[ad_1]

Tanisha Gordon doesn’t see what white people love so much about cottage cheese. Or salads, especially when they’re topped with fussy ingredients like candied almonds, pickled carrots or Brussels slaw.

Gordon is a 37-year-old employee at an IT company in the Washington, D.C. area, and until recently, her diet was deeply saturated with fast food ― McDonald’s, Taco Bell, you name it. When her doctor diagnosed her last year with pre-diabetes and prescribed her a CPAP machine to help her sleep through the night, she began working with a nutritionist to clean up her diet. But the lifestyle change she sought would require more than cutting out Chicken McNuggets.

As a black woman, Gordon battled the perception that most of today’s healthy food is “white people food.”

“A lot of the time, when you go to restaurants now, they have these extravagant salads with all these different ingredients in it, like little walnuts and pickled onions ― like the stuff Panera sells,” Gordon told HuffPost. “For me personally, that’s like a white person’s food. A lot of the mainstream stuff that’s advertised comes across as being for white people.”

Today’s Goop-lacquered definition of healthy eating has made it de rigueur to guzzle $9 bottles of cold-pressed kale juice or chug hydrogen-infused water. In this micro-bubble of fastidiousness, a healthy diet means more than consuming your daily dose of fruits and veggies. It means eating pudding made of chia seeds (yes, the same ones used to make Chia Pets) and sprinkling your açai bowl with goji berries, even if you have no idea what either of those things are.

There’s nothing wrong with being nutritionally ambitious, but we’ve cultivated a health food culture that’s unattainable for the multitudes who can neither afford nor identify with it.

“You’ve got the dominant culture in the USA being white culture,” black restaurateur Dr. Baruch Ben-Yehudah told HuffPost. “And that white culture has taken the power to define all things good as white, and all things white as good. So that definition of healthy eating is not an accurate depiction of eating healthy.”

Over the course of a year, Gordon shed 60 pounds and outgrew the need for a CPAP machine simply by making some changes to her diet. But food isn’t always the biggest obstacle to a healthy lifestyle. Cultural barriers can be just as powerful.

White culture has taken the power to define all things good as white, and all things white as good. So that definition of healthy eating is not an accurate depiction of eating healthy.

Restaurateur Dr. Baruch Ben-Yehudah

“For a person who needs to re-train their mind and think differently about healthy eating, that’s always gonna be their struggle; getting past, ‘This plate of food is for a white person,’” Gordon said.

Healthy food has historically been less accessible to black Americans in a number of ways. So, does eating healthy have to be equated with eating like white people? According to a new generation of chefs, nutritionists, academics and patients, the answer is no.

Charmaine Jones, a Washington D.C.-based dietician who is black, penned a short paper earlier this year called “Do I Have To Eat Like White People?” that shared the dietary struggles of her clients, whom she describes as primarily low-income African-Americans on D.C. Medicaid.

The majority of her clients seek nutrition strategies to treat obesity, Type 2 diabetes, heart disease or high cholesterol, a set of challenges that are particularly prevalent in the black community. Gordon was one of her clients.

Jones describes “white people food” as salads, fruits, yogurts, cottage cheeses and lean meats ― the standard low-fat, heart-healthy foods promoted by the U.S. Dietary Guidelines.

Every five years, a 14-member advisory board writes those guidelines, which dictate what the average American should eat to maintain a healthy lifestyle. The current board has only two black members. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services didn’t respond to HuffPost’s request for comment.

