[ad_1]

The first time Andy Warhol met the woman who shot him, he thought she was a cop. Valerie Solanas and Andy Warhol first crossed paths during the Silver Factory days in 1965. She was in her early-thirties and already a well known haunt of Greenwich Village. At that time she was toiling in relative obscurity on her masterworks at the Chelsea Hotel: The SCUM Manifesto, the infamous anarchist-feminist screed, and Up My Ass, an absurdist play that chronicles the exploits of Bongi Perez, a lesbian hustler who describes herself as “so female, I’m subversive.” Solanas had parlayed an invitation to the Factory through an acquaintance, the photographer Nat Finkelstein, with the intention of promoting Up My Ass to Warhol.

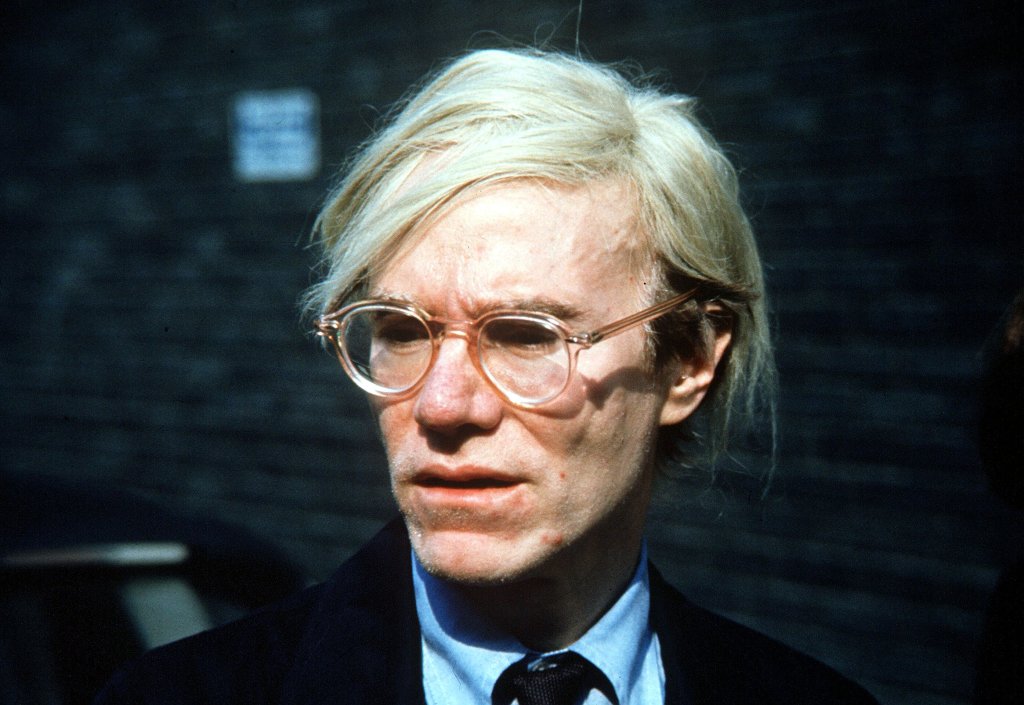

By most accounts, the meeting went well. Warhol thought the title of her play was amusing, and though her serious demeanor and spartan appearance clashed with the Factory aesthetic, she was invited to return. Solanas, for all her vicious ideology, understood that it was sometimes necessary to play the game, and Warhol was a master player. Three years later, she would make her last visit to the Factory with the intention to shoot Warhol to death.

Solanas was an outsider among revolutionaries. While some early feminists had radical leanings, Solanas’s views endorsed a political utopianism more extreme than those of her contemporaries. In 1965, she wrote her “SCUM Manifesto” (its title bore an acronym for Society for Cutting Up Men), which said that men corrupt all human institutions, including “money…Great Art, Culture…” Men, she wrote, “define Great art as themselves.” The only proper form of retribution would be to annihilate all men so as to get away from any form of sexual subservience.

During her brief tenure in Warhol’s orbit she had given him her manuscript for the play, and, whether through her miscommunication or promise, she actually believed he would produce it. She called the Factory frequently to ask about the production; Warhol often recorded their conversations because she was a “great talker.” To her frustration, lines of her dialogue later appeared uncredited in his films.

