[ad_1]

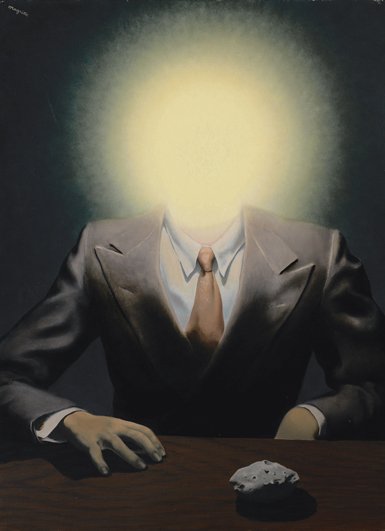

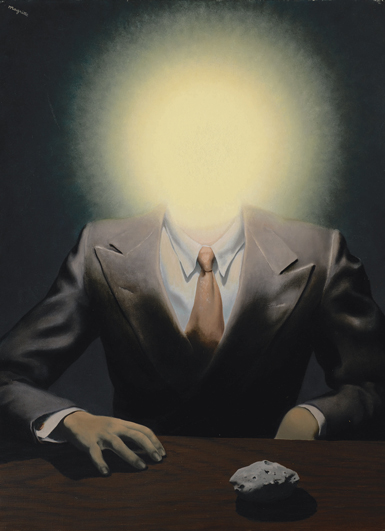

René Magritte, Le Principe Du Plaisir, 1937, sold for $26.8 million, a record for the artist. It was the top lot of the evening.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Studded with a gripping array of top-class material that seemed to echo the collective angst of today’s headlines, Sotheby’s Impressionist and modern evening sale on Monday finished with a rock-solid $315.4 million result, though 16 of the 65 lots offered failed to sell, for a somewhat flabby buy-in rate by lot of 24.6 percent. The tally, including fees, fell comfortably midway between presale expectations of $283.9 million to $393.4 million. (Estimates do not include buyer’s premium.)

That total easily hurdled last November’s $269.7 million result on 59 lots by 17 percent. Sotheby’s arranged 23 third-party guarantees, known here as “irrevocable bids,” whose backers can receive a financing fee for their trouble, and extended a single house guarantee. The firm’s solo risk, on a star lot that failed to sell, assuredly wiped out what should have been a profitable evening.

In all, 41 of the 49 lots sold for $1 million dollars, and of those, an impressive seven exceeded $20 million dollars. Five artist records were set.

(All prices reported include the hammer price plus a buyer’s premium, calculated at 25 percent of the hammer up to and including $300,000, 20 percent of any amount in excess of that up to and including $4 million, and 12.9 percent for anything beyond that.)

The evening started with Max Pechstein’s dapper, full-length Portrait of a Man: Bruno Schneidereit (circa 1912), showing the Berlin-based architect and Pechstein patron with a cigar, top hat, and fur collar, which sold for $735,000 (est. $600,000–$800,000).

Wassily Kandinsky, Le Rond rouge, 1939., sold for $20.6 million.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

It was followed by a color-charged Heinrich Campendonk expressionist abstraction, Der Traum (The Dream), 1914, which made $1.58 million. (est. $1.2 million–$1.8 million). It was part of a dozen-lot trove from a European collection evocatively branded by Sotheby’s as “The Triumph of Color.”

Wassily Kandinsky’s radical and graphically rich abstraction Le Rond Rouge (1939) was part of that pack, and sold to a telephone bidder for $20.6 million (est. $18 million–$25 million). It was backed by an irrevocable bid, as was an earlier, Blaue Reiter-era Kandinsky painting, Improvisation on Mahogany (1910), which sold to another telephone for $24.2 million (est. $15 million–$20 million), sparking a round of appreciative applause in the York Avenue salesroom.

A third Kandinsky in the group, Zum Thema Jungstes Gericht (on the Theme of the Last Judgment), 1913, bristling with the exciting energy of avant-garde abstraction, sold to an anonymous telephone bidder for $22.9 million (est. $22 million–$35 million).

Another top-class entry, Maurice de Vlaminck’s jaunty, Fauve period composition Paysage au bois mort (Ramasseur de bois mort), 1906, sold to New York private dealer Nancy Whyte for $16.7 million (est. $12 million–$18 million). Hugo Nathan of London’s Beaumont Nathan was the underbidder. It last sold at Christie’s London back in March 1984 for the equivalent of $496,400.

The “Triumph of Color” group collectively made $111 million compared to presale expectations (before fees) of $88.4 million to $129.5 million.

Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation Auf Mahagoni (Improvisation on Mahogany), 1910, sold for $24.2 million.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

A second themed grouping of works from an American collection with proceeds going to a charitable institution—similarly branded as “Painted Light”—also benefitted from some outside backing.

It was led by Camille Pissarro’s Prairie avec vaches, brume, soleil couchant a Eragny (1891), capturing the light of the river Epte in Eragney, France, and made $3.74 million (est. $2 million–$3 million). It was the painting’s fifth appearance at auction since 1989, according to the catalogue entry. It last sold at Christie’s New York in November 1998 for $772,500.

