[ad_1]

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah — The lunch rush at St. Vincent de Paul Dining Hall is a snapshot of the changing character of American homelessness.

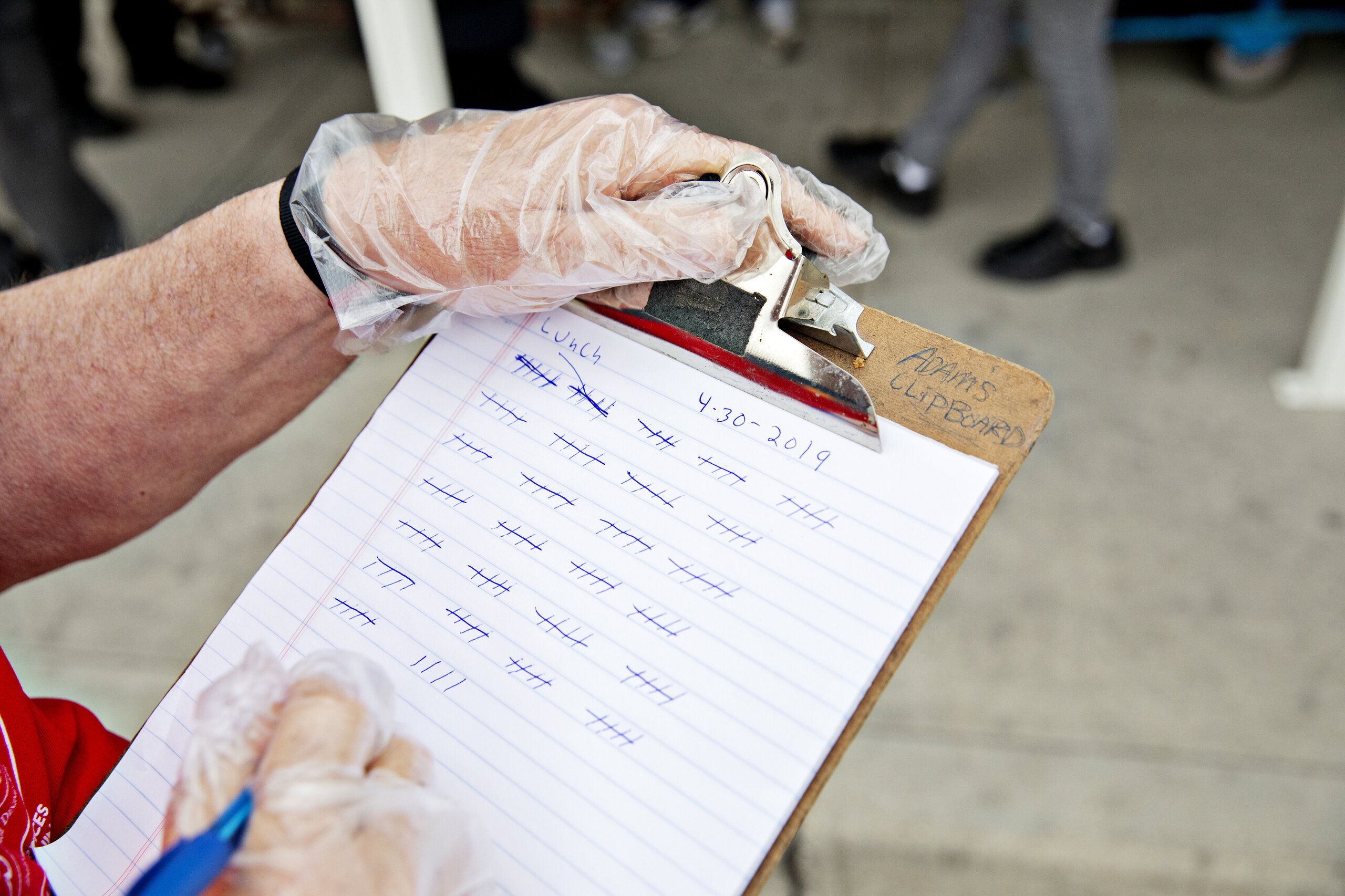

The first thing that strikes you is the sheer number of people the soup kitchen serves. The line outside starts forming two hours before the food is ready. Diners file in, eat quickly and get up as soon as they’re finished. They know someone is waiting outside for their seat.

