[ad_1]

A nation divided against itself and a monarchy beset by scandal. A Tory prime minister by turns humorous and harsh, statesmanlike and petty. A left opposition defeated and hungry for fresh leadership. A cohort of celebrity painters and sculptors in thrall to the 1 percent. And a legion of other artists scraping out livings by any means necessary: commercial work, teaching, modeling, serving food.

The parallels between William Blake’s Britain of the 1790s and the Brexit-era United Kingdom go even further. There emerged among the working classes in the late eighteenth century what the historian E.P. Thompson called “the chiliasm of despair”: a fear, rooted in Christian eschatology and working-class Methodism, that the coming end of the century meant the end of the world.¹ The attitude was bound up with anger over increasing economic inequality, concern about the king’s competence, and alarm over the French Revolution (and, subsequently, the execution of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette).² Urban workers and small tradesmen, anxious about losing what little wealth and status they had, generally preferred the devil they knew (the English king) to the one they didn’t (revolutionary ideas from France). And rural workers, paralyzed by fear of impoverishment and a descent into the degrading system of poor relief, were similarly dispirited. It was a socioeconomic environment of “rich land and poor laborers,” to borrow radical journalist William Cobbett’s characterization of England in the 1820s.³ Here is where Blake’s Britain most closely resembles the UK today, and the United States, too.

Millions of people in both countries are afflicted with what British doctors have informally named “shit-life syndrome” (SLS). Symptoms include clinical depression, drug abuse, diabetes, morbid obesity, and increased death rates for people in midlife.4 SLS sufferers in the north of England (formerly Labor Party voters) and the US Midwest (formerly Democratic Party voters) helped put in power Boris Johnson and Donald Trump, the very avatars of neoliberal policies that have hurt them, such as austerity in the British case and tax cuts for the rich in the American one. What kind of art can awaken working people from the self-destructive sleep of despair? What sort of vision can arouse their desire for democratic change, and even revolution?

Yale Center for British Art.

Those were questions that Blake (1757–1827) asked from the beginning of his career to the end, and to which his complex, composite art—poetry, painting, engraving, and printing—provided answers. They should have been the basis of the Blake retrospective held recently at Tate Britain. Instead, Tate curators Martin Myrone and Amy Concannon offered what I would call a liberal Blake—someone neither radical nor conservative, neither mad nor sober, and neither bourgeois nor bohemian. A few wall labels gestured toward his radicalism, but the show never demonstrated it by juxtaposing his and his contemporaries’ works or even by elucidating key works by him with thoughtful didactics. In place of a compelling thesis, the Tate exhibition offered a veritable catalogue raisonné (more than three hundred works), the weight of which served to obscure the complexities of the art and nearly to erase what W.J.T. Mitchell called “the dangerous Blake.”5 At Tate, Blake functioned as an art brand, of the familiar, modern kind.

This was not the Blake I came to know while organizing “William Blake and the Age of Aquarius,” an exhibition, held at Northwestern University’s Block Museum of Art in 2017–18, that was concerned with the artist’s impact on the New York and West Coast avant-gardes of the 1950s and ’60s. Blake was a consistent political and artistic radical who offered a vision of a transformed future.

A brief synopsis of his activism and art will be instructive here. In 1780, Blake was among the crowd that stormed Newgate Prison and freed its inmates. (The assault was the culmination of the Gordon Riots, a set of events that started as an anti-Catholic protest and turned into a fundamental challenge to inequality, the king, and an unrepresentative parliament.) In 1791, he wrote a long poem about the French Revolution. It was too admiring for even his left-wing publisher, John Johnson, to present to the public. Two years later, he wrote and illustrated a book, America a Prophecy, that celebrated the American Revolution and endorsed abolitionism. In another book he published that year, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, he examined, through metaphor and personification, what is today called “rape culture” and argued for women’s sexual and creative emancipation. In 1804, Blake was charged with sedition for punching a soldier and allegedly saying, “Damn the king.”6 (It’s unclear if he actually uttered the phrase, though he wrote, in private literary notations, “Every Body hates a King.”7) Luckily, he found a good lawyer and got off. After that close call, he largely kept a low profile.

