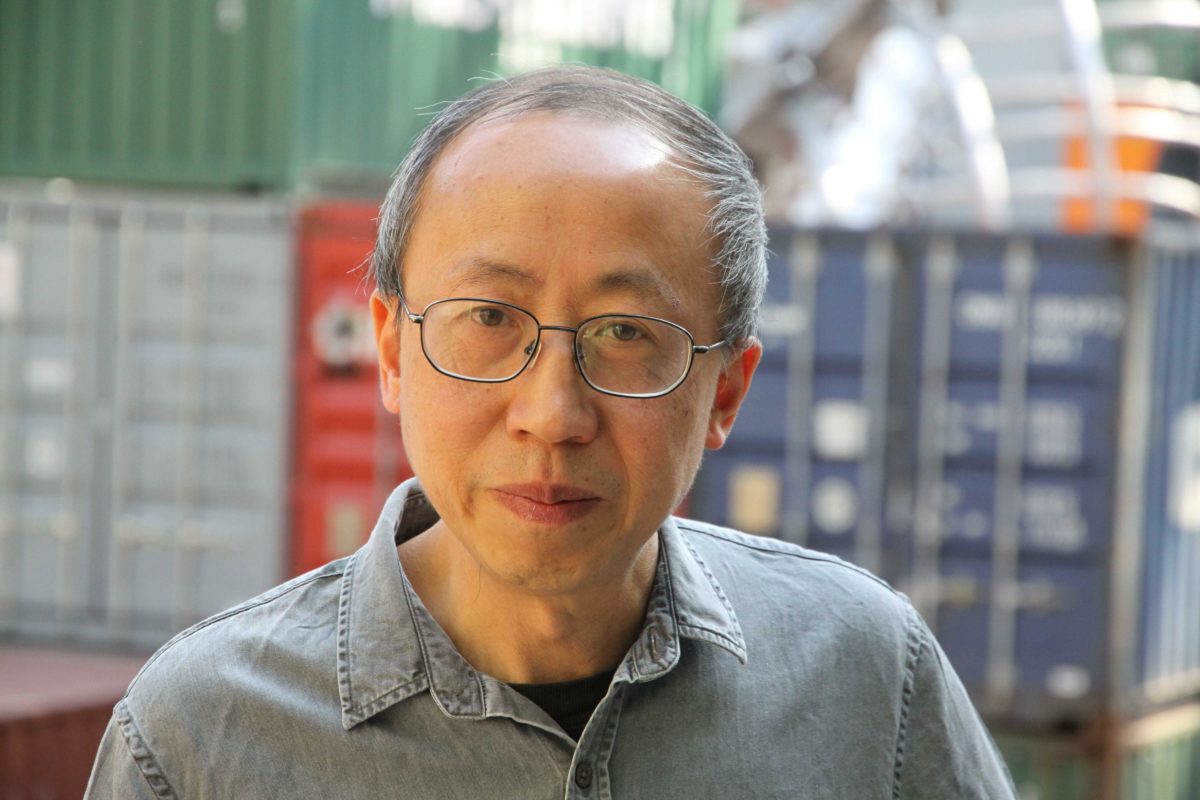

“Theater of the World” was the perfect title for our Guggenheim show, “Art and China after 1989.” We were dealing with a history of gritty, encoded art made by some 70 artists who had survived Maoist China, came of age during the reform era, were whiplashed by Tiananmen, and who then partook of the coincident rise of globalization, China, and world contemporary art. Huang Yong Ping called his 1993 installation, Theater of the World, a “living” work that reflects today’s “globalized context.” It features live turtles, snakes, geckos, beetles, cockroaches, grasshoppers, centipedes, and scorpions in cages that reference Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, Foucault’s modern prison, and a mythological Daoist deity. It was the perfect title because of all it synthesized, and because Yong Ping was the only artist everyone in the show, including the curators, revered, even loved.

An elfin sage, he was witty, nimble, brilliant. He was deeply learned but never pious, catholic in his sources, at ease with the enormity of nature. When the controversy hit 10 days before the Guggenheim show opened, with some 700,000 signatures on a Change.org petition calling for its removal, Yong Ping was bemused. On his flight to New York, he wrote an artist’s statement on an airsick bag (now in the Guggenheim collection) citing Deleuze, Hobbes, and Spinoza, quietly damning the current state of online news and social media that has “engendered a new servility.” He wrote, “The curtain has fallen on the Theater of the World even before it has risen. It has come to an end without even beginning. Is such imperfection not precisely an expression of some other kind of perfection?”

This acrobatics of mental inversion was pure Yong Ping. Art and thought, entwined for the ages.

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World, 1993, wood and metal structure with warming lamps, electric cable, insects (spiders, scorpions, crickets, cockroaches, black beetles, stick insects, centipedes), lizards, toads, and snakes.

