[ad_1]

In the 1970s, Carlos Alfonzo belonged to an underground community of young artists in Havana who pushed back against the Sovietization of Cuban culture by embracing new forms of expression that drew on Afro-Cuban religious imagery, premodern sign systems, and vernacular craft. This group—which included Juan Francisco Elso, José Bedia, and Ricardo Brey—gained recognition in exhibitions like the landmark “Volumen Uno” (1981) and the Havana Biennial (founded in 1984). By then, however, Alfonzo had departed from their ranks: he left the island in the 1980 Mariel boatlift, settling in Miami Beach and becoming an artist of exile rather than a member of the “1980s generation,” as the group was later known. In the United States, he developed a distinctive pictorial language and complex style.

“Carlos Alfonzo: Witnessing Perpetuity,” at LnS Gallery in Miami, gathered major works from every phase of the artist’s career, which was cut short by his death from AIDS-related complications in 1991, at age forty-one. The impressive exhibition began with rarely seen late-1970s works characterized by a schematic, quasi-primitivist figuration. Three ink drawings titled “Tribal Series” (1979) display abstract petroglyphic forms floating in vertical columns on white grounds. Another drawing from this period, Yo nunca te tuve bajo un árbol (I Never Had You Under a Tree, 1976), features simplified graphics of palm trees, moons, fish, and human figures packed tightly together to form a dense allover pattern.

Soon after immigrating to the US, Alfonzo began pursuing a more expressionistic approach and took up motifs that would recur throughout his mature work—such as tongues pierced with nails, eyes and smiling mouths elongated to look like tropical fruits, and spirals suggesting coiled phalluses. It took time, however, for him to find the optimal way to bring them together compositionally. Characterized by slashing, frenzied brushstrokes, his paintings from the early ’80s possess a new high-voltage energy, but the results are often muddy and confused. In Petty Joy (1984), repeating motifs are piled incoherently atop one another across an unstretched canvas tarp, the composition flattened by an excessive use of white.

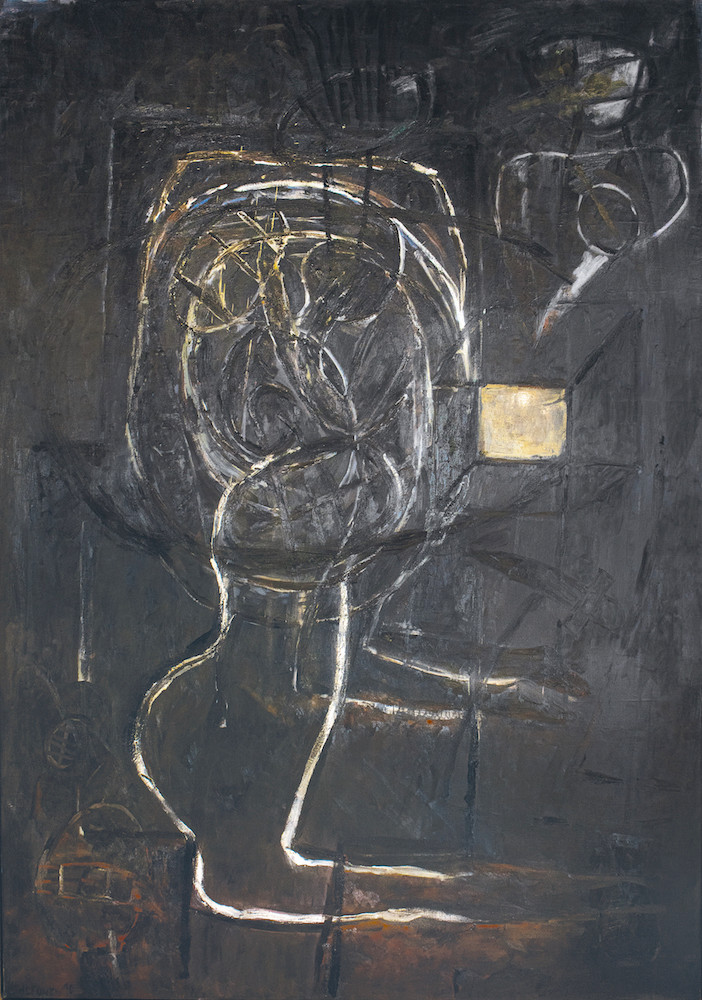

In the second half of the 1980s, things appear to have clicked for Alfonzo. The large vertical painting Shift (1987) feels at once brooding and full of energy, with areas of dark earth tones and blacks punctuated by furiously applied pink, yellow, white, and green passages. The composition is organized around a large spiral surrounded by motifs including knife-like shapes, eyes, and teardrops. Employing imagery linked to Afro-Caribbean religious practices, the painting suggests an abstracted altar erected deep in the woods, covered in offerings.

The Loumiet Collection, courtesy LnS Gallery

During the final years of his life, while his health was deteriorating, Alfonzo produced the best works of his career: the stately, melancholic “Black Paintings” (1989–1991), two of which were included in the show. The paintings unveil themselves slowly: at first, the ten-foot-tall Home (1990) seems to depict only the white outline of an abstracted figure on a black ground that nearly overwhelms it. But the painting is brimming with partially hidden details, such as symbols roughly painted in subtly modulated shades of black. The work has a quasi-religious feel: its pictorial space is as tightly compressed as that of a medieval icon painting or an early illuminated manuscript, while its formal severity and architectural scale place it in the realm of altar backdrops or mausoleum doors. Made during the height of the AIDS crisis, the “Black Paintings” are not contemplative or peaceful. Instead, they express both an intense rage and a hope that flints in the dark, each element feeding on the other.

[ad_2]

Source link