Isabella Carapella/HuffPost

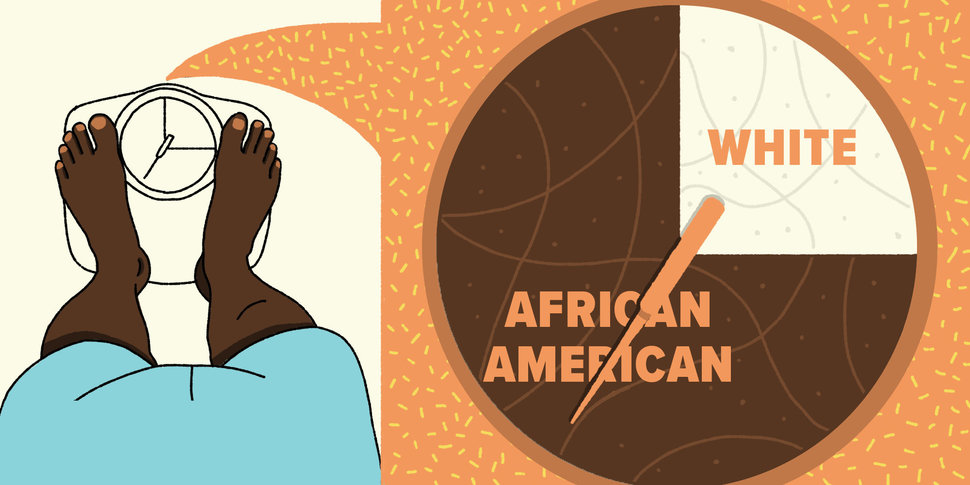

African-Americans are at a much higher risk for a number of genetic predispositions and health issues, many of which are strongly influenced by diet. The numbers speak volumes.

-

Black Americans face a significantly higher risk of diabetes than white Americans, particularly for Type 2 diabetes: The prevalence is 1.4-fold to 2.3-fold higher in African-Americans.

-

The prevalence of high blood pressure in African-Americans in the United States is among the highest in the world. That high blood pressure is often attributed to higher rates of obesity and diabetes in the black community, as well as a gene that potentially makes African-Americans more salt sensitive.

-

African-American adults are nearly 1.5 times as likely to be obese as white adults. While approximately 32.6 percent of whites are obese, the rate for African-Americans stands at 47.8 percent.

Jones’ clients say they didn’t find it easy to get help in the black community.

“I found it difficult to find a black nutritionist. [Jones] was the only one I found when I was looking,” Gordon said. “Part of the reason I picked [Jones] was because she had similarities to me. I felt as if she would understand my body type more and she would understand the culture I come from more.”

“Even after I met her, I asked her what made her become a nutritionist, and she said, growing up, she’d never seen a black person be a nutritionist. So that was something we definitely related on and ultimately why I picked her.”

