[ad_1]

The photography of the late Chicana artist Laura Aguilar has caused many to see the world differently. A key figure in the Chicanx and queer art scenes of Los Angeles, she has effectively shaped how we perceive identity today—even if, when she started making photographs, during the 1970s, she wasn’t widely known. With her images focused on her identities as a large-bodied, working-class queer Chicana woman, she considered pressing subjects, like mental health and equity in the art world, that are only today being given their due. “She was so out front with these issues in her work with her body and her identity that people just couldn’t deal with it,” Sybil Venegas, the curator of Aguilar’s recent traveling retrospective and co-executor of her estate, said, adding, “I think the world caught up to Laura.”

Venegas’s retrospective, which debuted in 2017 at the Vincent Price Art Museum in Monterey Park, California, as part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, was a hit. But Aguilar was long overlooked by the mainstream art world, and it wasn’t until the exhibition opened that many learned about her art. “Once the show opened, people were very moved by it,” Pilar Tompkins Rivas, VPAM’s director, said. The exhibition, which made stops at the Frost Art Museum in Miami and the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, is scheduled to open in the fall at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York.

To mark the two-year anniversary of her passing, ARTnews took a look back at the key aspects of Aguilar’s work.

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

Visualizing Identity

Aguilar’s most iconic image is her 1990 triptych Three Eagles Flying, which shows a bare-chested Aguilar in the center panel with a thick rope. With her hands bound and her neck constricted, she appears to be strangled, as if by a noose. Her face is fully covered by a Mexican flag, and she has a United States flag wrapped around her waist. (The two flags appear, hung individually, on either side of her in the other two panels of the work.)

“Three Eagles Flying resists an easy reading,” Charlene Villaseñor Black, a professor at UCLA who teaches Aguilar’s work both in her art history and Chicanx studies courses. “She challenges the idea of the female nude—one of the most important genres in Western art—as the passive object of the male gaze. It’s very clear that she’s aware of the tradition, and she’s able to repeat certain elements from the canon in such a way that shows us how unstable that meaning is and to question these essentialized ideas about women.”

The work visualizes the complexities of identity for people in the Chicanx community, who often feel caught in a space in between their Mexican heritage and their experience living in the United States. “It resonates for many of us who feel bound in-between cultures—who feel silenced,” Villaseñor Black said. “She herself talked about her inability to speak Spanish. She’s not blaming either country. She’s just equally caught between these two.”

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

Working in Community

Some of Aguilar’s other well-known series include several portraits of the communities of which she was a part. She photographed several well-known Chicanx creatives, including artists Barbara Carrasco, Yreina Cervántez, Ricardo and Esperanza Valverde, Harry Gambao Jr., and Diane Gamboa, as well as poet Gil Cuardos.

Her best-known forays into this work, however, are three series she made in succession: “Latina Lesbians” (1986–90), in which she photographs professional Latina lesbians that are annotated with text talking about their identity in their own words; “How Mexican Is Mexican” (1990), which builds on the “Latina Lesbians” series and asks its sitters to describe what it means to be of Mexican descent; and “Plush Pony” (1992), for which Aguilar set up her camera in the Plush Pony bar on L.A.’s Eastside and created studio portraits its patrons, primarily working-class lesbians.

Amelia Jones, a critical studies scholar and art historian at the Roski School of Art and Design at University of Southern California, said her interpretation of these images has changed over the years. “I was originally looking at it as an illustration of a marginalized community, whereas now I look it as a much more complex engagement of a person who was part of that community and these people were here friends.”

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

The Body Politic

Aguilar’s earliest use of her nude body comes in an image made the year before Three Eagles Flying, titled In Sandy’s Room (1989), which shows her sitting in a chair, fully naked, as she tries to cool off in front of a chair, drink in hand.

“She’s doing it on purpose to critique all the ways in which women are confined to certain appearance and look and clothes and body,” Venegas said.