Blake’s preferred vehicle for his radical messages was illuminated books—a medium, resurrected from the Middle Ages, that he transformed through a printing technology he invented: relief etching. The technique allowed him to combine image and text in a single compositional process, thereby overcoming the divisions of labor between author, typographer, illustrator, engraver, binder, and publisher that frequently—since profits had to be split—left all of them broke. Blake first deployed the process in 1788, for his book All Religions Are One.

The Fitzwilliam Museum.

To produce a relief etching, he would render his imagery and words on a metal plate using a varnish resistant to corrosive acids. He would then apply acid that would bite the exposed areas of the plate to a shallow depth, after which he would pour off the acid and scrape off the varnish. His composition and writing would appear on the plate in relief, as on a woodblock in woodcut printing. After carefully inking the raised portions with a dauber and applying the sheet of paper, he would put the plate through an etching press—gently, so that there was only slight embossing on the verso of the paper, allowing both sides to be used. He could make almost innumerable copies from the metal plates, but in practice, the lack of demand for his books limited his editions to less than fifty. There remains some controversy about other details of Blake’s technique—especially concerning the coloring of sheets—but that’s the gist of it.

Blake did not develop his illuminated printing only as a means of maximizing returns. In fact, his method proved extremely labor-intensive, and he earned his modest living mostly as a conventional engraver, the trade for which he had been trained as a youth. Relief etching, though, allowed him to think, experiment,

and be creative across all stages of production. Every letter or mark on the plate, every use of the dauber, and every meticulous wiping away of ink could be a spiritual art-making activity. He could respond quickly to bursts of inspiration, making additions, changes, and corrections without laboriously resetting type and burnishing or hammering out unwanted designs. In the end, however, Blake’s invention was sui generis—no other prominent artist used it, and its precise technology remained generally unknown for about 150 years after his death.8

TO BLAKE, THE ESSENCE OF FREEDOM was imagination, which he believed everyone possessed from birth. In the early 1790s, he self-published The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, a series of illuminated texts—some prose and some poetry—that inverted the prescriptive message of the Book of Proverbs from the Hebrew bible. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell was, among other things, a treatise on imagination and a critique of what is today called ideology: the intellectual blinders that prevent people (especially working people) from correctly seeing the nature and cause of the oppression they suffer. Blake writes: “For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.”9 A section called “Proverbs of Hell” offers explicit challenges to biblical teaching as well as religious and secular law. Here are some of them:

“The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.”

“He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence.”

“The most sublime act is to set another before you.”

“Prisons are built with stones of Law, Brothels with

bricks of Religion.”

“The fox condemns the trap, not himself.”

“The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses

of instruction.”

“The soul of sweet delight, can never be defil’d.”

“Damn, braces: Bless relaxes.”

“Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse

unacted desires.”10

The meanings of Blake’s proverbs are uncertain. Does all excess lead to wisdom? Can infanticide ever be OK? Why is damning better than blessing? But even with their ambiguity, the proverbs are almost as startling today as they were more than two centuries ago. It’s unsurprising that Blake has been celebrated by such unconventional figures in art and literature as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Walt Whitman, Francis Bacon, Diane Arbus, William Burroughs, Jay DeFeo, Allen Ginsberg, and Jimi Hendrix, to name a few.11

Tate, London.