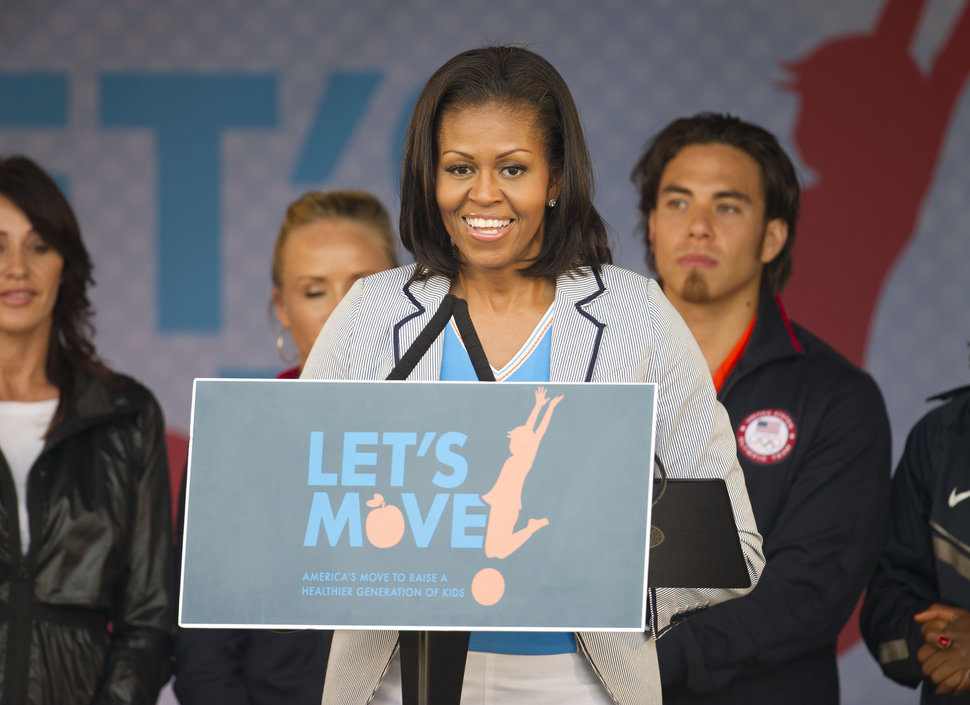

That’s not to say the black community isn’t without its proponents for healthy eating. Former first lady Michelle Obama launched the “Let’s Move” campaign in 2010 to address the problem that one-third of U.S. children are overweight or obese. She sought to break down cultural and socioeconomic divides by cultivating partnerships with big business and championing sweeping legal changes that would affect both the rich and poor.

But Obama often met resistance, finding that food is an everyday comfort that many Americans aren’t willing to compromise on.

Empics Entertainment

Jones says she runs into this problem with many of her clients.

“It’s very frustrating,” she told HuffPost. “My clients feel pressure that they have to change the way they eat. They have to start incorporating foods that are not common to them. So any time that happens, there’s a resistance against the pressure.”

Natalie Webb, another registered dietician and nutritionist in the D.C. area who is also black, told HuffPost that her clients share that same frustration.

“My clients absolutely associate healthy eating with eating like white folk,” Webb said. “I think it stems from what people see in marketing and what they associate healthful eating with, and it often doesn’t include foods they’re familiar with.”

“When you change folks’ food ― especially people of color ― it’s like you’re asking them to change who they are,” Webb said. “That’s why it’s so important as a dietician to start where folks are and introduce foods that are going to be familiar but maybe in a little different way.”

Psyche Williams-Forson, associate professor and chair of American Studies at the University of Maryland, powerfully described how people react to interventions in their diet.

“When you go into a person’s culture and you say, ‘You can’t eat this,’ or ‘You can’t do that,’ it’s just like going into your house and moving your furniture. You’re going to feel violated, you’re going to feel invaded. It makes people feel like their cultural sustainability has been compromised.”

“I try to encourage people to remember that food is part of the constellation of material objects that we deal with every day. And every time you have a material possession that’s been taken away from you, you’re going to be very protective.”

When you go into a person’s culture and you say, ‘You can’t eat this,’ or ‘You can’t do that,’ it’s just like going into your house and moving your furniture. You’re going to feel violated, you’re going to feel invaded.

Psyche Williams-Forson, University of Maryland

Few, if any, cuisines are more firmly attached to African-American culture than soul food, which took on an especially political meaning in the 1960s.

Williams-Forson explained that when writer Amiri Baraka coined the term soul food in the ’60s, he was very specifically responding to a criticism that the African-American community didn’t have its own culture. “Baraka chronicled a number of foods that at the time were heavily eaten by people in the South, everything from ham to sweet potato pie and sweet tea,” she said. “The actual label of soul food became a political term.”

Cultural historian Jessica B. Harris has echoed that argument, writing that in the 1960s, “soul food was as much an affirmation as a diet. Eating neckbones and chitterlings, turnip greens and fried chicken became a political statement for many.”

“In short, soul food was more about blackness than it was about a specific list of ingredients,” author Adrian Miller wrote for the website First We Feast.

Ben-Yehudah adds even more context: “Soul food is an experience in culture, it’s an experience in connecting with not only the people around you today, but connecting with the souls and the spirits of those that came before us that had created an identity for the food we were consuming,” he told HuffPost. “It not only provided nourishment but also allowed us to have a good experience. The soul food was a comfort food. It comforted us in times of difficulty.”

Isabella Carapella/HuffPost

Erica Bright is a 45-year-old management analyst who sought Jones’ help last year to make some dietary changes. She’s been making positive changes to her health by adjusting what she eats, something she was open-minded to since the beginning of the process. But she doesn’t think everyone feels that way.

“The thing that bothers me about eating healthy is that in the media, people appropriate different ways of eating to different people,” Bright told HuffPost. “And so I don’t necessarily feel like black people eat as unhealthily as people would assume that we do. If you think about Italian food, which I love, it’s just as fatty [as soul food], but it doesn’t have that same reputation.”

She points out that the origins of Southern food took root at a time when it was necessary to cook with less-than-ideal ingredients.