Even more striking than the scale of need are the shifting demographics of who is eating here and why. The homeless population is getting younger, staffers say, and more likely to have children and full-time jobs. In one hour, over taco salad and Fanta, I meet fast-food employees, a former car salesman who lost his home in the financial crisis and a pregnant 31-year-old whose baby is due the same month her housing vouchers run out.

But the biggest surprise about St. Vincent’s may be the state in which it’s located. Just four years ago, Utah was the poster child for a new approach to homelessness, a solution so simple you could sum it up in five words: Just give homeless people homes.

In 2005, the state and its capital started providing no-strings-attached apartments to the “chronically” homeless — people who had lived on the streets for at least a year and suffered from mental illness, substance abuse or a physical disability. Over the next 10 years, Utah built hundreds of housing units, hired dozens of social workers ― and reduced chronic homelessness by 91 percent.

The results were a sensation. In 2015, breathless media reports announced that a single state, and a single policy, had finally solved one of urban America’s most vexing problems. Reporters from around the country came to Utah to gather lessons for their own cities. In a widely shared “Daily Show” segment, Hasan Minhaj jogged the streets of Salt Lake City, asking locals if they knew where all the homeless people had gone.

But this simplistic celebration hid a far more complex truth. While Salt Lake City targeted a small subset of the homeless population, the overall problem got worse. Between 2005 and 2015, while the number of drug-addicted and mentally ill homeless people fell dramatically, the number of people sleeping in the city’s emergency shelter more than doubled. Since then, unsheltered homelessness has continued to rise. According to 2018 figures, the majority of unhoused families and single adults in Salt Lake City are experiencing homelessness for the first time.

“People thought that if we built a few hundred housing units we’d be out of the woods forever,” said Glenn Bailey, the executive director of Crossroads Urban Center, a Salt Lake City food bank. “But if you don’t change the reasons people become homeless in the first place, you’re just going to have more people on the streets.”

This is not just a Salt Lake City story. Across the country, in the midst of a deepening housing crisis and widening inequality, homelessness has concentrated in America’s most prosperous cities. So far, municipal leaders have responded with policies that solve a tiny portion of the problem and fail to account for all the ways their economies are pushing people onto the streets.

The reality is that no city has ever come close to solving homelessness. And over the last few years, it has become clear that they cannot afford to.

Eric (not his real name) is exactly the kind of person Utah’s policy experiment was intended to help. He is 55 years old and has been homeless for most of his life. He takes medication for his schizophrenia, but his paranoia still leads him to cash his disability checks and hide them in envelopes around the city. When he lived on the streets, his drug of choice was a mix of heroin and cocaine. These days it’s meth.

Despite all his complications, Eric is a success story. He lives in a housing complex in the suburbs of Salt Lake City that was built for the chronically homeless. He has case workers who ensure that he takes his medications and renews his benefits. While he may never live independently, he is far better off here than in a temporary shelter, a jail cell or sleeping on the streets.

The problem for policymakers is that Eric is no longer emblematic of American homelessness. In Salt Lake City, just like everywhere else, the population of people sleeping on the streets looks a lot different than it used to.

As the economy has come out of the Great Recession, America’s unhoused population has exploded almost exclusively in its richest and fastest-growing cities. Between 2012 and 2018, the number of people living on the streets declined by 11 percent nationwide — and surged by 26 percent in Seattle, 47 percent in New York City and 75 percent in Los Angeles. Even smaller cities, like Reno and Boise, have seen spikes in homelessness perfectly coincide with booming tech sectors and falling unemployment.

In other words, homelessness is no longer a symbol of decline. It is a product of prosperity. And unlike Eric, the vast majority of people being pushed out onto the streets by America’s growing urban economies do not need dedicated social workers or intensive medication regimes. They simply need higher incomes and lower housing costs.

