[ad_1]

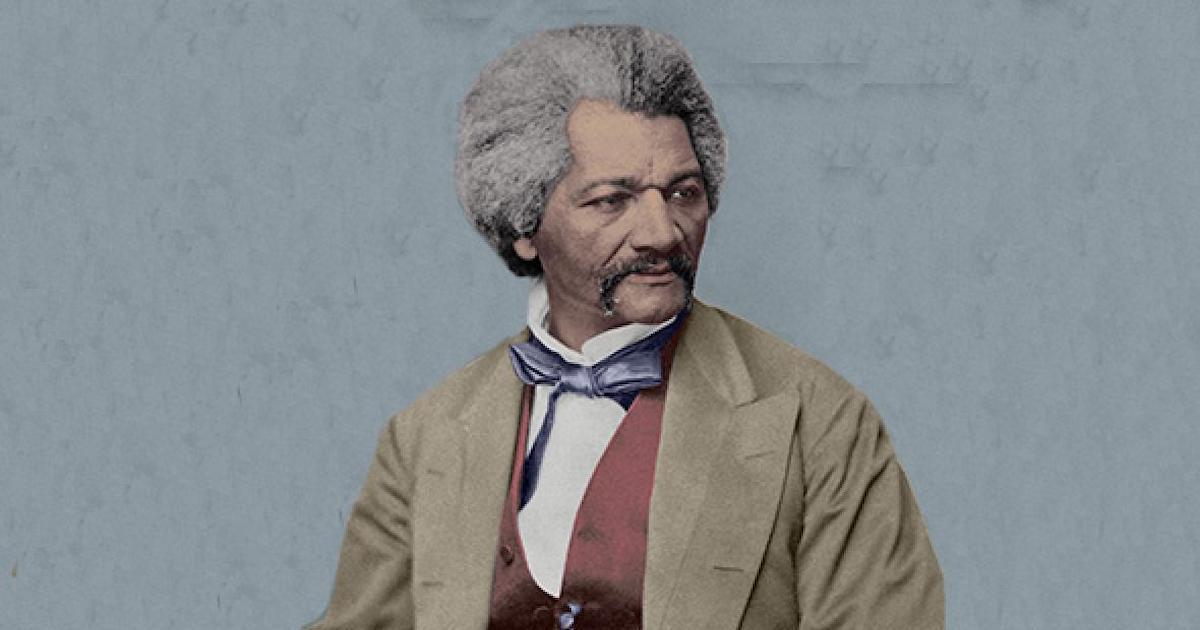

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?” Famed black abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass posed this question before a large, mostly white crowd in Rochester, New York on July 5, 1852. It is “a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim,” Douglass explained, adding that he felt much the same: “I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! … This Fourth [of] July is yours not mine.”

A little over a decade later, however, African Americans like Douglass began making the glorious anniversary their own. After the end of the Civil War in 1865, the nation’s four million newly emancipated citizens transformed Independence Day into a celebration of black freedom. The Fourth became an almost exclusively African American holiday in the states of the former Confederacy—until white Southerners, after violently reasserting their dominance of the region, snuffed these black commemorations out.

Before the Civil War, white Americans from every corner of the country had annually marked the Fourth with feasts, parades, and copious quantities of alcohol. A European visitor observed that it was “almost the only holy-day kept in America.” Black Americans demonstrated considerably less enthusiasm. And those who did observe the holiday preferred—like Douglass—to do so on July 5 to better accentuate the difference between the high promises of the Fourth and the low realities of life for African Americans, while also avoiding confrontations with drunken white revelers.

[ad_2]

Source link