[ad_1]

Finnigan Jones spent last spring and summer in the Texas Capitol fighting anti-transgender bathroom legislation. But the attacks on the state’s LGBTQ community just kept on coming.

He decided to run for the state House of Representatives. “I can’t sit back and watch this anymore,” he said.

A catalog compiled by Logan Casey, a research associate at Harvard, shows Jones is one of an estimated 36 openly transgender candidates (so far) running for various levels of government across the U.S. this year. In what is perhaps a twist on political gender disparity, openly trans men make up just a small fraction of them.

Of the 36 candidates tracked by Casey, only six are trans men. These figures form part of a larger picture, in which trans men are largely absent from politics. A report from the LGBTQ Representation and Rights Research Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which looked at 126 trans and gender variant people running from 1977 to 2015, found that trans men accounted for fewer than 10 percent of openly transgender candidates and elected officials.

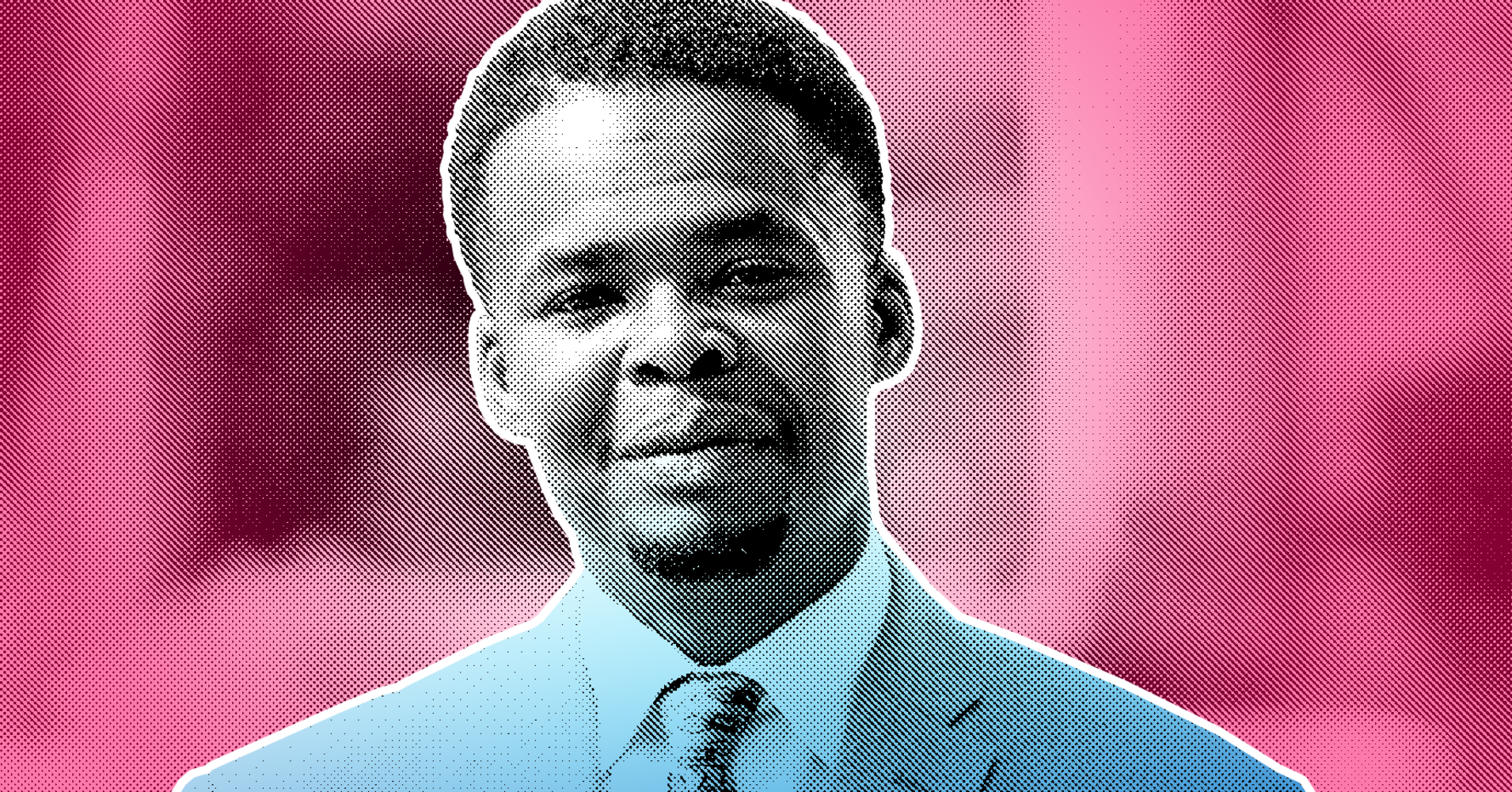

“A lot of people don’t even know we exist,” said La Don Henry, an African-American trans man running for the Nevada Assembly. “That’s another reason why I wanted to take this opportunity, to put a face to transgender men.”

On the night of Donald Trump’s election as president, Henry said, his wife woke him up crying, telling him it was “OK to hide.” But Henry, a retired veteran, wanted to stand up for his rights and his community.

Last year the transgender community celebrated a historic number of victories, including the election of Danica Roem to Virginia’s House of Delegates. She was one of 10 trans people to win a seat in government in 2017. Many believe that this, coupled with state attacks on trans rights — which, according to the National Center for Transgender Equality, have seen an uptick since Trump’s election — is behind the record number of trans people seeking office in 2018. Less is understood, however, about why so few trans men are putting their names on the ballot.

Andrew Reynolds, the director of the LGBTQ Representation and Rights Research Initiative, who co-authored the report with Casey, said there wasn’t enough research to determine why this disparity exists, but there are shared theories.