“Some people think all black people eat is chicken and collard greens, and that’s not necessarily true. However, out of utility and necessity, we ate a lot of that down South back in the day because that’s all that was available. It’s not like we didn’t know what carrots or Brussels sprouts were.”

“Stereotyping is extremely frustrating. We all have to find an approach to food that still respects and honors our culture. We can still respect our ancestors for how they had to eat out of utility. Now, I have a lot more choices than they did. I shop at Whole Foods, I can go to Trader Joe’s.”

It’s especially evident that these diet stereotypes don’t always apply when talking to someone like Novella Bridges.

Bridges is a 45-year-old nuclear chemist who lives in the D.C. area. She started seeing Jones in 2017 to treat high blood pressure that suddenly arose after both of her parents passed away. Unlike many of Jones’ clients, Bridge pays out of pocket for the nutritionist’s services. But more significantly, she has been eating healthfully her whole life.

“I was raised by a nurse,” Bridges told HuffPost. “I didn’t have to make a lot of changes once I started seeing [Jones]. I was used to eating the food pyramid, so I was raised in such a way that we all were real big on fruits and vegetables. Most people from the inner city or from my culture didn’t eat a lot of those vegetables, but we did.”

Bridges sees herself as being from a distinctly different cultural cross-section than most of Jones’ clients, and she doesn’t feel closely connected to her roots through the foods she eats.

Some people think all black people eat is chicken and collard greens, and that’s not necessarily true. It’s not like we didn’t know what carrots or Brussels sprouts were.

Erica Bright, 45-year-old management analyst

“I would never qualify what I eat as being from one culture or the other,” Bridges said. “No matter who you are, you need to eat fruits and vegetables every day. The bottom line is, we’ve gone to a processed way of eating, and African-Americans have claimed that as their type of food. [African-Americans] want to dismiss healthy eating as being for white people because it’d require a change. The truth is, when people are asked to change, change is difficult.”

“It has more to do with class than race,” she added.

Indeed, money is an inevitable issue when it comes to healthy eating.

Larry Perkins is a 40-year-old married father of two and a Walmart employee. His doctor sent him to Jones last year because he had been diagnosed as pre-diabetic. He made the suggested dietary changes with aplomb, but not without increased financial strain as he attempted to provide healthy meals to his family.

“The most frustrating thing about being on a diet is not having the money to purchase the stuff that you need,” Perkins told HuffPost. “It’s hard to pay for it.”

“A lot of the healthier meals are not marketed toward us. When you go to Sweetgreen or Chopt, their menu is not geared toward low-income families. I can’t take my family there to eat healthy without breaking the bank.”

“I think it’s more of a class issue than a race issue, because in all actuality, you’ve got low-income people, black and white, trying to eat healthy, and the prices really aren’t geared toward any of us,” Perkins said. “We all want to eat healthy, but they just don’t market their menu for us.”

Jones, too, cites socioeconomic factors as one of the primary roadblocks preventing her clients from transitioning to a healthier diet, in part because her clients do the majority of their shopping in food deserts, which lack access to affordable, healthy foods like fresh fruits and vegetables. In the United States, many low-income black neighborhoods can be considered food deserts.

Based on the United States Census Bureau’s Income and Poverty in the United States report from 2016, the average black household made $39,490, while the average white household made $61,858. While only 11 percent of white Americans lived below the poverty level, 22 percent of the black American population did.

There are, however, those who warn against using the term “food desert” as a blanket assessment of a community. Forson-Williams explains: “Every community has a means of sustaining itself culinarily. Not every community may have a supermarket, but supermarkets are not panaceas.”

Jones has to find innovative ways to help her clients make healthy choices when the options are sparse. “Most of my clients live in economically disadvantaged areas, and I have to become creative and learn what’s in those stores to direct my clients how to eat healthy from those places.”

Though Jones teaches her clients how to make healthier soul food at home, finding healthy restaurants that serve soul food is another issue entirely. HuffPost talked to two black restaurateurs who run vegan soul food restaurants, chef Gregory Brown and Ben-Yehudah, about their experiences.