Christopher A. Velasco, her longtime studio manager and co-executor of her estate, added, “She decided to put the camera on herself because she couldn’t communicate like she wanted to with language, so she was like, ‘Let me use the camera on myself and make these self-portraits.’”

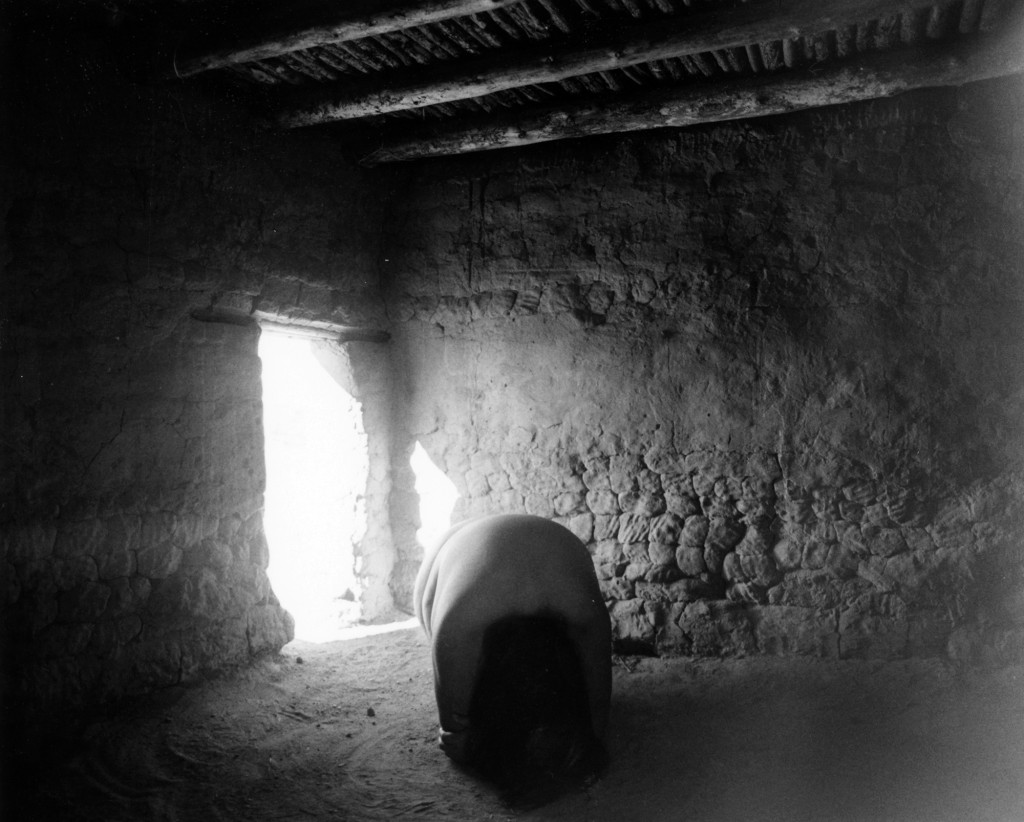

In the years that followed, Aguilar would begin to work more with her nude body, photographing herself from different angles, as she did in Window (Nikki on My Mind), from 1991, as well as in her “Clothed/Unclothed” series (1990–94). She would eventually move into what would become some of her most sublime images where she would place her body in various nude settings, often alone but sometimes with other women. In melding her body with the landscape, Aguilar forced viewers to see her large body, asking them to appreciate its beauty, just as they did with the landscape surrounding her.

“I remember in the ’90s mainstream people dismissing her work and it had to do with the fact that her nude body was so visible,” Villaseñor Black said. “There was this inability to see in her work past their own ideas that this body was inappropriate in artwork.”

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

The Landscape

Aguilar created several series of herself nude in nature beginning the mid-1990s. First came “Nature Self-Portrait” in 1996; then “Stillness” and “Motion,” both in 1999; and “Center” in 2000. All were shot in black and white. She would later use color photography for “Grounded” series in 2006. Each series explores a different approach to dealing with the traditions of landscape photography—a field which art historians have claimed was pioneered by white men. “She’s making these very beautiful modernist compositions, but with bodies that would have never been included in modernist photography,” Jones said.