Perhaps nowhere is Blake’s imagination in greater evidence than in the elaborate mythology he devised for his work. His “prophetic books”—as the twelve illuminated books in which he employed this mythology are known—are set in a weird time period that seems at once ancient and future, and feature bizarrely named characters such as Thel, a shepherdess who can be found talking to a lily, a cloud, a worm, and a clod of earth; Albion, who represents humanity and the liberated English people; Orc, who is energy personified and the spirit of revolution; Los, a creator, an artist, and sometimes Blake’s alter ego; Urizen, who symbolizes repressive reason or conscience; and Ololon, an “Emanation” from John Milton. (In Blake’s myths, Emanations were the female counterparts of the essentially mixed-gender male heroes.) There are many more such figures in Blake’s mythology, and to make matters more confusing, they sometimes change identities from one book to the next. (A thick dictionary of Blakean characters, plots, locations, and references was published about fifty years ago.12 This book is itself so complicated that it could use a dictionary.)

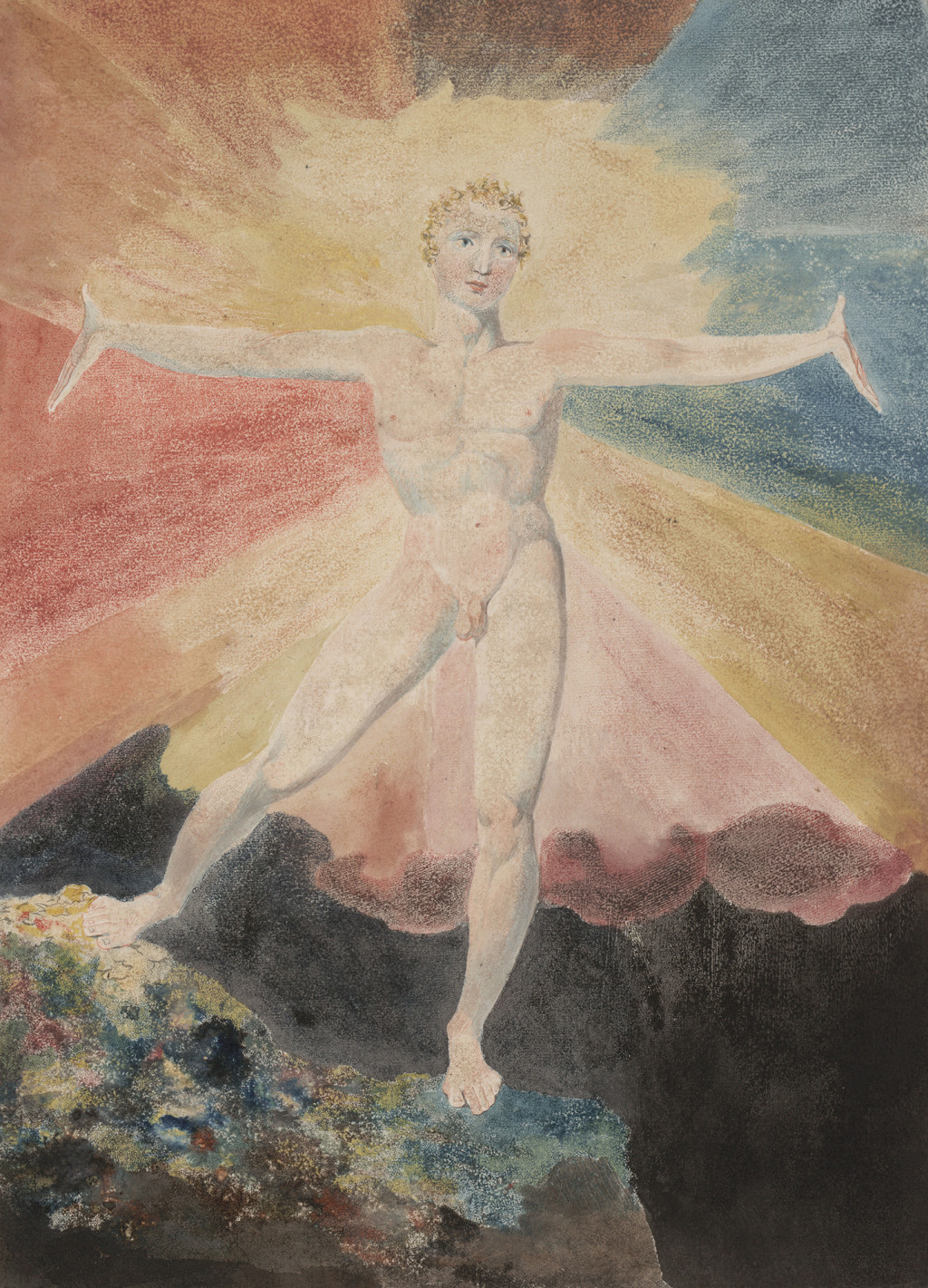

A nude Albion greeted visitors to the Tate exhibition, in the print Albion Rose (ca. 1793). Surrounded by a rainbow-colored starburst, he stands at the center of the composition, at once dancer and Vitruvian Man, freed slave and revolutionary. Blake intended the figure’s erotic energy to inspire the young people of Britain to smash the oppressive state. The text below an uncolored version of the print, not included in the show, reads: “Albion rose from where he laboured at the Mill with Slaves / Giving himself for the Nations he danc’d the dance of Eternal Death.” The lines anticipate some found beneath another, more frankly sexed nude that Blake depicted in America a Prophecy:

Let the slave grinding at the mill, run out into

the field:

Let him look up into the heavens & laugh in the

bright air;

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For Empire is no more, and now the Lion & Wolf

shall cease.

Though Blake was not an economist or a political theorist, he understood that the emerging society of industrial capitalism was limiting people’s access