“The people with the highest risk of homelessness are the ones living on a Social Security check or working a minimum-wage job,” said Margot Kushel, the director of the UCSF. Center for Vulnerable Populations. In 2015, she led a team of researchers who interviewed 350 people living on the streets in Oakland. Nearly half of their older interviewees were experiencing homelessness for the first time.

“If they make it to 50 and they’ve never been homeless, there’s a good chance they don’t have severe mental illness or substance abuse issues,” Kushel said. “Once they become homeless, they start to spiral downward really quickly. They’re sleeping three to four hours a night, they get beat up, they lose their medications. If you walk past them in a tent, they seem like they need all these services. But what they really needed was cheaper rent a year ago.”

Other research has found the same connection between housing costs and homelessness. In 2012, researchers found that a $100 increase in monthly rent in big cities was associated with a 15 percent rise in homelessness. The effect was even stronger in smaller cities.

“Once you’re homeless, it’s a steep hill to climb back up,” Bailey said. “When an eviction is on your record, it’s even steeper. And even if you do get back into housing, you’re still one illness or one car problem away from becoming homeless again.”

And rising affluence isn’t just transforming the economic factors that cause homelessness. It is also changing the politics of the cities tasked with solving it. Across the country, as formerly poor neighborhoods have gentrified, politicians are facing increasingly strident calls to criminalize panhandling and bulldoze tent encampments. While city residents consistently tell pollsters that they support homeless services in principle, specific proposals to build shelters or expand services face vociferous local opposition.

“The biggest hindrance to solving homelessness is that city residents keep demanding the least effective policies,” said Sara Rankin, the director of the Homeless Rights Advocacy Project at Seattle University School of Law. The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that punishing homeless people makes it harder for them to find housing and get work. Nonetheless, the most common demands from urban voters are for politicians to increase arrests, close down soup kitchens and impose entry requirements and drug tests in shelters.

“Homelessness is a two-handed problem,” Rankin said. “One hand is everything you’re doing to make it better and the other is everything you’re doing to make it worse. Right now, we spend far more effort undoing our progress than advancing it.”

No municipality demonstrates this dynamic better than Salt Lake City. Thanks to rising housing and construction costs, the building of new homeless housing has slowed to a trickle. A plan to replace the city’s central homeless shelter with a handful of smaller, suburban facilities has been delayed and scaled down due to neighborhood opposition. In 2017, after years of demands by downtown residents and businesses, Utah initiated a $67 million law enforcement crackdown on the population sleeping on the streets of its state capital. In its first year, the campaign resulted in more than 5,000 arrests — and just 101 homeless people being placed into housing.

And there are no signs that it’s going to get better. The economy is creating new homeless people faster than cities can house them. And the worse the problem gets, the harder it becomes to solve.

“The entire system has stalled,” said Andrew Johnston, the vice president of program operations for Volunteers of America Utah, one of the largest service providers in Salt Lake City. “As the economy has improved, policymakers seem to believe that the market will supply affordable housing on its own. But if you don’t put public and private money into it, you’re not going to get it.”

Three years after she escaped from homelessness, Georgia Gregersen’s most enduring memory is how quickly she fell into it.

“I’m a waitress, I’m at home with a new baby and three months later I’m sleeping in an empty parking garage,” said Gregersen, who now lives in a Salt Lake City suburb.

Her story plays out as a series of unraveling safety nets. She had been trying to get clean for years, but the waitlists for rehab were months long. She got on methadone when she found out she was pregnant, but it cost $85 per week, almost as much as she had been spending on heroin. After her son was born she was eligible for daycare vouchers, but the never-ending paperwork — “something was always wrong or required another appointment” — meant she never actually got them.

Eventually, the cost of childcare and the stress of being a single mom got to her and she relapsed. Within weeks she had lost her job and handed her son over to her parents. Her aunt, with whom she had been staying, asked her to move out.

Sleeping outside made her even more desperate to get clean, but everywhere she turned her options were cut off. Every halfway house and detox center in Salt Lake City was full. When she applied for subsidized housing, a government official told her it would take two years just to get on the waiting list.

“I thought, I’ll probably be dead by then,” she said.

