[ad_1]

Ears figure into art as much as eyes or any other organ, and it’s only been for the better that sound and music-related work has made its way more and more into museums, galleries, and institutions of other kinds in recent years. Whether through performance, recordings, or evocations of different varieties, sound rewards close attention and pays it back with sense memories that are good to store. What follows is a list of some of my favorite sound-related offerings from around the art world in 2019.

Sound Art: Sound as a Medium of Art (MIT Press)

At more than 700 pages and weighing in with heft that could do a number on any foot onto which it might be dropped, Sound Art: Sound as a Medium of Art makes a case for counting as the be-all end-all of books on the subject. Expanding on materials that figured in an exhibition with the same title at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe in Germany, the book surveys many decades of sound-related artwork of disparate kinds. And even the most seasoned sound-art aficionado is bound to find new discoveries in the abundant essays and illustrations between its covers.

Chernobyl, Hildur Guðnadóttir

Somewhere between a concert and an installation, the first live “performance” of music from the HBO TV series Chernobyl counted among the best presentations of sound-related work I’ve ever seen. Commissioned by the Unsound Festival in Krakow, Poland, it was set in an empty factory building on the outskirts of the city, where composer Hildur Guðnadóttir (who also swelled to attention this year for her soundtrack to the movie Joker) was joined by three others to summon the surreal field-recordings and creaking classical music that she effectively cast as extra characters on the show. The aural aspect was bathed in amorphous lighting that added to the otherworldliness, and the dynamic range between contemplative quietude and cataclysmic blasts was something to behold. Its site-specific setting will be hard to replicate, but plans are in the works to present the project elsewhere around the world.

Helena Majewska

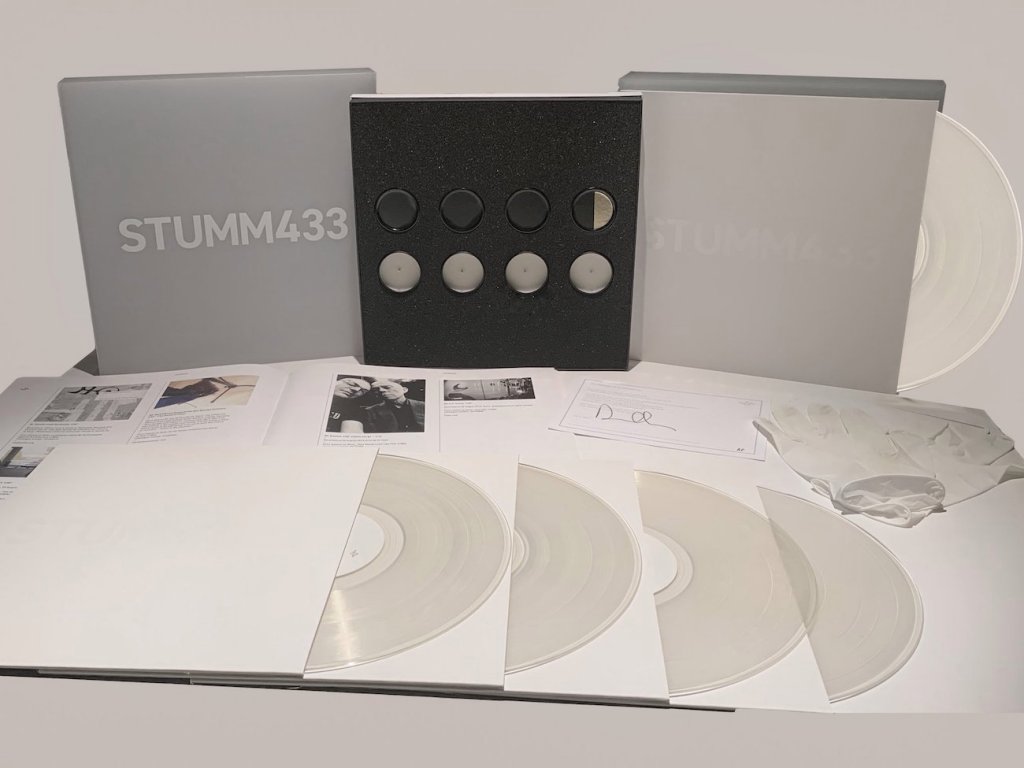

Various artists, STUMM433 (Mute)

Assembled for the 40th anniversary of the storied record label Mute, this very elaborate set (pictured at top) includes five vinyl LPs, a set of scented candles, and even a pair of white gloves to doff when communing with materials encased in a frosted plastic box—all in tribute to composer John Cage’s seminal 1952 “silent” composition 4’33”. Cover versions of the piece were recorded by the likes of New Order, Einstürzende Neubauten, and Depeche Mode, and graphic designers were invited to make visual interpretations of the work. Of his contribution, Australian-Icelandic composer Ben Frost writes in the liner notes: “I made several attempts at the piece but this one was the best. In the final movement the LA lifeguard turned up on the horizon with their rescue boat.”