In one recording she asked him, “Do you envision a place for yourself in the world of the future?” “I thought I was a member of the men’s auxiliary,” he said, to which she replied, “You’re in the men’s auxiliary, but you’re by no means on the escape list…”

Misfits were drawn to Warhol’s Factory, but despite the care they took to appear poor, most came from wealthy backgrounds. Solanas was different in that respect—she was frequently homeless. Her politics, too, put her at odds with Warhol and some of the other Factory denizens. “To place Valerie in the context of the Factory, consider its denizens and the qualities that might have drawn her to this group,” wrote Breanne Fahs in her biography of Solanas. “It offered a stylized facsimile of the world Valerie knew all too well; what she had experienced as hard reality, the Factory appropriated as gritty, artistic drama.”

By fall 1967, her militancy had curdled from amusing to tiresome for the Factory, who soon dropped her. She called its denizens the “stupidstars” and labeled Warhol “a vulture and a thief.” (In return, he described her as a “hot water bottle with tits.”) Shortly afterward, Solanas’s mental health declined. She was tossed out of the Chelsea. She had nowhere to live. She maintained that Warhol had lost the manuscript for Up Your Ass and that he offered to compensate with a part in the film I, a Man. She claimed to have never received payment for her role, though Warhol disagreed. (Here is where Fahs biography and Blake Gopnik’s mammoth biography on Warhol diverge: Fahs claims Warhol cheated Solanas at nearly every turn; Gopnik maintains Warhol’s innocence). A dubious publishing contract with the unscrupulous publisher Maurice Girodias had left production of Solanas’s play in limbo. She started writing hateful letters to Warhol: “I really do believe that if you didn’t have your lies + deception + notarized affidavits, you’d shrivel up + die. Valerie.” She told him that she intended to buy a gun.

By 1968, the Factory had moved from its original location at 241 East 47th Street in Manhattan to a loft on Union Square West. On that sunny afternoon Warhol found her outside the building, waiting, and he later wrote that during the elevator together she was “bouncing slightly on the balls of her feet, twisting a brown paper bag in her hands.” Inside she was met with a small group which included the curator and critic Mario Amaya and Paul Morrissey, Warhol’s executive producer.

Warhol was chatting on the phone when Valerie fired the first shot from her Beretta. Confusion preceded the chaos. Had a bomb gone off at the Communist magazine below? Was it a sniper? Warhol first realized what was happening, and before she fired the second shot he yelled, “Valerie! Don’t do it! No! No!”

Only the third bullet hit him, but it was a true shot, entering under his right armpit and exiting through his right lung. He described the sensation as a “cherry bomb exploding inside me.” Amaya was grazed in the back. And then the elevator doors opened, and Solanas was gone.

At Columbus Hospital, Warhol was declared clinically dead for two minutes. The waiting room filled with veteran Factory members, dressed in their avant-finest, who vied for the swarming reporters. Art dealers Leo Castelli and Ivan Karp made serious statements on Warhol’s legacy. Ex-lovers of the artist wept in the lobby.

Meanwhile, Solanas had approached a young cop in Times Square. “The police are looking for me,” she said. “He had too much control over my life.” For a short while, she was akin to a folk hero among the counter-counter culture, who staged a street performance near MoMA in her honor. High-profile feminists scrambled to distance themselves from her name. Her face appeared on the front page of the New York Daily News, with the headline “Actress Shoots Andy Warhol.” She was charged with the attempted murders of Warhol and Amaya, in addition to possession of a firearm. When pressed on her motive Solanas replied, “I have a lot of very involved reasons. Read my manifesto and it will tell you what I am.”

Critics mined the shooting for meaning anyway—and most chose to lampoon Solanas as a fame-mongerer. Warhol later said “Crazy people had always fascinated me because they were incapable of doing things normally. Usually they would never hurt anybody, they were just disturbed themselves; but how would I ever know again which was which?”

A little over 52 years to the day of the event, Solanas’s attempted shooting stands as a strange incident within the life of one of the most celebrated artists of all time, but if she had been successful in killing Warhol, she could’ve altered art history entirely. And she often said she wished she’d seen the job through. “I consider it immoral that I missed,” she said in a 1977 interview. “I should have done target practice.”

[ad_2]

Source link