[ad_1]

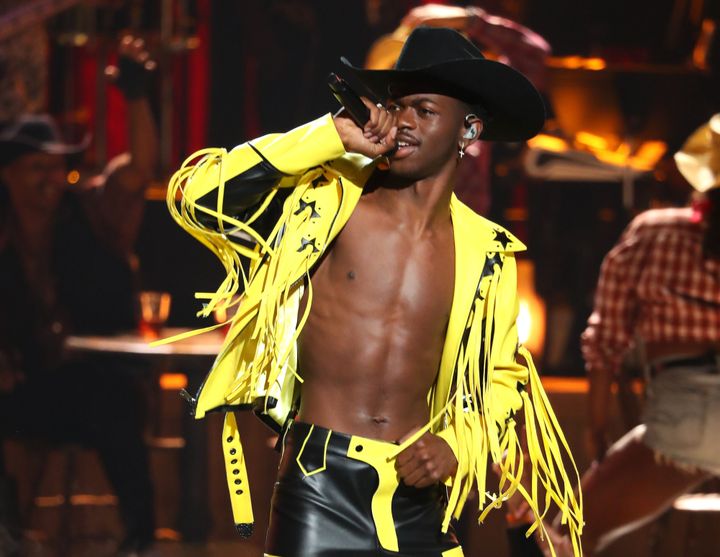

Country music listening numbers are on the rise. And yet, while black artists dominate charts across multiple genres, country music charts are a predominantly white space. So when Billboard removed Lil Nas X’s smash hit “Old Town Road” from its Hot Country Songs chart in March, some fans weren’t surprised.

In a statement to Rolling Stone, Billboard justified its decision, saying, “[Old Town Road] does not embrace enough elements of today’s country music to chart in its current version.” This begs the obvious follow-up question: What are the elements of country music?

Country legend Harlan Howard famously described a country song as “three chords and the truth.” But according to Alice Randall, the first black woman to pen a No. 1 country hit, a country song is actually made up of three chords and four very specific truths:

“Life is hard. God is real. Family, whiskey and road are significant compensations, and the past is better than the present,” said Randall, a bestselling author and a professor at Vanderbilt University. “That’s country. Three chords and those four truths.”

Music scholars often acknowledge the black musical influence on country music chords, pointing out things like the African origin of the banjo and the genre’s deep roots in blues music. But it’s the black influence on the four truths that often gets overlooked, and that’s also where “the racial fault line,” as Randall called it, lies in country music.

“Superficial country songs are just looking back in some vague way,” she said. “But a sense of hauntedness by the past actually creates a sense of responsibility in the present. Country acknowledges the past is still having an impact.”

This reflection on the past is perhaps the reason why conversations around race in country music strike a particularly resonant chord, even though there are similar conversations regarding other genres.

“Country music is a stand-in for a lot of conversations that we are too often afraid to have, or even when we want to have them, we don’t necessarily have the language to do so effectively,” said Charles Hughes, a music scholar and the director of the Lynne and Henry Turley Memphis Center at Rhodes College.

For example, when Beyoncé performed her song “Daddy Lessons” at the 2016 Country Music Association Awards alongside the Dixie Chicks, she faced backlash from some country fans who called into question her country bona fides. This further sparked the conversation around which artists get to call themselves “country,” and perhaps more to the point, which artists don’t.

“A lot of folks really celebrated [the CMA performance], not just as a really cool example of what country music could sound like, but also as potentially a symbol of the changing — or, at least, loosening — boundaries, in terms of who and what gets to be country,” Hughes said. At the same time, “the moment created that same old anger that we’ve seen too often about … what country music is supposed to represent in terms of race, in terms of gender, in terms of a certain kind of identity.”

Country music’s association with white identity goes back not just to the beginning of country music, but to the beginning of musical genre itself, Hughes said.

Starting in the 1920s, at the dawn of the recorded music industry and at the height of the Jim Crow era, record companies began marketing genres like gospel and blues specifically to black audiences as “race music” or “race records.”

The record industry marketed and promoted and created a language about the music from the beginning, and this continues through this day in some way, in which whiteness is, if not on the surface, then right below it.

Charles Hughes, music scholar

Meanwhile, white audiences were sold country music — or, as it was originally called, “hillbilly music.” The genre was musically and thematically rooted in the black American experience, and yet, it “was very explicitly thought of as being the music of white southerners or white folks who had recently moved out of the south into northern or western cities,” Hughes said.

Despite the work of black country artists like Charley Pride or Ray Charles’ seminal country album “Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music,” the genre has never quite lost its original racial designation.

“The record industry marketed and promoted and created a language about the music from the beginning, and this continues through this day in some way, in which whiteness is, if not on the surface, then right below it,” Hughes said.

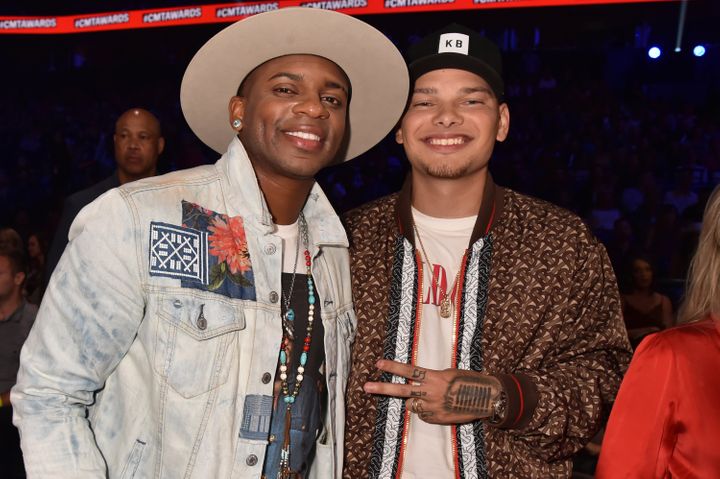

Still, there is reason to believe the genre could be changing. A new crop of diverse artists, including Jimmie Allen and Kane Brown, are making waves on the country music charts.

Allen grew up listening to country music in his hometown of Milton, Delaware, and he struggled for years in Nashville before breaking out with his debut album “Mercury Lane” in 2018. When the album’s first single, “Best Shot,” rose to the top of Billboard’s country music chart, he became the first black artist to land a career No. 1 country debut. For Allen, the achievement was bittersweet.

“People started saying, ’Well you’re the first black artist to have a debut country number one. I was like, ‘that’s great,’” he said. “But it quickly went from great to being like, man, it kind of sucks. We’re in 2019 and we’re still talking about color. It’s the only genre where we talk about it.”

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link