Gregersen spiraled downward in 2015, right around the time Utah announced it had ended chronic homelessness. Unlike the recipients of that experiment — most of whom required 24-hour, lifelong support — Gregersen didn’t need permanent supportive housing. She needed every other form of support to be adequately funded and available when she needed it.

“We always look to one thing to be the answer,” she said, “but I needed everything, and in concert.”

Gregersen’s story perfectly encapsulates the challenge of urban policy in a changing and deteriorating America. Truly ending homelessness will require cities to systematically repair all the cracks in the country’s brittle, shattered welfare system. From drug treatment to rental assistance to subsidized child care, the only way to address the crisis is through a concerted — and costly — expansion of government assistance.

And yet, even as homelessness becomes a defining feature of urban growth, no city in America can afford to meaningfully address it.

“Politicians keep proposing quick fixes and simple solutions because they can’t publicly admit that solving homelessness is expensive,” Kushel said. Before the 1980s, she points out, most of the responsibility for low-income housing, rental assistance and mental health treatment fell on the federal government.

Since then, though, these costs have been systematically handed over to cities. Between 1980 and 1990, the number of low-income households receiving federal rental assistance dropped by more than half. Hundreds of thousands of mental health treatment beds have disappeared. Despite having far deeper pockets, the federal government now spends less per homeless person than the city of San Francisco.

The relentless localization of responsibility means that cities are spending more than they ever have on homelessness and, at the same time, nowhere near enough. L.A.’s recent $1.2 billion housing bond is one of the largest in American history. It will construct 1,000 permanent supportive housing units every year — in a city where 14,000 people need one. According to a 2018 analysis, Seattle would have to double its current spending to provide housing and services for everyone living on the streets.

Smaller cities have an even wider spending gap. According to Salt Lake City’s Housing & Neighborhood Development Department, building one unit of affordable housing costs roughly $154,000. Providing a home to all 6,800 people currently accessing homeless services would cost the city roughly $1 billion — two-thirds of its entire annual budget.

“We know that it’s cheaper in the long run to provide housing for homeless people, but cities don’t get money back when that happens,” said Tony Sparks, an urban studies professor at San Francisco State University. Expanding social support and building subsidized housing require huge upfront investments that may not pay off for decades. Though the costs of managing a large homeless population mostly fall on hospitals and law enforcement, reducing the burden on those systems won’t put spending back in city coffers.

“If you know how city budgets work, everything goes into a different pot,” Sparks said. “When you save money on health care, it just goes back into the health care system. It doesn’t trickle sideways.”

But all the challenges of funding their response to homelessness doesn’t mean cities are entirely powerless. For a start, municipal leaders could remove the zoning codes that make low-income housing and homeless shelters illegal in their residential neighborhoods. They could replace encampment sweeps and anti-panhandling laws with municipally sanctioned tent cities. They could update their eviction regulations to keep people in the housing they already have.

Cities can also, crucially, address the huge diversity of the homeless population. Rankin points out that for young mothers, the most frequent cause of homelessness is domestic abuse. For young men, it is often a recent discharge from foster care or prison. The young homeless population is disproportionately gay and trans.

All these populations are already interacting with dozens of municipal agencies that haven’t been designed to serve them. Even without major new funding sources, cities could do a lot better with the systems they already have. Schools, for example, could provide social workers for unhoused students. Libraries could invite health care workers to help homeless patrons manage their chronic illnesses. Law enforcement agencies could reorient themselves around outreach and harm reduction rather than arrests and encampment sweeps.

The key, Rankin said, is to make these changes consistent, dynamic and permanent. Like paving roads or running buses, cities will never be “finished” with the goal of preventing and alleviating homelessness. Unless something fundamental changes in the American economy, it is something they will have to do forever.

Back in Salt Lake City, Gregersen is now finishing her college degree and volunteering at the Utah Harm Reduction Coalition. I ask her what she sees as the legacy of Utah’s high-profile approach to homelessness.

“We’re afraid of throwing too much money into this issue,” she said. “We do a little bit here and a little bit there. And then, when it doesn’t solve the whole problem, we say it didn’t work and we try something else.”

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to thisnewworld@huffpost.com.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link