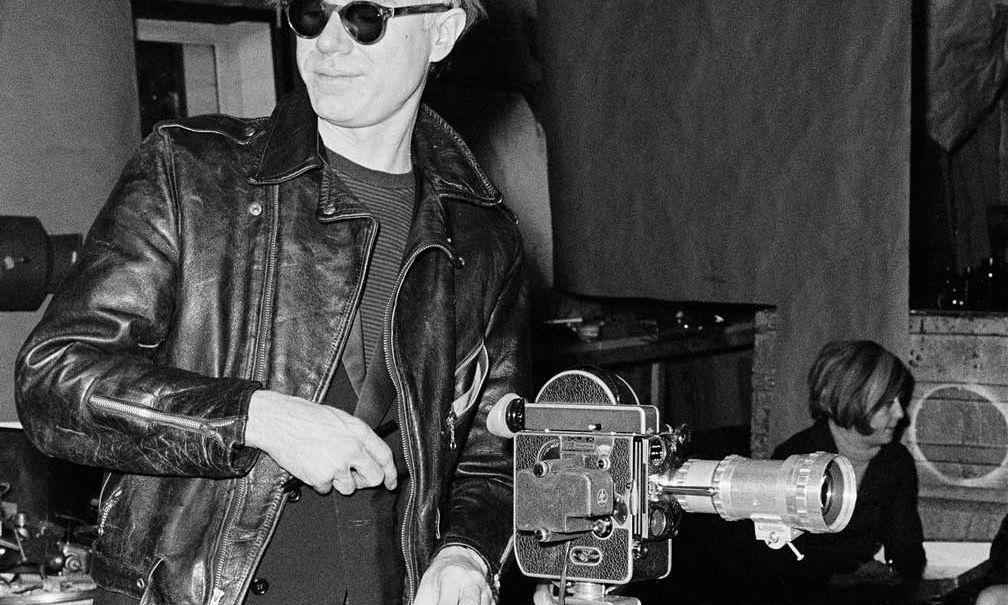

Andy Warhol was famously a fan of art as business and believed that good business was a work of art in itself. How might he feel about his namesake museum’s ambitious Pop District project in his hometown of Pittsburgh?

Photo: Santi Visalli/Getty Images

In the parable of the blind men and the elephant, a group tries to figure out what the creature could possibly be based on touch alone. The man next to its ear thinks it is a fan. The one by its trunk calls it a snake. “No, it’s a wall,” says the man who touches its side.

Pittsburgh’s Andy Warhol Museum does have an elephant sculpture in its collection, Keith Haring’s Untitled (Elephant) (1985), but the elephant that many in the art world have been attempting to figure out there is the Pop District. The museum’s ten-year, $80m project includes a performance venue, workforce-development programme and series of public art installations spanning several city blocks around itself in the North Shore neighbourhood—home to the city’s baseball field and largest concert venue.

Although the Pop District began in earnest in May 2022, the Warhol has yet to break ground on its new building—a rendering of the performance venue shows a shining, white multiplex that looks like a cross between a department store and a co-working space. The past two years have been quite rocky. In 2023, the museum hired a new chief curator, Aaron Levi Garvey, who departed after only a few months following controversy over a wall text for Warhol’s Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century that some described as “soft Zionist” in the context of the Israel-Hamas war. The museum’s director, Patrick Moore, left abruptly earlier this year. People questioned whether the Warhol’s focus on a nebulous, multi-pronged, multimillion-dollar project had contributed to internal discontent.

The Pittsburgh public radio station WESA reported last December on discord inside the museum over the Pop District and what some saw as a focus on fundraising over curation. This had already resulted in the exit of several director-level staff members in less than a year. One anonymous employee summed it up for WESA: “The museum has been taken over by the alien that is the Pop District.”

Steven Knapp, the president of the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh (which oversees the Warhol), has stressed that Moore’s departure had nothing to do with the controversy around the Pop District. But the Warhol only has a $20m endowment, and the Pop District’s public relations kerfuffle has emphasised how it is a small institution saddled with a big, expensive idea.

