[ad_1]

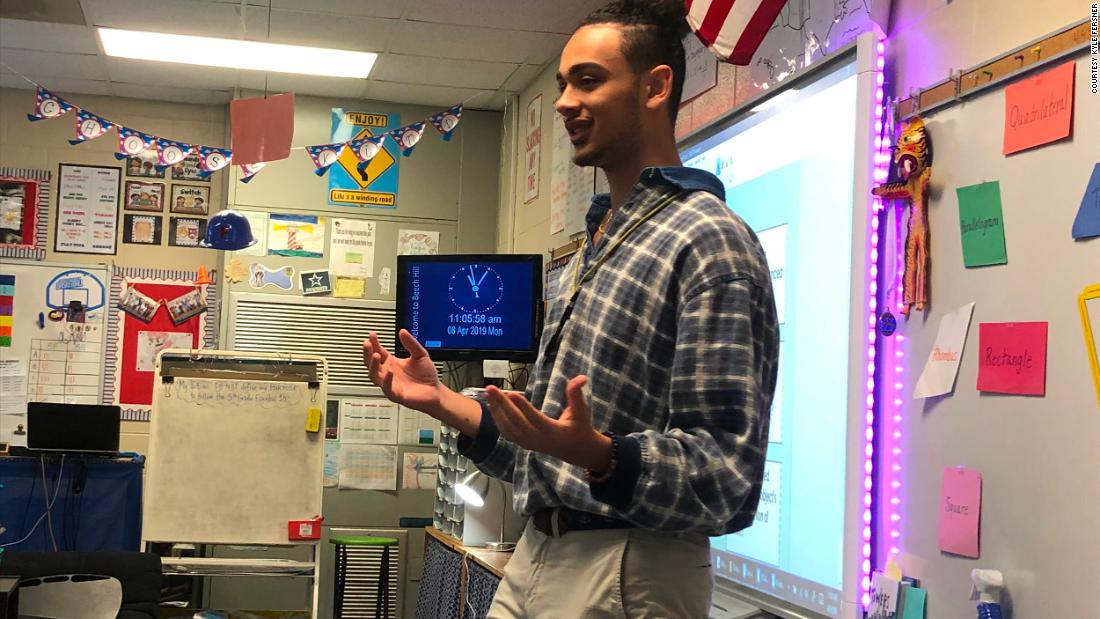

Fersner was observing the boy’s class as part of his school’s teacher cadet program in South Carolina that he’d joined out of curiosity.

“Hey, you look like a rapper,” Fersner recalled the boy saying.

“He said I look like Lil Pump,” a popular rapper of Hispanic descent. At the time, Fersner’s hair was long and braided, like Lil Pump’s.

“In that instant, I knew this is something I can make a difference with,” he said. “More than likely he’s never had a teacher who looked like me.”

Minority male teachers are hard to come by

Black men make up 2% of teachers in the US, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Research shows that for minority children, having at least one teacher that looks likes them is a key to their success, said Roy Jones, a professor at Clemson University’s College of Education.

“It’s not only important that the teacher looks like and reflects the demographic of the student they’re teaching. It’s because of the experience and background. Their ability to relate and identify with the child is critical.”

“Call me MISTER” recruits teachers of color

Since the program began in 2000, it has expanded to colleges in 10 more states.

“Our ‘Misters’ come from the same environment, the same places and spaces that the children come from. That’s why they relate so well and can bring them along,” Jones said. The students also live together as a sort of brotherhood, to encourage each other on the path.

Jones cites other, higher-paying professions as a major reason young black men don’t become teachers.

“You’ve got black males going to college that aside form athletics are choosing to go into health professions, business, engineering, social science.”

When it comes to college athletics, Jones says, there’s a much stronger pipeline of recruitment and support.

“Not only money, but they get the tutoring, the counseling, their own separate dormitory, they eat well — because of what their perceived value is.”

And while many minority students know about the resounding success of athletes from their neighborhoods, “You’ll never be able to touch or shake hands with Lebron James or Dak Prescott, but you can sure touch the hem of a “Mister” in your classroom,” Jones said.

“The guys are so dynamic — that’s what changes the narrative and the perception of going into teaching as a vocation.”

Over the past 19 years, 275 men graduated from the program and received job offers. Jones said 95% are still working in the classroom as teachers and the other 5% are principals or working in education leadership roles in South Carolina.

Changing perceptions of a teacher

Fersner is now officially a Call me Mister man. The freshman joined the program at College of Charleston. He plans to double major in elementary education and psychology.

He admits salary was one of the reasons he didn’t want to go into teaching initially.

“But there came a point — you can sit back and let issues go on or you can be part of the solution. I can be part of the reform that brings higher wages to teachers,” he said. “Once I realized, that’s when I shifted.”

He thinks back on the little boy who changed his mind — and the lesson he learned that day.

“Your image doesn’t say who you are. You say who you are through your image.”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Kyle Fersner’s school. He attends College of Charleston.

[ad_2]

Source link