[ad_1]

For her sprawling history “Face: A Visual Odyssey,” designer and author Jessica Helfand assembled a dazzling cabinet of human curiosities. From police mugshots and dating-site selfies, to politicians’ headshots, Victorian death portraits and rubberised sex-dolls — all to grapple with the way our faces have been presented and judged over the centuries — and the lengths we’ve gone to, to “improve” them.

We have long tried to tweak the features nature dealt us, whether with magic creams, gadgets or exercise (even Cleopatra practiced face yoga). But today, when approximately two billion images are uploaded every day to social media — nearly 100 million of which are estimated to be selfies, according to Helfand — the pressure to appear beautiful has never been higher.

Allied Newspapers, Limited Fortune Telling for Everyone Credit: Allied Newspapers/MIT Press

“We’re so quick to judge and measure, and having cryptic ways of comparing ourselves to each other is unfortunately on the rise,” Hefland said. “I think particularly for young people, the traffic and use of your face as a form of currency to gain likes and popularity struck me as really not where civilization needed to be going.”

As Helfand notes in the book, the selfie has powered a global beauty industry valued at $532 billion, driven by our desire to share images on social media — “the world’s creepiest popularity contest” as Helfand puts it. A proliferation of apps that can morph our features in seemingly unlimited ways has fueled our desire to experiment. There are playful ones that transform us into koalas or zombies, or blend our faces with our favorite celebrities; and apps that airbrush skin, alter eyebrows, noses, lips, and even change our perceived gender or race.

Cosmetic procedures are also booming, with some thanks to the selfie: In 2017 there was a 55% increase in nose jobs according to the American Academy of Plastic Surgeons. “The uptick in people wanting nose jobs was very much a function of people saying they didn’t like the way their noses looked in selfies,” Helfand said.

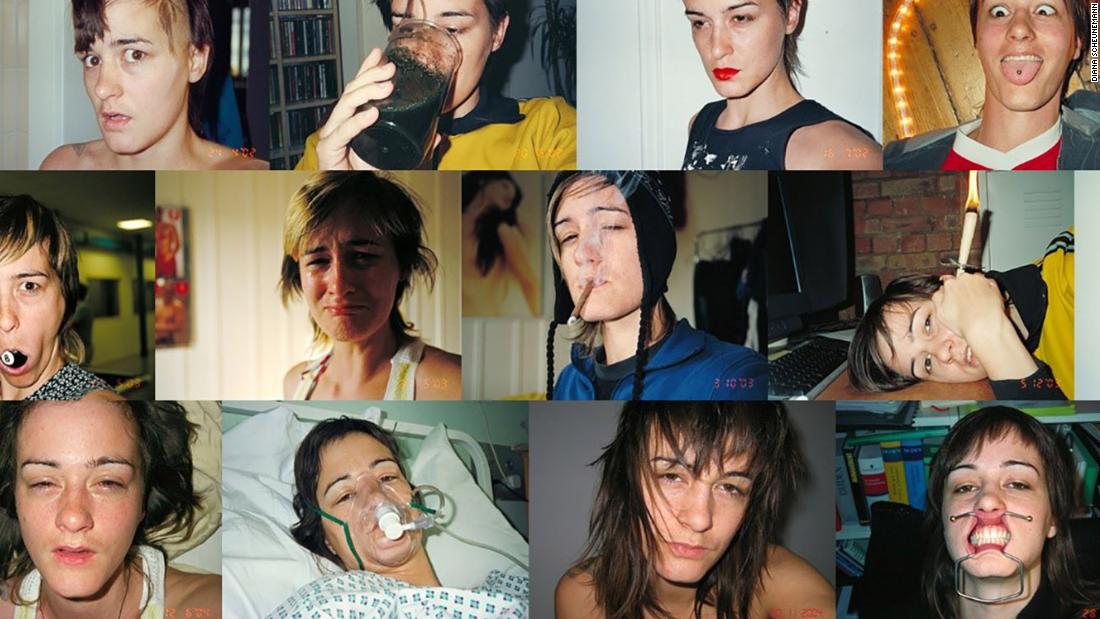

Photos from “Behind My Face” (1999-present) by Diana Scheunemann. Scheunemann has been taking a self-portrait every day since 1999. Credit: Diana Scheunemann/MIT Press

While it may seem as though our increasingly visual culture is pushing us ever closer to conformity, Helfand sees areas of positive change, too. For generations we have failed to protect and preserve non-Western images, leading to a dearth of diversity in surviving archives. Today, with 3.5 billion smartphone users in the world, we now have easy access to a kaleidoscope of faces online as we become our own archivists.

But has this increased representation led to more inclusive beauty standards? Hefland isn’t so sure. “I wish I could say yes,” she said. “I think it’s less binary and of course there are many more outlets for showing different faces, different bodies… Beauty standards take a much longer time to change, but I’d like to think an increase in tolerance may be one of the few positive pieces of collateral damage from technology. There is some wiggle room in our expectations — we don’t all have to look like Nefertiti.”

A photo of a girl with a “Utrechtse Krop” (Utretch goiter) — a thyroid condition common in the Dutch city in the 19th century, when local drinking water was deficient in iodine. Credit: Troost/MIT Press

Above all, Helfand says her time spent sifting through human features has shown her our drive to connect. “Why are we all doing Zoom meetings now? Because we’re reassured by seeing other people’s faces, their lips move and their voices connected to a person,” she said.

“Passport Don’ts” (2017) by Nadia Gohar. Gohar created a series of “flawed” passport photos to questions notions of prejudice when it comes to self-presentation. Credit: Nadia Gohar/MIT Press

“One of the things I learned from spending two years looking at faces is that when you look at someone else’s face, you have to look squarely at your own reflection. You’re looking at humanity when you look at faces. It isn’t about the one person who is as pretty as Kim Kardashian West, it’s about connecting to a much deeper humanity. That gives me hope. If more people could start to think about their faces as connectors, as a litmus test to a deeper human truth, then this book will have had some impact.”

Top image: “Ajak (Turquoise)” from “How We See” (2015) by Laurie Simmons

[ad_2]

Source link