[ad_1]

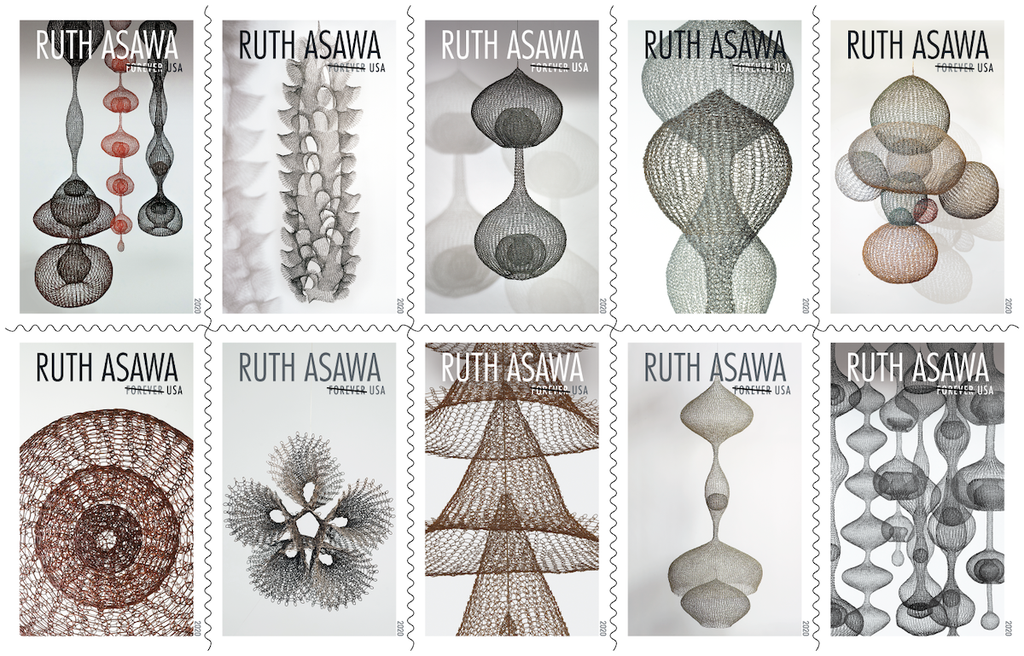

Earlier this month, the United States Post Office issued new stamps featuring artist and educator Ruth Asawa’s airy wire sculptures. Whether because of a new amount of attention being directed at the USPS in light of current events or a revival in interest in Asawa (the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis recently held a major show of her work, and Modern Art Oxford in the U.K. has a forthcoming survey), the stamps have been a hit, both within the art world and beyond. On the occasion of the stamps’ release, ARTnews looked back on the artist’s life and career, from her years at Black Mountain College to some of her public projects and educational initiatives in San Francisco. Below is a guide to major events from Asawa’s childhood and milestones in her practice.

From an early age, Asawa was creating artworks.

Born in 1926 in Norwalk, California, Asawa was the fourth of seven children in her family. Her parents were Umakichi and Haru Asawa, who immigrated to America from Japan and worked as truck farmers. Discriminatory laws prohibited Asawa’s parents from owning land of their own in California or becoming American citizens. Asawa took jobs on farms before and after school, during which she would create sketches and drawings. She once said, “I used to sit on the back of the horse-drawn leveler with my bare feet drawing forms in the sand, which later in life became the bulk of my sculptures.”

© The Estate of Ruth Asawa/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy the Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner/Photo by Hudson Cuneo

Asawa and her family are detained in internment camps in the U.S. during the 1940s.

In 1942, Asawa’s father was arrested and interned in a camp in New Mexico, while she and the rest of her family was detained in Santa Anita, California. The artist and her family would be released from an internment camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, in 1943, when she enrolled in Milwaukee State Teachers College. There, she experienced racism and xenophobia, which ultimately caused her to leave school in 1946 without her degree—the school had refused to place her in a teaching position, which was required to graduate. Asawa subsequently moved to North Carolina to study at Black Mountain College, which was founded in 1933 as a bastion of the avant-garde and had served as a refuge for some artists who fled Nazi Germany and war in Europe.

© The Estate of Ruth Asawa/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy The Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner

The artist developed her practice during her time at Black Mountain College.