Eliane Radigue, Occam Ocean

In concert in the performance space at the new Pace Gallery flagship in New York, Eliane Radigue’s Occam Ocean brought to a revving and ridiculous city a stillness that would be hard to overstate. Though the 87-year-old composer is best known for decades-old electronic works that follow long synthesizer tones to a sort of vanishing point, the more recent compositions enlisted here—in a program organized by the roaming curatorial enterprise Blank Forms—apply similar methods to sounds from cello, harp, tuba, and bassoon. Sometimes they played solo; other times they came together in subtle assembly. At all times, the music made for an immersive minimalist atmosphere in which sound and all that surrounds it became one.

Hyla Skopitz/Courtesy Pace Gallery

Kevin Beasley’s “Assembly” at the Kitchen

Over three weekends of programming at storied New York performance space the Kitchen, Kevin Beasley fleshed out aspects of his own artistry (as a sculptor as well as a summoner of sound) with a lineup of colleagues and friends who covered vast stylistic terrain. Techno communed with noise, meditative modular synthesis melded with visceral vocalizations, and—on the weekend I went—an antagonistic set by Wetware got the attention of Genesis Breyer P-Orridge before the evening ended with an intensely powerful solo piano performance by Jason Moran.

Joshua Abrams & Natural Information Society, Mandatory Reality (Eremite Records)

This album of entrancing jazz follows patterns that start out seeming simple and—without changing much at all—grow more and more complex with time. The lineup of the expansive band fans out into different groupings prominent on the jazz and improv scene, and Lisa Alvarado—credited on this album for playing gongs, harmonium, and flute—lent appropriate album art of the kind she shows as an artist on the roster of Bridget Donahue gallery in New York.

Tony Conrad, Writings (Primary Information)

One of many essential books published this year by Primary Information, a long-in-the-making compendium of writings by polyglot artist Tony Conrad gathered thoughts by a singular character who got his start in the 1960s and kept chugging until his death three years ago. Some of it applies to his work as an experimental filmmaker (see The Flicker and many other abstract works for the screen) and a Fluxus-affiliated artist of various kinds. But a good deal deals with the kind of droning, drifting music he made an integral part of the avant-garde lexicon. In one essay, he shouts down the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras for having locked Western music into too tight a cage. In another, he broods over “corrupt terms” and “frozen clichés” that hamper radical art and inhibit the kind of interdisciplinary looseness and goofiness that Conrad made his forte.

Ben Vida, Reducing the Tempo to Zero (Shelter Press)

This four-hour drone composition by musician/artist Ben Vida goes everywhere and nowhere at once. The electronic tones created through digital and analog synthesis stretch and smear in ways that can make those of a certain disposition serene, and it all works—as a project description states—as “a temporal nesting doll—a meditation, conceived by Vida as a part of a daily practice which embarked upon sustained periods of focused creation and listening.”

Last Night, Martin Beck (White Columns)

Reissued this year by White Columns in a “revised second edition,” Martin Beck’s beautifully simple artist book Last Night tells a story by way of nothing but a list of records played by David Mancuso (the proto-DJ who invented disco, by many measures) at the final Loft party at 99 Prince Street in SoHo in 1984. The Loft continues on at a different location and with mythology still in store (even after Mancuso died in 2016), and engaging with Beck’s book makes for a special kind of experience—with the slow flipping of pages evoking a long night out on the dance floor.

Catherine Christer Hennix, Poësy Matters and Other Matters (Blank Forms)

This two-volume set of writings navigates vast parts of an even vaster world charted by the mind-bending musician, mathematician, and artist-of-many-kinds Catherine Christer Hennix. Her music figures in the lineage of Minimalism and ritual practice of a kind followed by colleagues such as La Monte Young and Pandit Pran Nath, and her endeavors in other realms including math (with which she worked at MIT in the ’70s) and psychoanalysis are no less notable. The whole of it would be impossible to circumscribe, but I like what’s signaled in a bit that Hennix wrote in reference to a dismissal of a musical piece of hers inspired by the “intuitionist” mathematician L. E. J. Brouwer, as observed by avant-garde peer Henry Flynt. “Henry insisted that this type of music,” the author writes, “could only be sustained by a ‘Higher Civilization.’”

Fred Moten, All That Beauty (Letter Machine Editions)

In his newest poetry book, Fred Moten included a piece he wrote for the catalogue for Zoe Leonard’s “Survey” show at MOCA Los Angeles and the Whitney Museum, and a bit about seriality and sound in relation to Leonard’s displays of thousands of postcards of Niagara Falls really got me. Moten writes, about hearing images of the sort, “We get so worried by the gap between what we want from the photograph and what we want from photography that we start to wonder if this phonography, hidden in plain sight’s plainsong, is mere ambience.” He goes on, in tribute to hopes for recognition of “an aural, auratic background,” a bit later: “We want to want a troubled, textured, nasty, nastic, gnostic background; a grooving, mangrovic background with an eccentric edge; a sequential hum that breaks because it’s broken, so we can see what the photograph does to the hum as line or plane and hear how it sounds through the sound so we can see how to sense more fully the flavorful, funky reverberations that emerge from the contrapuntal interplay of multi- and anti-linear audio in the blur and grind.”

[ad_2]

Source link