Barbara Haddock Taylor/The Baltimore Sun/TNS via Getty Images

Brown is co-owner of Land of Kush, a vegan soul food restaurant that opened in downtown Baltimore in January 2011. His restaurant specializes in dishes like vegan BBQ rib tips, smoked collard greens, vegan mac and cheese, candied yams, vegan drumsticks, smoothies and fresh-pressed juices. He created his restaurant to provide patrons with a healthier version of soul food, which he says is inherently unhealthy. “It’s heavy, greasy, animal-product based … in its original form, it was really just scraps. Not the healthiest things. Black people just kind of made it taste good to make it palatable. That just became the cultural regularity.”

Ben-Yehudah is the owner of several restaurants, including vegan soul food restaurant Everlasting Life in the Capital Heights neighborhood of D.C. He agrees that soul food has been in need of a healthy makeover.

“Soul food is always greasier, it’s always saltier, and it’s always sweeter,” Ben-Yehudah said. “So those three elements that we don’t need more of in our diet are definitely found it more abundance in today’s soul food diet. I call it the Standard Black American diet, and it has created many of the health challenges that we have today because it’s void of nutrition, it’s full of toxins and it’s addictive.”

But now Brown sees a change in pop culture that’s influencing the black community to make some healthy changes.

“Just in the past three years or so, you just see an influx of popularity of veganism in pop culture. You see celebrities and athletes eating a plant-based diet. You hear about [NBA player] Kyrie Irving, Beyoncé and Jay-Z, you hear about a lot of different celebrities going vegan, so it makes people more willing to try it if they hear about their favorite celebrities doing it.”

But when Brown first opened his vegan soul food restaurant seven years ago, he saw some resistance from the black community.

“There’s always resistance,” Brown said, “because people are stuck with their culture, their background, their traditions. It’s a part of their living. It’s difficult to break people away from that, so people show a little resistance.”

African-Americans might say, ‘I don’t want to eat like white people.’ However, at the end of the day, it’s not eating like white people, it’s actually eating the way we used to eat before we were brought to this country.

Restaurateur Dr. Baruch Ben-Yehudah

Brown’s solution to changing customers’ mindsets is meeting them where they are and finding a path toward healthy eating that lies somewhere in the middle.

“That’s the basis of our restaurant: Meet people where they are,” Brown said. “Black people like barbecue and they like collard greens, they like yams. Let’s offer that to them but at the same time, let’s put quinoa on the menu, and let’s also have some fresh fruit smoothies. That’s how we integrate it into people’s mindset. What do you like to eat? Let me tell you how I can make that vegan.”

“What we want to provide is the full transition,” Ben-Yehudah echoed. “We want to meet the person who’s accustomed to the fried fast food, meet them there and be able to provide them a transition point so they can engage the vegan, healthier food lifestyle.”

And that healthier food lifestyle doesn’t have to look white.

“African-Americans might say, ‘I don’t want to eat like white people,’ said Ben-Yehuda. “However, at the end of the day, it’s not eating like white people, it’s actually eating the way we used to eat before we were brought to this country.”

“I don’t think there’s such a thing as white people food,” Williams-Forson said. “But I think there are foods that have been assigned to black people, and there are foods that have been more in line with white communities. And I think soul food is largely what gets short-handed as black people food, and things like veganism and vegetarianism get short-handed as white people food. Quite frankly, African-American people have been eating white people’s food since we arrived on this continent. But a lot of folks don’t know that because the food we tend to get associated with is almost always soul food.”

And though redefining one’s diet always comes with challenges, for Bright, the journey to a healthier lifestyle turned out to be much more personal than cultural.

“We can learn how to make the foods that we love in a [healthier] way and be comfortable with that. It’s not an insult to Grandma and Mommy and how they used to make these things,” said Bright, whose mother died of colon cancer and whose grandmother had heart issues.

“I want to honor them by learning how to do this whole thing a little bit better. A different diet could have maybe kept them here a little while longer. It’s important to me: I feel like if I can learn how to do this a little better, I’m still honoring them, and I think they’d be proud of me in the process. I think that’s the kind of shift we have to make collectively.”

[ad_2]

Source link