[ad_1]

Nicholas Galanin’s White Noise, American Prayer Rug, 2018, is one of two works by the artist included in the 2019 Whitney Biennial.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

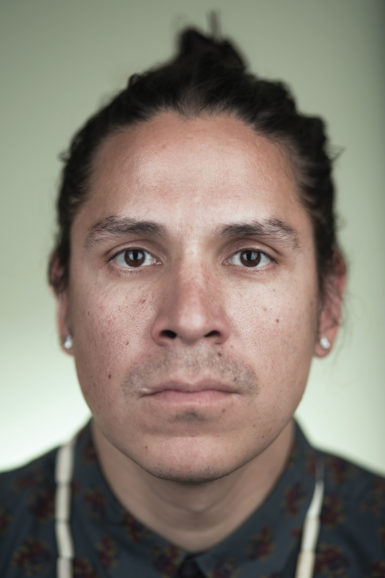

Nicholas Galanin is an artist and citizen of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska. He is of Tlingit and Unangax̂ descent, and lives and works with his family in Sitka.

In July I was one of eight artists who requested that our work be pulled from the 2019 Whitney Biennial in protest of the presence on the Whitney Museum board of Warren B. Kanders, owner of the company Safariland, a manufacturer of tear-gas canisters and other weapons used against protesters around the world. I was also part of the same group of artists who, when Kanders resigned a little more than a week later, chose to remain in the exhibition. For me, the reason for both decisions was to fight erasure.

Nicholas Galanin.

©CARLOS CRUZ

My position as an Indigenous artist invited to show at the Biennial had been conflicted from the start. I accepted the invitation fully aware of Kanders’s position on the board and the potential for both conflict and—I hoped—conversation about culture and capital, in relation to Kanders as well as other issues that transcend him. The Whitney, like so many other institutions of its kind, has historically continued the long American tradition of erasure by way of a lack of Indigenous artists represented in exhibitions and collections. In the past, when it has been acknowledged at all, Indigenous art has too often been romanticized, fetishized, and homogenized through a Eurocentric lens, all in the service of lies about who we have been, who we are, and who we can be.

As an Indigenous artist, I am not new to the feeling of being seen as spectacle. Indigenous cultures have been objectified in World’s Fairs and in display cases, our ancestors’ bones secured in museum storage even as our populations shrank through forced starvation and removal. While museums claim to be safe spaces for sharing knowledge and generating discussion, this has not been true from my Indigenous perspective.

But in order to have agency in such spaces, you have to show up. It’s more impactful to engage in conversation than to avoid it. That is not the same for everybody, but for me it is important and true—and showing up in the interest of engagement was part of the promise of exhibiting at the Whitney.

I agreed to contribute to the Biennial because underrepresented voices are so rarely given such a platform from which to tell their truth. The invitation presented me with acknowledgment of my work but, more important, with a responsibility to my culture, my community, and my ancestry.

Prior to the group request with other artists to have our work pulled, we—along with additional artists in the show and important figures from around the art world—sent a letter to the Whitney asking the museum to remove Kanders from the board. For me, it was about more than just tear gas. Tear gas is a means of biological warfare designed to clear space. Today, it is used at Standing Rock in North Dakota, at the border between the U.S. and Mexico, in city streets. Kanders and the war profiteers who supply tear gas and other weapons have no place guiding our cultural institutions. And those institutions do not have to accept direction from such sources or reward them with board positions or namesake galleries.

[See a complete timeline of the Kanders controversy.]

But the Whitney, like so many other museums, continues to draw on toxic philanthropy that wields power over our communities while creating a self-congratulatory climate of comfort for the existence of economic disparity, cultural suppression, erased histories, and white guilt. This is all part of the noise that White Noise, American Prayer Rug (2018), one of my two works in the Whitney Biennial, refers to: distraction from economic, cultural, and environmental realities constantly being generated to justify and protect the status quo.

Nicholas Galanin’s Let them enter dancing and showing their faces: Shaman, 2019, is installed on a ground-floor window at the Whitney Museum in New York.

We live in a nation built on white supremacy, and white supremacy fuels the militarization of our borders and the lands between them, for Indigenous people as well as others of different descent. It has been as American as apple pie for white officers of the law to attack black and brown men, women, and children since the era of “Manifest Destiny.” When such communities assemble in protest, it is very possible they will be removed—cleared from the space they’re in—by a Safariland-manufactured canister. Our children are being taken from their parents, innocent people killed in the streets, our families and communities torn apart. If you are able to view such conditions from a position of comfort and can’t see why I and other artists might remove work in protest, then this is an opportunity to look and listen, carefully.

The media coverage of protests at the Whitney Biennial, starting with actions organized by the activist group Decolonize This Place before the show opened and continuing through mass letters sent to the museum and the ultimate call for artwork to be taken back, has largely focused on making protest into spectacle rather than listening to different perspectives and valuing them for what they are—thoughtful calls for action.

My decision to remove my work from the Whitney came when my hope for meaningful conversation was met with inaction—on the part of many but, most fatefully, by the museum, which for weeks and then months failed to issue any meaningful response to protests mounting within its walls. For me, that inaction translated to complicity with militarized denial of the right of Indigenous people to freely move through land that we belong to.

I am glad that Kanders left the board. I’m glad that the exhibition curated by Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta—which reflects the strengths and values of creative people of color, women, LGBTQ, and other artistic voices who came together to insist we do better in our institutions—remains intact and on view for the duration of the Biennial through September 22.

The protests had everything to do with the Whitney Museum and its capacity to contribute to culture. Culture not only reflects the reality of life and politics—it creates it. My aim is to engage in conversation based on reality—to create change rooted in responsibility and resist cultural amnesia that would have us mistake the status quo as acceptable or just.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of ARTnews, on newsstands September 24, under the title “Standing Together.”

[ad_2]

Source link