He said trans men often report finding it easier to blend in with cisgender people. That includes Henry, who believes transitioning from female to male is easier than male to female because testosterone helps with the development of physical features associated with masculinity, such as facial hair and a deeper voice.

Reynolds said this suggests there may be trans men in office who don’t publicly identify themselves as trans. He said trans men who aren’t visibly transgender may find it easier to bypass abuse and vilification.

“That means that they may be slightly less engaged because they’re not at the very hard line of discrimination,” he added.

Dylan Forbis, who lost his primary race for the Texas House in March, said his experience during his transition serves as an example of that. A former plumber’s apprentice, he was fired when he began transitioning about six years ago. He said that although he challenged the decision and lost, he didn’t have to deal with the ridicule or violence that trans women regularly face.

“While I worked [as a plumber’s apprentice], I saw these men that I worked with make fun of trans women while I was transitioning,” said Forbis.

Trans women, particularly trans women of color, are overwhelmingly on the front line of discrimination and violence. So far this year, at least 12 transgender people have been killed in the U.S., and at least 28 transgender deaths resulted from violence in 2017. The majority of those killed were trans women.

“I think what we’re seeing is direct action of a stone being thrown into their waters, versus a pebble being thrown into mine,” Forbis added.

Several trans men who spoke to HuffPost, including Casey and Jones, said they believe that being socialized and perceived as female before their transition could play a role in holding back trans men from pursuing careers in politics.

Jones, who won his primary unopposed in March, believes this is especially true in the conservative South, where women are often discouraged from seeking leadership roles. He said it took “a lot of guts” for him to step up and run for office “because you’ve got to get out of that mindset.”

The cumulative consequences of underrepresentation in government largely center on social repercussions, many of the trans men who spoke to HuffPost said. However, some believe there are also links between political representation and gaps in health care for trans men.

Tyler Titus, who became the first openly transgender person elected to office in Pennsylvania when he won a seat on the Erie City School Board last year, said an absence of trans men in the public eye fuels damaging ideas about them.

“When we are not seen or don’t have a spot at the table, it paints a picture that we don’t really exist or that we’re a smaller amount of the population than what we really are or that we’re somehow an anomaly,” he said. “That further feeds into this ignorance or this fear that this is a choice of some sort.”

Politics aside, Titus said, it’s vital for trans children to see someone like them in leadership roles. “I was desperate for somebody like me to be out in the front, to see that I wasn’t broken,” he said. “It’s so important for those kids to know that they are not broken.”

Disparity in health care

Reynolds suggested that underrepresentation of trans men in public office can translate to other areas, such as health care. Research on transgender health care is limited, but the studies out there tend to focus on trans women. He said trans men and women have unique health care needs, “so having a trans woman at the table doesn’t necessarily guarantee you that you’re actually going to get a good feel for trans male issues.”

Jones, who is a consultant for Parkland Hospital in Dallas and sits on the advisory board for the Diversity Center of Oklahoma, said one such area where trans men have specific needs is gynecology. He said many doctors haven’t been trained to work with trans men, which can have a major bearing on whether they return for future care.

Jones added that for trans men, visiting the gynecologist can be a traumatic experience.

“I would feel uncomfortable in a gynecology office sitting in a waiting room as a man, with no women sitting or no wife sitting next to me,” he explained. “That alone causes trans men to never see a doctor for those problems because of the shame, because they’re embarrassed, because of the dysphoria. They don’t even want to admit that they have female parts, sometimes.”

In 2016, Jones assisted Parkland Hospital in developing a gender clinic, which now has a gynecology clinic specifically for trans men. “I took all the girly stuff out of the waiting room,” he said. “I said no using terms like ‘menstrual cycle’ — anything that is female related. Say ‘blood’ or change it to something else, because that helps with their mental stability.”

Underrepresentation of trans men hurts trans women too

Casey said that underrepresentation in politics is hurting not just trans men and that trans women end up suffering too. Nowhere is this playing out more obviously than in nationwide debates about transgender rights to bathroom access. Casey said that when people — especially opponents — talk about trans people and their right to access facilities that correspond with their gender identity, they’re almost exclusively talking about trans women.

“They’re talking about men parading as women, going into bathrooms to do whatever. And it’s almost as if trans men don’t exist in this equation,” Casey said, adding that this exclusion generates a “sort of specter stereotype” that’s damaging to trans women and has a disproportionate impact on increasing the likelihood of discrimination and violence against them.

“The fewer trans people there are, whether running for office or in office, the more that each one of those people has to bear the burden of representation and to speak for everybody,” he said.

On the rise

Although the number of trans men currently running for office is low, Casey said that number is rising. If in the past 40 years, trans men made up only about 4 percent of trans candidates, Casey’s catalog shows that today that number is about 15 percent. Furthermore, according to Elliot Imse, the communications director at the Victory Fund, an organization dedicated to electing openly LGBTQ people, more trans candidates are expected to announce races this cycle. This means more trans men could appear on the ballot this year.

For Forbis, losing the March primary isn’t the end of the race.

He has since been offered a job working for Democratic congressional candidate Sri Preston Kulkarni. Forbis plans to use the skills and experience he is gaining when he runs for office again in 2020.

He believes getting more trans people on party payrolls is key to boosting the number of trans men in politics.

“Hire trans people,” Forbis said. “We want to run for politics. We want to do this stuff, but sometimes we’re in circumstances that we can’t do that on our own bill.”

#TheFutureIsQueer is HuffPost’s monthlong celebration of queerness, not just as an identity but as action in the world. Find all of our Pride Month coverage here.

[ad_2]

Source link