[ad_1]

As the sexist and racist attacks against Kamala Harris pile on, there’s one line of criticism that is particularly ripe for debunking. That’s the idea that Harris, Joe Biden’s running mate for president, is some kind of “affirmative action hire,” chosen not on her merits but as a “box-checking exercise for the ‘woke’ crowd,” as Fox News’ Laura Ingraham put it.

The implication here is that Harris isn’t qualified for the role. Of course that’s absurd.

Harris has more than a decade of experience at the highest levels of government, including as San Francisco district attorney, California attorney general and as a senator from the most populous state in the country. She’s proven herself on the national stage, especially in her role on the Judiciary Committee, where she won plaudits for her skillful questioning of Trump appointees.

But like most women of color — Harris is both Black and Asian American — she has had to work harder to get to where she is than white men in comparable positions. One example: the current president, who’d never held public office prior to his election. This dynamic was made plain at the start of the Democratic presidential primary when Harris ran against a one-term congressman, the mayor of a small city and several rich guys with no political experience, nearly all of them white.

The reality is: The deck is stacked against women of color, and particularly Black women, in this country. The ones who make it to the top, like Harris, overcome an astonishing array of obstacles.

Gender played a role in the selection of both Kamala Harris and Tim Kaine. But only in Harris’ case was there speculation that she was unqualified.

That’s true in politics, where Black women, despite some recent incredible gains, are still woefully underrepresented. There’s never been a Black female governor in the U.S. There have only been two Black female senators, one of whom is Harris. If Biden and Harris win, there might be no Black women in the Senate next year.

To understand better what Black women are up against, look at the American workplace, a maze of bias and discrimination that can leave all women feeling burned out, beaten down and disheartened.

For Black women though, it’s worse. “I don’t think people understand how constant and numerous the barriers facing Black women are at work,” said Raena Saddler, a vice president at Lean In, the women’s advocacy group.

Black women have a harder time getting hired, getting promoted and face more outright discrimination, notes a report Lean In released this week.

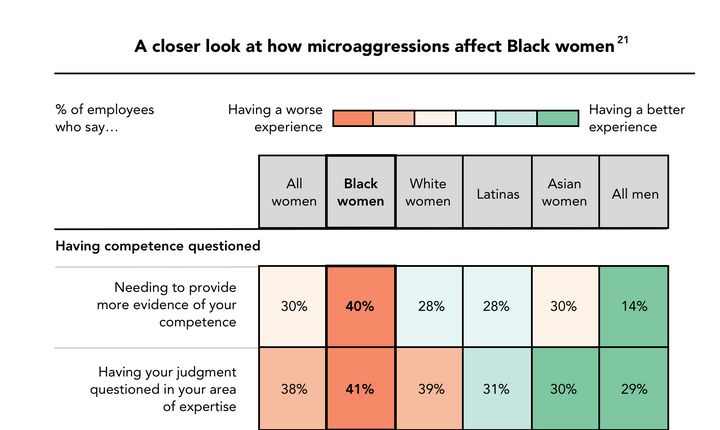

They get little benefit of the doubt from colleagues. Forty percent of Black women surveyed by Lean In say they need to provide more evidence to prove they’re competent at work, compared to 28% of white women and 14% of all men. About the same percentage of Black women say that their judgment is questioned in their area of expertise, versus 39% of white women and 29% of all men.

One in four black women has heard someone express surprise at work at their “language skills,” compared to 1 in 10 white women, according to the survey.

Black women at work are also often stereotyped as “angry.” That perception, while incorrect, means they’re more likely to get poor evaluations from supervisors, according to a recent study by the Academy of Management highlighted by Lean In. Those bad reviews hold them back.

The “angry woman” attack is a favorite of Donald Trump, who just this week accused Harris of being angry and “a mad woman” at the 2018 Senate hearing for Brett Kavanaugh. Of course, it was Kavanaugh whose anger was on full display back then.

“Kamala Harris has worked harder. She’s done everything – Local office, statewide office, federal office, now being named to the highest office. The best schools. Everything,” said Glynda Carr, CEO and co-founder of Higher Heights for America, a group that advocates for Black women in politics. “And still the perception of her, for many, is ambitious, angry and nasty.”

For Black women to get ahead in politics, Carr said, “We have to work longer and harder than our counterparts who are less qualified, less experienced.”

The issue has to do with people’s perception of what a leader looks like, she added.

The myths about anger and competency lead to constant pressure to prove yourself, which means it takes more work and more experience to get promoted or rise up to the top.

