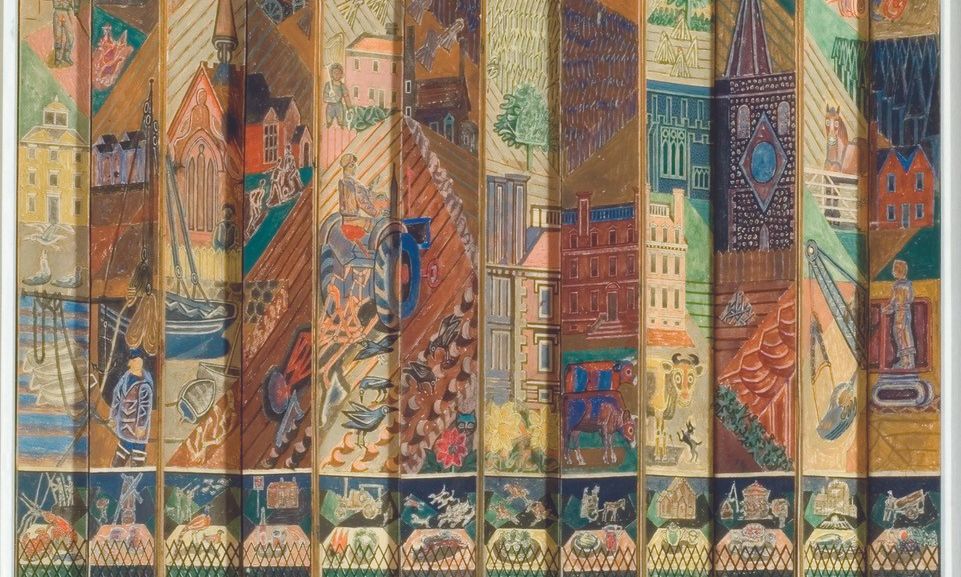

Pubs and churches, country houses and cottages, horses and hounds, gardeners and miners, and rural people at work and play, crowd Edward Bawden’s much smaller watercolour version of his Country Life mural for the 1951 Festival of Britain

Courtesy of Higgins Bedford

The hunt is on for a monumental painted wall screen by Edward Bawden (1903-89), displayed at the Festival of Britain in 1951 and then lost by the government a decade or so later. The artist’s executor, the retired art dealer Peyton Skipwith, describes the multipanel painting, titled Country Life, as “among the most important British art works of the post-war years”.

Bawden’s Country Life was entrusted to the government after the festival came to an end, but in 1961 a Treasury official dealing with its future was scathing: “Its decorative value is a matter of opinion, and it is not considered saleable for any other purpose, or even as firewood.”

Jacob Rothschild’s Waddesdon Manor, owned by the National Trust, would like to track down Country Life, since it has recently acquired a major John Piper mural that was also displayed at the Festival of Britain, along with two other important Bawden murals. Pippa Shirley, director of Waddesdon, finds it “extraordinary that Country Life, this high-water mark of Bawden’s career, would have been so undervalued that it was allowed to vanish into thin air”. She adds: “I can’t help hoping that it must still survive, somewhere.”

Fortunately, we have a very good idea of what Bawden’s festival Country Life mural looked like, thanks to a detailed watercolour study that is now in the collection of the Higgins museum in Bedford. The huge mural itself was painted on 72 plywood sheets and arranged in a free-standing concertina screen measuring 47 feet high and 36 feet wide.

Country Life was commissioned for the festival’s Lion and Unicorn Pavilion on London’s South Bank (close to where the Hayward Gallery was later built). The pavilion set out to reflect “British character and tradition”, and the Bawden covered its entire back wall as part of the Eccentricity and Humour section.

The upper portion of Country Life’s vertical panels are painted with images of pubs and churches, country houses and cottages, horses and hounds, gardeners and miners, and rural people at work and play. Near the bottom of the panels runs a series of still lifes of country produce.

The pavilion was controversially demolished soon after the festival ended. It is said that Churchill’s incoming Conservative government did so because the festival was so closely associated with the previous Labour government. The Festival of Britain was designed to be a national celebration of successful recovery from the Second World War’s devastation. It was centred around a five-month expo on London’s South Bank, with an important arts element.

The then recently established Arts Council selected Country Life as one of the festival works of art that ought to be preserved in public ownership. Its panels were disassembled and stored by the Ministry of Works at its Barry Road premises in London.

What happened next has been partially reconstructed by archivist Ann Chow, based on declassified government papers at the National Archives. These papers note that “long storage has caused deterioration”, not surprisingly since the Ministry of Works was hardly the most appropriate institution to store art works. Its Barry Road warehouse was due for demolition in 1961.

The file also records that the Treasury then agreed the Bawden should be offered to the Berkshire Institute of Agriculture, in the village of Burchetts Green, provided it would pay the £3 carriage fee. Last month The Art Newspaper contacted what is now the Berkshire College of Agriculture, which said it knew nothing about the panels (at 47 feet tall, they would have been difficult to miss).

It is possible that Country Life never went to the agricultural college at all. Bawden once wrote that the work “fell into the hands of a demolition contractor, who sold it to a dance hall”, adding that “the Arts Council have bought it back but are uncertain what to do with it”. An Arts Council spokesperson told us it is not in their collection. Tragically, the Bawden may simply have been bulldozed in the Ministry of Works store. Any readers with information about the fate of Country Life should contact Waddesdon Manor’s director.

Meanwhile the Rothschild Foundation has bought two other Bawden murals, both of which were commissioned in the late 1940s for the first-class lounges of two Orient Line ships which sailed between the UK and Australia. They were ordered by Colin Anderson, an Orient Line director, a collector of Modern art and a former Tate Gallery chairman.

The liner Orcades had Bawden’s English Garden Delights (1948) and the Oronsay had The English Pub (1951), both redolent of traditional British life just after the war. Each is nearly 18 feet wide, and painted on 11 panels.

The liners were scrapped in the 1970s, a victim of competition from air travel, and the works of art were removed and sold. In 1990 The English Pub was acquired by the now retired London dealer Peter Nahum. He sold it at Christie’s in 2006 for £36,000. It was later bought by the dealer Liss Llewellyn, from whom the Rothschild Foundation recently purchased it. Separately, the Rothschild family had earlier acquired English Garden Delights through a different route.

Following its acquisition of John Piper’s The Englishman’s Home, another major mural commissioned for the 1951 Festival of Britain, the Rothschild Foundation also wants to track down Bawden’s Country Life

© John Piper Estate, Courtesy of Liss Llewellyn

In addition, the Rothschild Foundation has recently bought the monumental John Piper mural The Englishman’s Home (1951). This had also been commissioned for the Festival of Britain, for the Homes and Gardens pavilion, where it was displayed on the exterior. Painted on 42 panels, The Englishman’s Home is 51 feet long and 16 feet high. Among the buildings it depicts are Brighton’s Regency Square, the dome of Castle Howard, near York, and the Epsom villa of the artist’s mother.

The Piper, too, has had a chequered history. After the festival it was donated to Harlow, one of the post-war new towns, and later displayed at Harlow Technical College until 1992, when the building was demolished. It too was later purchased by the Rothschild Foundation from Llewellyn.

Shirley hopes to be able to display the two Bawden liner panels and part of the Piper in a special exhibition at Waddesdon Manor, possibly next year. In the meantime, three of the Piper panels and the pair of Bawdens are on show in Waddesdon’s Stables café.

Discussions are under way to lend The Englishman’s Home for temporary display at the Museum of London, when it reopens on its new site at Smithfield in 2026. Few venues have the space to show this Festival of Britain survivor in its full glory.