Beyond those themed offerings, a dark and somewhat gloomy townscape of Krumau by Austrian master Egon Schiele, City in Twilight (The Small City II), 1913, which the artist often referred to as “Dead City,” attracted a deep-pocketed posse of five bidders and sold to the telephone for $24.6 million (est. $12 million–$18 million). It sold without the benefit of any type of guarantee, so one might surmise this was a market-correct price for a painting in somewhat distressed condition—though one with an enhanced status, as a recently restituted work (it was looted by the Nazis from the Vienna-based Elsa Koditschek).

A second Schiele, perhaps more familiar in terms of subject matter, Seated Female Nude with Tilted Head and Raised Arms (1910), a gouache, watercolor, and black crayon on paper, sold to another telephone for $1.52 million (est. $1 million–$1.5 million). It came backed with an irrevocable bid.

At one point in the bidding tumult, a woman seated in the salesroom made a single bid at over $1 million and auctioneer Harry Dalmeny, aka Lord Dalmeny, the chairman of Sotheby’s U.K., said dismissively, “Oh, a one-note wonder.” (I usually don’t comment on auctioneering etiquette, but Dalmeny’s performance from the rostrum at his first-ever New York evening sale was riddled with snide comments, more in tune with charity sales.)

Oskar Kokoschka, Joseph de Montesquiou-Fezensac, 1910, sold for $20.4 million.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Back to the real drama: an important, restituted painting from the legendary collection and inventory of German avant-garde dealer and publisher Alfred Flechtheim, Oskar Kokoschka’s portrait of a suave yet decaying Joseph de Montesquiou-Fezensac (1910), sold to Andrew Fabricant of Gagosian for a record-shattering $20.4 million (est. $15 million–$20 million). Nick Maclean of Eykyn Maclean was the underbidder, with his anonymous client gamely directing the bidding action at his side.

A young Kokoschka painted portraits of sickly friends of his patron, architect Adolf Loos, who was visiting his girlfriend at a posh Swiss sanatorium in the Alps, and Montesquiou-Fezensac was among the sallow-faced crowd. Kokoschka, of course, was later branded a degenerate artist by the Nazis, and hundreds of his paintings were confiscated. Flechtheim’s heirs recovered the painting from the Moderna Museet in Stockholm earlier this year.

Another Flechtheim masterpiece, though one unsuitable for timid viewers—Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Das Soldatenbad (Artillerymen), 1915, which depicts about 20 dead-faced nude men crowded together in a shower room—sold to a telephone bidder for $22 million (est. $15 million–$20 million). Informed by the artist’s time in World War I, it was also restituted to the Flechtheim heirs in 2018 after a circuitous and complex postwar journey through several American museums, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Both the Kokoschka and the Kirchner were backed by irrevocable bids.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Das Soldatenbad (Artillerymen), 1915, sold for $22 million.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

The evening at Sotheby’s York Avenue headquarters started to feel apocalyptic in nature, with a carousel of strong images topped in intensity by Ludwig Meidner’s extraordinary and still-scary Apocalyptic Landscape (1912), whose fractured, fire-filled city suggests a 9/11-like nightmare. It sold to New York and London dealership Lévy Gorvy for an artist-record $14.1 million (est. $12 million–$18 million), and was backed by a brave-hearted irrevocable bid. (Not sure who would want this screaming masterpiece on a living room wall.) It last sold at Sotheby’s London in October 2001 for the equivalent of $1.13 million.

A first-time evening entrant to an Impressionist-modern sale, indicative of the changing winds (or strategies) of art-historical categories, American Marsden Hartley was represented by an emblematic abstraction, Pre-War Pageant (1913), carrying an unpublished estimate in the region of $30 million, turned out to be a bomb, and was bought-in.

Sotheby’s guaranteed it, and will now have to live with a “burnt” painting, keeping that big number on its books until it finds a buyer. The richly colored composition of a regimental flag riffs in part on Hartley’s love affair with a Prussian officer in Berlin, as well as the pomp and circumstance, and romantic masculinity, of military insignia.

Back in the more familiar terrain of blue-chip contenders, Joan Miró’s rich pastel on paper Figure (1934), realized $7.3 million (est. $7 million–$10 million), and Henri Matisse’s reclining Nue au peignoir (1941) sold for $4.22 million (est. $4 million–$6 million).

And René Magritte provided a needed palate enhancer to the Sturm und Drang of the German and Austrian Expressionists, with the amazing Le Principe de plaisir (1937), a commissioned portrait of the storied English aesthete Edward James. As requested by the artist, James provided a photograph—one taken by Man Ray, no less—of himself posing in a suit and tie at a table. Magritte rendered the image with great precision, apart from the sitter’s head, which he transformed into a glowing aura of light. It realized a record $26.8 million (est. $15 million–$20 million). The top lot of the sale, it came to market “naked”—that is, without a financial guarantee.

“The top valued lots this evening were rare and important,” said Nathan, who underbid a Fauve Vlaminck and bought the Jean Arp, Torse (1931, cast 1958–60), for $2.3 million, “whereas it was different from the top lots last night at Christie’s. Things that deserved to do well and [were] of museum quality were rewarded, and there was depth in the bidding.”

The evening action resumes at Christie’s on Tuesday with a single-owner sale from the collection of Barney Ebsworth.

[ad_2]

Source link