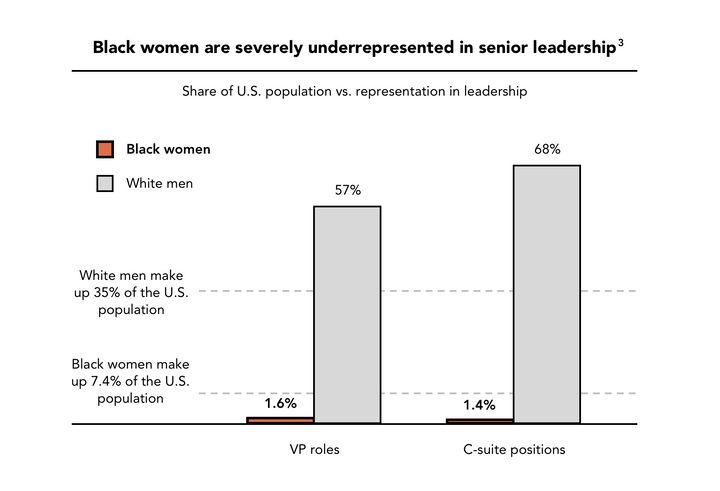

And, no surprise, fewer Black women get the nod up the ladder: Only 1.4% of C-suite roles (the top “chief” slots at companies) are held by Black women, though they make up 7.4% of the U.S. population. White men hold 68% of those jobs, and they make up 35% of the population. There are no Black female CEOs in the Fortune 500.

Lean In found that the problem starts right away. Companies might hire a number of women of color for entry-level roles, but then fail to promote them at the same rate as men.

For one survey, the group looked at men and women getting promoted for the first time to management. For every 100 men promoted to manager, only 58 Black women advanced, according to the findings.

“That’s a massive gap,” Saddler said. “All these people were talented and bright enough to be hired in the first place, and no one has ever managed before. You’d have to see men as inherently qualified to be managers. Unlikely. Or there’s massive bias and racism here.”

Getting the job is harder, too.

Forget about promotions; just landing a job is harder for Black women.

Claudine Moore, a Black woman who’s worked in marketing and public relations for decades, told HuffPost about the time that she had to interview with around 15 different people to get a senior manager role at one agency.

An average candidate would have three or four interviews, said Moore, who now runs her own marketing and media firm and teaches at New York University, but when you’re considered a “diversity” hire, there’s more thorough vetting, she said.

Still, she jumped through those hoops and got a job offer. Or so she thought. After the offer was in place, Moore was asked to take one last meeting with a manager at the company. A formality, she was told.

“When I walked into his office, as soon as he saw me, the blood drained from his face,” she recalled recently. “I knew he didn’t want me to have the role.”

Moore remembers the interview feeling combative. He questioned her background in a way that made clear that he doubted her experience. “So you really worked at this agency?” she remembered him asking. “Almost disbelief.”

Soon after that, the company called her back. It was rescinding the offer. “People don’t really believe these situations happen until these things play out in front of their eyes,” she said.

That was one of a myriad of anecdotes Moore shared. She also recounted the time she inherited a white male assistant who clearly wasn’t comfortable working for her. Or the time a male colleague had a noose in his cubicle for decoration, and when she complained, human resources said “he didn’t mean anything by it,” she said. “That was in New York City in 2007. It wasn’t 50 years ago in Kentucky.”

“All the companies I’ve been with, you’re treated a lot harsher than everybody else,” she said.

No one said Tim Kaine was chosen because he’s a man.

In spite of all these obstacles, and the true grit and determination it takes to overcome them, when Black women do succeed at work and in politics, their achievements are often discounted, the Lean In report points out. Often, their peers, or tiresome Laura Ingraham types, won’t give them credit for their work.

Colleagues might say, “She only got the promotion because she’s Black,” the Lean In report notes. Or because she’s a woman.

“When these comments go unchallenged, they can prevent Black women from receiving the credit they deserve for their hard work and achievements,” the report notes.

That’s what’s happening with Harris. It likely didn’t help that Biden explicitly announced he would choose a woman as a running mate back in March, because it created the perception that gender was the only factor in his choice.

But it’s worth digging in here: Candidates for years have only chosen men as running mates (with two prior exceptions). Did they only get picked because they were men?

When Hillary Clinton was preparing to announce her choice for vice president, she never came out and said, “I will choose a man.” But it was understood that the first woman running for president on a major party ticket would choose a guy as a running mate to balance out the ticket. (Similar to how Barack Obama was expected to choose a white person as his running mate.)

No one went around arguing that Tim Kaine was unqualified for the role and was picked only because he was a man. Candidates have long chosen running mates as counterpoints to their own identity.

This is worth underlining: Gender played a role in the selection of both Harris and Kaine. But only in Harris’ case was there speculation that she was unqualified (when arguably, she is more prepared).

But in the political realm at least, things are changing, Carr said. She points to the rising power of Black female voters, something everyone finally woke up to in 2017 when Black women in Alabama helped defeat Roy Moore in his run for Senate.

“America woke up and said thank you, Black women, for saving democracy,” and Black women “stood a little taller” after that, realizing their power, Carr said.

Now more are running for office. A record number of women of color are slated to run for Congress in 2020.

“All these women have created this moment for Kamala Harris,” she said. “They led boldly, they jumped over man-made barriers.”

She added: “I do believe Black women are breaking through.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link