©HUANG YONG PING/GUGGENHEIM ABU DHABI

Barbara Gladstone

New York–based dealer

One of the first times I encountered Huang Yong Ping’s work was in 1989, when he participated in the seminal exhibition, “Magiciens de la Terre,” at Centre Pompidou. Throughout his career, he dealt with the political, sociological, and historical issues that shaped a personal trajectory refracted by the course of events on a global stage. His uniquely conceptual art practice fascinated me—he made the wisest critiques through the most intricate and yet engaging gestures. With each show or new body of work, he approached his subjects and installations with a level of intellectual rigor that always surprised and excited me. Since our first exhibition was in 2001, it was a pleasure to see what his imagination would reveal—from a monumental sandcastle deconstructing colonialist histories and instability of capitalism to tower resembling a dragon in flight.

I was fortunate enough to work with him on these and other complex projects during our two decade-long working relationship. His artistic practice forever changed the course of art history on a global scale, and I feel so lucky to have been in his presence. We will miss him dearly.

Works by Huang Yong Ping and Song Dong at the newly rehung Museum of Modern Art in New York.

MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN/ARTNEWS

Xu Bing

Artist

It was only after the Buddha of Bamiyan was destroyed that people realized the importance of art. We were forced to re-contemplate the distance between art and human realities and recognized the significance of such distance. It was only after Yong Ping was gone that the art circle realized a big loss to the art world. People started to know him again only to find out how little we know about him.

Yong Ping and I met at various exhibitions all over the world. But when I try to describe him and his art in more details, I seem to unable to grasp anything, always blocked by his unique kind of smile that cannot be described with existing vocabulary.

Back in 1994, when Yong Ping and Chen Zhen came to New York to prepare their exhibition at the New Museum, they lived in my basement-apartment in East Village which I took over from Ai Weiwei. The fact that the “honor” of having an exhibition in a mainstream museum in New York was first given to our Chinese fellows in Paris made the New York folks a little bit upset. We anticipated to see what they could do. It turned out that Yong Ping transformed the space we were familiar with into an automatic car wash; what was washed clean were in fact the audience. I didn’t know whether he had learned driving by then, but I already learned. For the first time, I was struck by his “undisciplined” art thinking.

In 1998, Zheng Shengtian organized an exhibition for Yong Ping and me at the Art Beatus Gallery in Vancouver. I showed my Square Word Calligraphy Classroom while he presented Terminal. He made a model structured after the Amsterdam airport and put insects and small animals inside—an early version of Theater of the World, which was recently shown at the Guggenheim Museum.

He had strict requirements on the quantity of scorpions, crickets, and small snakes, as he had done careful research on the different species. The next morning, he rushed to the gallery to check on the “arena” like a scientist running to get lab results. I found that he always took things seriously and even looked “cute” at work. There is an anecdote about him among the art circle in Japan: one time, he was preparing an installation titled Emergency Ladder, a ladder of knives; after the work was installed, the night before the opening, the museum owner heard something in the gallery and it turned out that Huang Yong Ping was sharpening the knives by himself!

After the Vancouver exhibition opened, we went to the airport the following day to head to each of our next exhibition venues. I cannot stand spending time waiting at the airport, so I always get to the airport last minute and sometimes miss the flight. While we were discussing when to leave for the airport, I was struck by him again. He insisted following the rules and arriving three hours before the departure time. I said, “no need!” He replied, “I always do this. My foreign languages aren’t good either. What if something went wrong?” This is the most memorable sentence I remembered of his. A skinny Chinese man carrying luggage or materials traveling around the world—the difficulties he must have gone through. That day, maybe he would pass by the Amsterdam airport again, arriving or connecting flights, to go somewhere else for another marvelous project.

Yong Ping lived a simple and low-key life. In life, he was more disciplined and serious than I would imagine. But in art, he was such an unrestrained character, stretching our thinking to both poles. His work and his attitude towards art always push one’s thinking into a corner where there’s no reference or solution. One must somehow adjust their old ways of thinking to enter his work. He is a prophet of times, a magician of thoughts.

Not long ago at the reopened MoMA, Yong Ping’s work and mine were put together again. They were so close that it was impossible to take photos of them separately. It seems to be some sort of destined arrangement, a dialogue, a remembrance of Yong Ping.