Aguilar often said that the reason she enjoyed photographing herself in nature, particularly the desert, because “she felt accepted by nature. Feeling the sun on her body was important to her because she did not get a lot of touch in her life. “People didn’t touch her very much physically,” Tompkins Rivas said.

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

Access

Aguilar did not merely accept the ways in which society had sought to marginalize her—she wanted to upend these systems. Some of her most striking series show her fighting for access, not just to the art world but to basic necessities, like having enough money to live and make work. Health care was another frequent focal point.

Among the works in this vein are Will Work for Axcess (1993). Other related works show Aguilar holding cardboard signs saying that she wants access to the gallery system and museums.

“She’s talking about access in so many different from the perspectives of a differently abled person and a Latinx queer artist,” said Rita Gonzalez, the head of contemporary art at LACMA. “All these institutional access that we’re all talking about, so that feels very contemporary now. She found a way of speaking for so many different people.”

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

Mental Health

Aguilar did not shy away from documenting her mental health, and her most emblematic work about her depression, the four-part Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt (1993), shows the artist looking directly at the camera wearing a T-shirt with the words “Art can’t hurt you” on it, followed by an image of her holding a pistol, another of her holding the gun to her mouth, and a final one in which the firearm is about to be fired.

In a text accompanying the work, she describes the pain felt because her work did not achieve recognition and the feeling that she was shut out of the art world for being a queer person of color. “So don’t tell her art can’t hurt,” Aguilar writes. “She knows better. The believing can pull at one’s soul. So much that one wants to give up.”

“Her personal struggles have a universality to them,” Tompkins Rivas said. “They speak broadly to what it means to be human. It’s a journey of self-acceptance. That’s something everybody can relate to.”

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

Humor

In spite of her pictures’ darkness, Aguilar had a sense of humor evident in her final series, “Toy” (ca. 2006), a group of vivid pictures focused on her toy collection. But even the more serious works may contain something funny about them that most viewers don’t get from her nude photographs in nature to In Sandy’s Room and even the “Clothed/Unclothed” series.

Villaseñor Black said, “Thinking about the photographs of the groups of nude women in the landscape, I tend to read those works very seriously as a challenge to the male gaze and canonical representations of the female body in nature, but in some of them there are humorous elements with all the bodies piled up. She has this playfulness that I forget sometimes.”

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

A Perfectionist

Velasco recalled that Aguilar was a perfectionist when it came to her work, and she held herself to a very high standard, often spending hours in the dark room when she still could, before she got sick. She was the rare photographer who often printed her work herself.

Aguilar often was demanding when it came to her work’s technical aspects. Velasco printed some of the photographs for her retrospective and recalled that she would send him back to the dark room several times to work on a print. He would often remind her that some of the chemistry had changed from when she first started printing her work, to which, he called, she would reply, “I understand it’s not going to be the same, but it has to be perfect.”

But there was a reason behind her obsessiveness. “It made me realize that if it didn’t have those qualities people nitpick the work and miss out on what she was really trying to say,” Velasco said.

The Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

How Her Work Is Taught

Aguilar’s work has been a staple in programs devoted to Chicanx studies, queer studies, gender and sexuality studies, and women’s studies. Only rarely has it been considered within the context of art history.

Students in programs other than art history “have said they see Laura as a role model, who despite all her challenges with learning and mental health and body issues, the fact that she speaks about those issues in a manner that is honest, risky, and self-affirming they identify with that and see that as brave,” Alma Lopez, an artist who invited Aguilar into her classes at UCLA, said.

Jones said she has been teaching Aguilar’s work, along with the Chicano art group ASCO since the mid-1990s. “For years and years I was scoffed at by the powers that be in art history and in the art world,” Jones said. “The field was not acknowledging vast swaths of contemporary art. It was about my desire to teach the work of people who had been marginalized by the canon.”

[ad_2]

Source link