to imagination and vision. In 1799, he wrote a letter to Reverend John Trusler (a publisher and polymath as well as clergyman) in which he outlined a theory of alienation that might have been written by Karl Marx. He observed: “To the Eyes of a Miser a Guinea is more beautiful than the Sun & a bag of Money has more beautiful proportions than a Vine filled with Grapes. . . . As a man is So he Sees.”13 (In Blake’s time, common nouns were frequently capitalized in written English, as in German, along with other words that writers felt to be of importance.) Half a century later, Marx wrote: “Private property has made us so stupid and one-sided that an object is only ours when we have it—when it exists for us as capital, or when it is directly possessed, eaten, drunk, worn, inhabited, etc. . . . In the place of all physical and mental senses there has therefore come the sheer estrangement of all these senses, the sense of having.”14 For Marx as for Blake, real freedom can arrive only when people are able to use their minds and senses—their imaginations—to change the world.

Blake’s style of drawing and painting was as radical as his subjects. It was a mash-up of influences, ranging from Hellenistic statuary, Gothic tomb sculpture, Dürer, Michelangelo, and, unusually, children’s books, as well as the popular broadsheets and tavern signs he would have seen every day in London. His Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794)—a pair of books exploring childhood delight in a harmonious world and the dawning recognition of its corruption—feature lyrics suggestive of lullabies and images recalling those in chapbooks, fable books, and alphabet books. Songs of Innocence features a poem, “Holy Thursday,” about children from London charity schools marching into St. Paul’s Cathedral and singing songs of praise for their benefactors. It begins innocently enough:

Twas on a Holy Thursday their innocent

faces clean

The children walking two & two in red &

blue & green15

Tate, London.

The illustrations at top and bottom appear to be equally ingenuous. The boys above face right; the girls below, left; and both groups are treated simply, almost without perspective. But the last lines of the poem are more barbed, with “aged men wise guardians of the poor” sitting beneath the singing children, offering them “pity.” Are the old men truly wise, and is pity the appropriate sentiment? In light of the last lines (and of a darker companion poem by the same title in Songs of Experience), the procession of innocents begins to resemble a forced march, especially when compared to the expressive freedom of the interlinear decoration on the page, with its vines, tendrils, and other foliage, and the suggestion of birds in flight.