In what appears to be an effort to drum up support from a sceptical community, the Warhol recently released an economic impact assessment with data to back up the Pop District’s planned performance venue, the Factory. This is the project’s most elusive element, and the one that promises the most lucrative financial return. (When Moore spoke to WESA last year, he said he hoped the Factory would help balance out losses from a reduction in income from loans, due to many works now being too old or fragile to travel.) “Change creates tension, but change is necessary,” reads a cryptic publicity text accompanying the report. “The status quo is telling on itself. We are not the status quo.”

Dan Law, the associate director of the Warhol who also oversees the Pop District, describes the project’s goals as “ambitious but realistic”. Those goals? “To attract 75,000 new visitors to the North Shore through live performance and events, generate significant economic impact, support jobs in Pittsburgh’s creative sector and beyond, produce 150-plus live performances and events annually and, most importantly, provide valuable earned income to help sustain the Warhol and its mission for years to come,” he writes in the introduction to the report.

The museum’s assessment focuses on contributions to the local economy from out-of-towners, pointing out that local visitors to the Warhol and its various projects already contribute to Pittsburgh’s economy. According to the report, the Factory will have a total direct economic impact of $17.6m per year—more than half of that coming from non-local visitors. The report also states that the venue will create 126 jobs and generate $6.2m in labour income. The building’s construction itself is expected to generate an estimated 339 jobs and $58.5m for the city of Pittsburgh. If all goes well, Law expects a groundbreaking in late spring or early summer next year.

Much of the Pop District’s revenue rests on the Factory. Law, who once ran a music festival in Pittsburgh called Thrival, has a passion for live performance that comes through in his descriptions of the Factory. He envisages it as analogous to the 9:30 Club—a much-loved independent music venue in Washington, DC—and he points to excitement about a growth in Pittsburgh’s music scene. And yet, although the venue will use the name of Andy Warhol’s legendary Manhattan studio, it is unclear how it relates to the artist himself. (Warhol was famously involved with bands like the Velvet Underground and the Rolling Stones, but these connections do not seem to play a part in the project.)

The Warhol Academy, the Pop District’s workforce-development programme, on the other hand, already has a physical space next to the museum. In 2023, the academy generated $1.5m in wages, stipends, fellowships and honoraria. It grants diplomas through Pennsylvania’s department of education, and it schedules classes and workshops at convenient times for working people in the community. Through the programme, Law and his team have focused on creating free and accessible classes in videography, social-media marketing and editorial and communication skills.

The Warhol Academy, part of the Pop District project, provides education and training for Pittsburgh locals

Photo: Camila Casas

RJ Kozain, a Pittsburgh-based electronic musician who performs under the name 2020k, is currently taking a class at the academy. “I can’t tell if Andy would be rolling over in his grave or not with how corporate it feels in there,” he tells The Art Newspaper. (“Maybe I should just go ask him,” he adds—Kozain lives close to where Warhol is buried in Bethel Park.) As for the Factory and its potential for Pittsburgh’s music scene, “I prefer to watch institutions walk the walk first,” Kozain says. “The prospect of building infrastructure to bring talent into Pittsburgh is always exciting to me, and I hope that the venue finds ways to adequately foster local talent.”

News of the Factory’s potential impact comes on the heels of the cancellation of Sudden Little Thrills—a huge, Live Nation-funded Pittsburgh music festival—which left locals disappointed that either the city has no interest in supporting such an event or Live Nation has no interest in Pittsburgh. “We may have to accept to some degree that Pittsburgh might not be a ‘festival city’,” Law says, “but it could be a venue city, a four-wall city focused on consistent year-round programming.”

Law stresses that he wants to be as open as possible with the media and community stakeholders about the Pop District as a whole. “I started the Pop District, but it does not get anywhere without enormous amounts of buy-in from everyone,” he says.

As Andy Warhol himself once said: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art, and working is art, and good business is the best art.” Whether the Pop District turns out to be good business, and good art, remains to be seen.