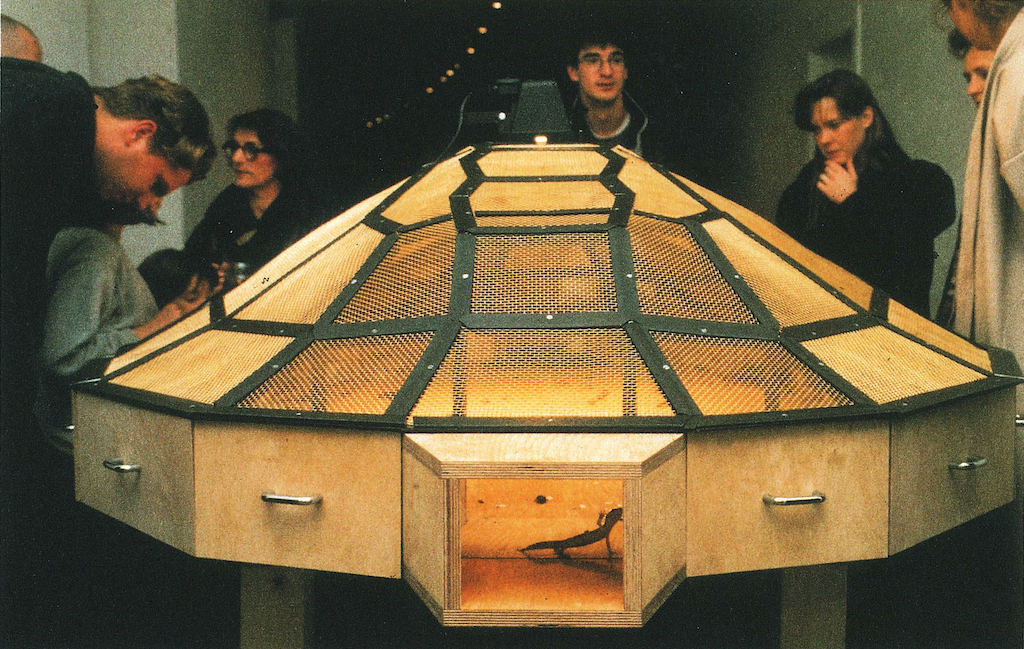

Huang Yong Ping, The History of Chinese Painting and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes, 1987 (reconstructed 1993).

WALKER ART CENTER

Hou Hanru

Artistic director, MAXXI, Rome

We first met in 1988 in China. Of course, he was already known for Xiamen Dada activities, so for me, he was one of the most inspiring artists. He completely changed the notion of art, even in the avant-garde field. At the time, in the ’80s, a lot of avant-garde works were very much dealing with political themes—a lot of critique, resistance, and provocation as art. But his work was very special because he was speaking to philosophical questions, and his approach was inspired by the conceptual way of doing art—really questioning first what art means, and then what subversion means. It’s not simply political subversion in terms of confronting social power, but also how we look at the world in a political way.

He was the most radical artist at the time. He tried to put forward that the idea that there is a paradox between art and anti-art. He was bringing us beyond the normal discussion of the avant-garde. That was very mind-opening. He was maybe the most interesting in terms of writing and philosophical thinking—and he was the most inventive in dealing with the metaphysical reflection on the meaning of art, the meaning of life, the meaning of politics, and so on. For us, at the time, he was a guide.

I wrote something [about Huang] for the catalogue for the “Theater of the World” show—I actually proposed the title for that show, which is from a piece by him. It’s not only that that work is touching on questions of taboo, man, animal, and nature, and what are the limits of power and cultural and social norms. It really proposed a radical way of looking at the world itself. His work is really about continuously unfolding paradoxes and dilemmas—this necessity of changing the way we look at the world.

Thomas Hirschhorn

Artist

Huang Yong Ping is an example to me for his powerful, universal, straightforward, unique work but also for the way he remained strongly focused, hardworking, keeping concentration and staying truthful to art.

Huang Yong Ping, Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank, 2000, installation view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2018.

DAVID REGEN/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GLADSTONE GALLERY

Kamel Mennour

Paris-based dealer

I bought the book of “Magiciens de la Terre,” the iconic show in 1989, at a bookshop—it was priced at what was, at the time, a lot of money. That was at the beginning of the gallery, during the ’90s. My friends and curators told me the artist was living in Paris, and in 2004 or 2005, I had the opportunity to visit. I was thrilled—this was totally the opposite of the kind of art I imagined. In 2006, he joined the gallery.

Working with him was an incredible gift. He would come to an exhibition when he liked an artist, but he was never at dinners and receptions. He was only there to see art, to support a friend he liked. But he was never a socialite. There was only reading and working in his life. That’s it. He would always wear the same trousers—never even buy a new jacket. And he would drink tea.

He was in the French scene, but he could have lived anywhere. That was his choice. Being in the city was important—you know, with Surrealists and Dadaists…. We did Monumenta [an oversized commission at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2008], which was the important project he ever did. It was really difficult. He was small man and a simple man, but he would speak with guts.

[ad_2]

Source link