If the illustrations for the “Songs” suggest carefully cultivated simplicity (masking critical incisiveness), Blake’s independent monoprints, watercolors, and tempera paintings often exhibit great complexity and sophistication. In The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (ca. 1795), we see a seated Enitharmon—a character in Blake’s mythology—draped in black from breasts to feet and shielding two kneeling nudes. She holds open a book decorated with a riot of abstract forms, while, at her side, a donkey grazes, an owl perches, and a reptilian creature looks upward. At the upper right, a monstrous bat hovers, the image anticipating Francisco Goya’s famous etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799).16 The work is one of Blake’s large color-printed drawings, for which he employed a transfer process akin to the decalcomania technique Surrealist Max Ernst later used. Blake would create a composition using colored inks on cardboard, place a dampened sheet of paper on top, and put the combination through a press. When he removed the sheet, the pigment, due to suction effects, would form an irregular, mottled surface. (See, for instance, Enitharmon’s book and the hill behind her.) He would then revise the printed composition using watercolor and ink, adding contour and clarifying forms. The final pictures are at once automatist (having relied partly on chance operations) and highly intentional.

ALTHOUGH BLAKE’S SOLDIER-PUNCHING incident and narrow escape from imprisonment shook him to the core, he was neither idle nor defeated afterward. He completed the illuminated books Milton a Poem (1804–11) and Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion (1804–20), his monumental final work in this medium. In addition, he produced hundreds of watercolors and tempera paintings, singly and in series, dedicated to, among other subjects, Milton, Bunyan, Dante, Shakespeare, and the Book of Job.

The only exhibition Blake had in his lifetime was held in 1809 in his family’s haberdashery shop. It was a fiasco. Few saw it, nothing sold, and the only critic to review it described the artist as an “unfortunate lunatic.”17 Its centerpiece was a pair of paintings dedicated to Prime Minister William Pitt and the British naval hero Lord Nelson: The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth (ca. 1805) and The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan (ca. 1805–09). Both are strange allegories that present their subjects as monsters, or as accomplices of monsters. In the Tate retrospective, these works were shown in a gallery intended to re-create part of Blake’s historic exhibition. They were periodically illuminated by colored spotlights that unfortunately made the works seem like holograms of themselves, and undercut their impact.

Yale Center for British Art.

In Blake’s final extant letter, written to his friend George Cumberland in April 1827, he upheld Republicanism (the right of the people to choose their own leaders) and protested the conformism of most Englishmen: “A happy state of Agreement to which I for One do not Agree.” He also noted: “I have been very near the Gates of Death & have returned very weak . . . but not in Spirit and Life not in The Real Man The Imagination which Liveth for Ever.” Blake died on August 12, 1827. His wife, who helped him with the printing and coloring of his illuminated books, while also performing domestic duties, died four years later. Blake’s supposed friend, the artist Frederick Tatham, immediately took charge of the estate and burned some of Blake’s manuscripts. He did this, according to a contemporary art collector, at the behest of a clergyman who said the works were created “under the instigation of the Devil.”18

Blake’s radicalism was invisible for a period after his death. However, by the late 1840s, a rediscovery was underway, and within a decade, he was championed by the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers, including Rossetti, William Morris, and A.C. Swinburne. Their artistic enthusiasm was propelled by the radical Chartist movement and the uprisings of 1848, which agitated for greater political enfranchisement and economic justice for the working class. A little later, the American Walt Whitman, fired by the catastrophe and emancipation effected by the Civil War, embraced the energy and insistent sexuality found in Blake’s poetry. Then there were the poets and novelists W.B. Yeats and James Joyce in Ireland and the Bloomsbury Group in England, who took up Blake during the first, tumultuous decades of the twentieth century. The English Neo-Romantic artists, including Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, and Keith Vaughan, found inspiration in Blake during the dark years of the Great Depression. And finally, in the postwar US, Blake was acclaimed by writers and artists associated with the Beats and the 1960s counterculture. (Ginsberg’s whole career may be seen as a footnote to Blake’s.)19 Radical movements for economic, political, sexual, or artistic freedom, in other words, have frequently upheld and even emulated Blake’s poetry and art. And we can expect that pattern to continue in the future. The question now is whether the recent attention accorded Blake, as evidenced by the massive Blake exhibition at Tate and another opening this summer at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, portends a wide-ranging social and political awakening or merely serves as one more form of mass entertainment in a neoliberal order dedicated to limiting imagination and indefinitely forestalling revolutionary change.