Asawa worked closely with her instructors—among them artist Josef Albers (who was the first art teacher to be hired at the institution), designer Buckminster Fuller, dancer Merce Cunningham, and mathematician Max Dehn—at Black Mountain College, and she met architecture student Albert Lanier, whom she would marry in 1949. An early painting by Asawa, Untitled (BMC.95, In and Out), ca. 1946–49, hints at the rhythmic geometry that would come to define her sculptural practice. The work features abstract, arrow-shaped forms that seem to dance across the red canvas in an inexorable, linear choreography.

© The Estate of Ruth Asawa/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy the Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner

Asawa begins showing her work publicly following her move to San Francisco.

Together with Lanier, Asawa moved to San Francisco in 1949, where the couple went on to have six children in the following nine years. It was during this period that the artist started exhibiting her famed hanging wire sculptures at venues including Peridot Gallery in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Oakland Art Museum, and elsewhere. Asawa also presented work at the 1955 Bienal de São Paulo. Of her first sculptural experimentations, which often feature buoyant forms that can cast undulating shadows, the artist once said, “My curiosity was aroused by the idea of giving structural form to the images in my drawings. These forms come from observing plants, the spiral shell of a snail, seeing light through insect wings, watching spiders repair their webs in the early morning, and seeing the sun through the droplets of water suspended from the tips of pine needles while watering my garden.”

© The Estate of Ruth Asawa/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy the Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner

In the 1960s, her sculptures become increasingly intricate.

Inspired by a plant she found in California’s Death Valley, Asawa began creating tied wire sculptures in the 1960s. These works, which now rank among her most famous ones, feature star-shaped centers surrounded by outstretched sinuous branches. In 1965, curator Walter Hopps, formerly of Ferus Gallery fame, organized a solo show of Asawa’s sculptures and drawings at California’s Pasadena Art Museum, which is now known the Norton Simon. It was during this decade that the artist also began taking on public commissions in San Francisco, starting with her sculptures of nursing mermaids in a fountain in the city’s Ghirardelli Square. She joined the San Francisco Arts Commission in 1968 and with architectural historian Sally Woodbridge she cofounded the Alvarado School Art Workshop, which would later become the San Francisco Arts Education Project and worked to bring arts education to schools in San Francisco.

© The Estate of Ruth Asawa/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy the Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner

Asawa focuses on arts education opportunities for students in San Francisco.

In 1982, the artist’s efforts to establish a public high school dedicated to the arts were realized with the opening of the School of the Arts. The audition-based was renamed the Ruth Asawa School of the Arts in 2010, and it now serves as a space where “promising young artists and thinkers collaborate with teachers, professional artists, and their community to explore and develop their personal identity through art, insight, and movements that reflect and influence the world around them,” according to its website.

© The Estate of Ruth Asawa/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy the Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner

In the early millennium, she takes on a large-scale public project and receives a major retrospective.

The last public commission of Asawa’s career was the Garden of Remembrance at San Francisco State University, for which the artist designed a memorial to recognize Japanese Americans interned during World War II, including the 19 SFSU students who were forced to withdraw from the institution in 1942 and detained in internment camps. “I thought it would be nice if we could do something that told the story but not in a bitter way and not just as a Japanese story,” Asawa said of the project, which was unveiled in 2002. “This is a story about liberty and freedom.” Asawa placed 10 boulders symbolizing American internment camps in the garden, and a bronze marker in the space honors the families of SFSU students interned. In 2006, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco presented a retrospective of her work, titled “Contours in the Air” and featuring 54 sculptures and 45 works on paper.

Today, Asawa is one of the most celebrated artists of the 20th-century.

Asawa died in 2013, but her monumental legacy lives on in the art world. Her iconic works can be found in the collections of the Guggenheim Museum and Whitney Museum, both in New York; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the de Young Museum in San Francisco; the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas; and more institutions. The artist’s estate has been represented by David Zwirner, one of the world’s biggest galleries, since 2017, and in 2018 the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis opened “Ruth Asawa: Life’s Work,” the first major museum show of her work in over a 10 years. In 2020, Christie’s sold her 1953–54 sculpture Untitled (S.401, Hanging Seven-Lobed, Continuous Interlocking Form, with Spheres within Two Lobes) for $5.38 million, and David Zwirner presented an exhibition of her work at its London space. Modern Art Oxford in the United Kingdom will open the exhibition “Ruth Asawa: Citizen of the Universe” in January 2021 before it travels to the Stavanger Art Museum in Norway.

[ad_2]

Source link