1 E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, London, Gollancz, 1963, p. 375. See also George Rudé, Ideology and Popular Protest, 1980, Chapel Hill, N.C., and London, University of North Carolina Press, 1995, p. 92; and J.A. Jaffe, “The ‘Chiliasm of Despair’ Reconsidered: Revivalism and Working-Class Agitation in County Durham,” Journal of British Studies 28, no. 1, January 1989, pp. 23–42.

2 See Peter H. Lindert, “When Did Inequality Rise in Britain and America?” Journal of Income Distribution 9, no. 1, Summer 2000, pp. 11–25; and Peter King, “Social Inequality, Identity and the Labouring Poor in Eighteenth-century England,” in Identity and Agency in England, 1500–1800, ed. Henry French and Jonathan Barry, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

3 William Cobbett, Rural Rides, London, William Cobbett, 1830, p. 183.

4 The precise origin of the term is unknown, but numerous journalists in the UK and US have invoked it. See Sarah O’Connor, “Left behind: can anyone save the towns the economy forgot?” FT Weekend Magazine, Nov. 16, 2017, ft.com; Will Hutton, “The bad news is we’re dying early in Britain—and it’s all down to ‘shit-life syndrome,’” Guardian, Aug. 19, 2018, theguardian.com; and Bruce E. Levine, “‘Shit-Life Syndrome,’ Trump Voters, and Clueless Dems,” CounterPunch, Jan. 3, 2020, counterpunch.org. Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn wrote about US “deaths of despair” in “Who Killed the Knapp Family?” New York Times, Jan. 9, 2020, nytimes.com.

Yale Center for British Art.

5 W.J.T. Mitchell, “Dangerous Blake,” Studies in Romanticism 21, no. 3, Fall 1982, pp. 410–16.

6 Mark Crosby, “‘A Fabricated Perjury’: The [Mis]Trial of William Blake,” Huntington Library Quarterly 72, no. 1, March 2009, p. 32.

7 William Blake, annotations to Francis Bacon’s Essays Moral, Economical and Political, 1798, in Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1970, p. 612.

8 See Robert N. Essick, William Blake, Printmaker, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1980; Joseph Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1993; and Michael Phillips, William Blake: Apprentice & Master, Oxford, U.K., Ashmolean Museum, 2014, pp. 89–105.

9 William Blake, “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” 1794, reprinted in Poetry and Prose of William Blake, p. 39.

10 Ibid., pp. 35–36.

11 See Stephen F. Eisenman, William Blake and the Age of Aquarius, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 2017.

12 S. Foster Damon, A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake, rev. ed., ed. Morris Eaves, Hanover, N.H., and London, University Press of New England, 1988.

13 Letter from William Blake to Rev. Dr. Trusler, Aug. 23, 1799, in Poetry and Prose of William Blake, p. 676.

14 Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, marxists.org.

15 William Blake, “Holy Thursday,” Songs of Innocence, 1789, reprinted in Poetry and Prose of William Blake, p. 13.

16 There is no chance, however, that Goya could have seen Blake’s watercolor. He never traveled to England and Blake’s watercolor was not engraved.

17 The full review can be found in Blake Records, ed. G.E. Bentley Jr., Oxford, U.K., Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 282–85.

18 The episode is described in Leo Damrosch, Eternity’s Sunrise: The Imaginative World of William Blake, New Haven, Conn., and London, Yale University Press, 2015, p. 269.

19 Eisenman, pp. 26–41.

This article appears under the title “Rouse Up, O Young Men of the Neoliberal Age!” in the March 2020 issue, pp. 38–45.

[ad_2]

Source link