[ad_1]

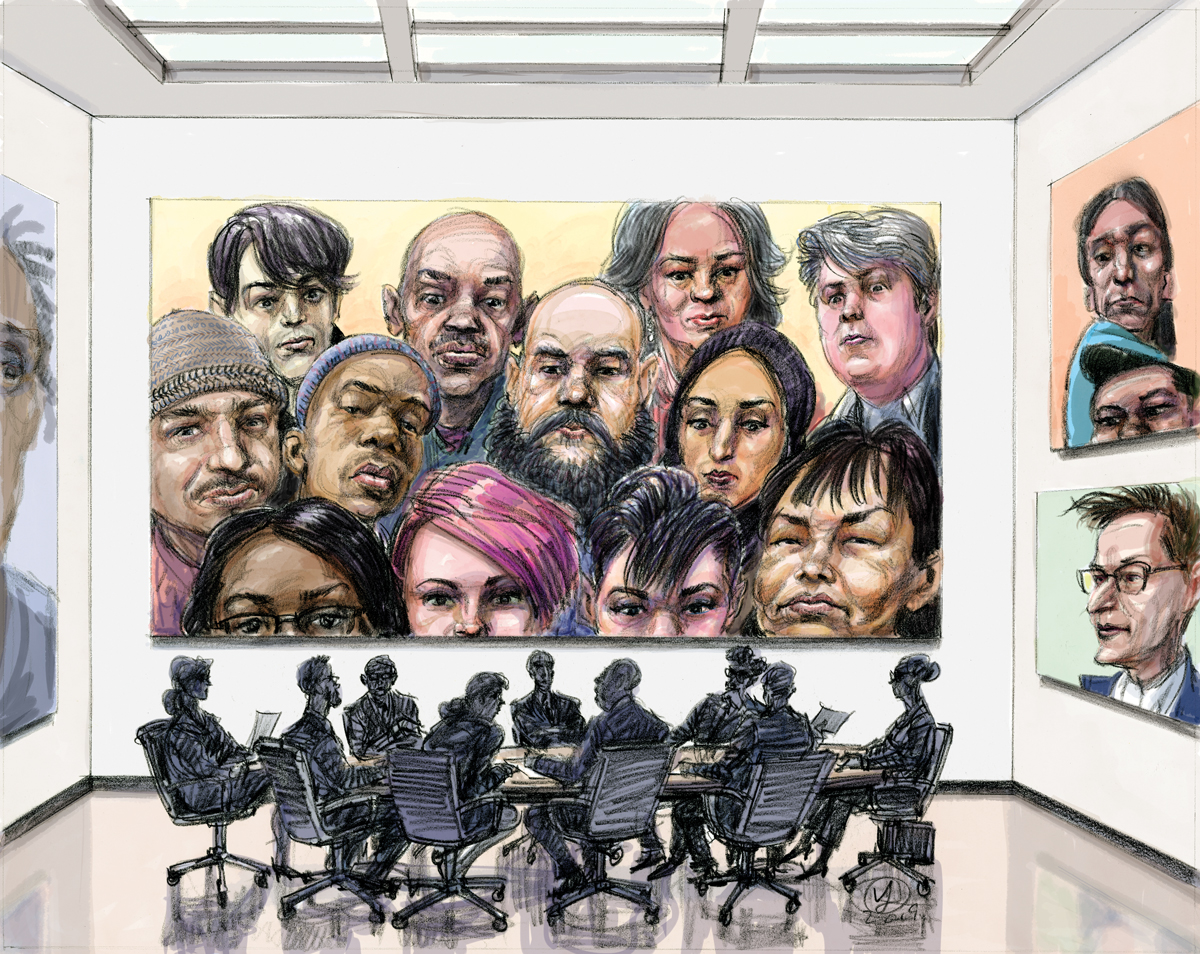

A museum board under scrutiny.

ILLUSTRATION: VICTOR JUHASZ

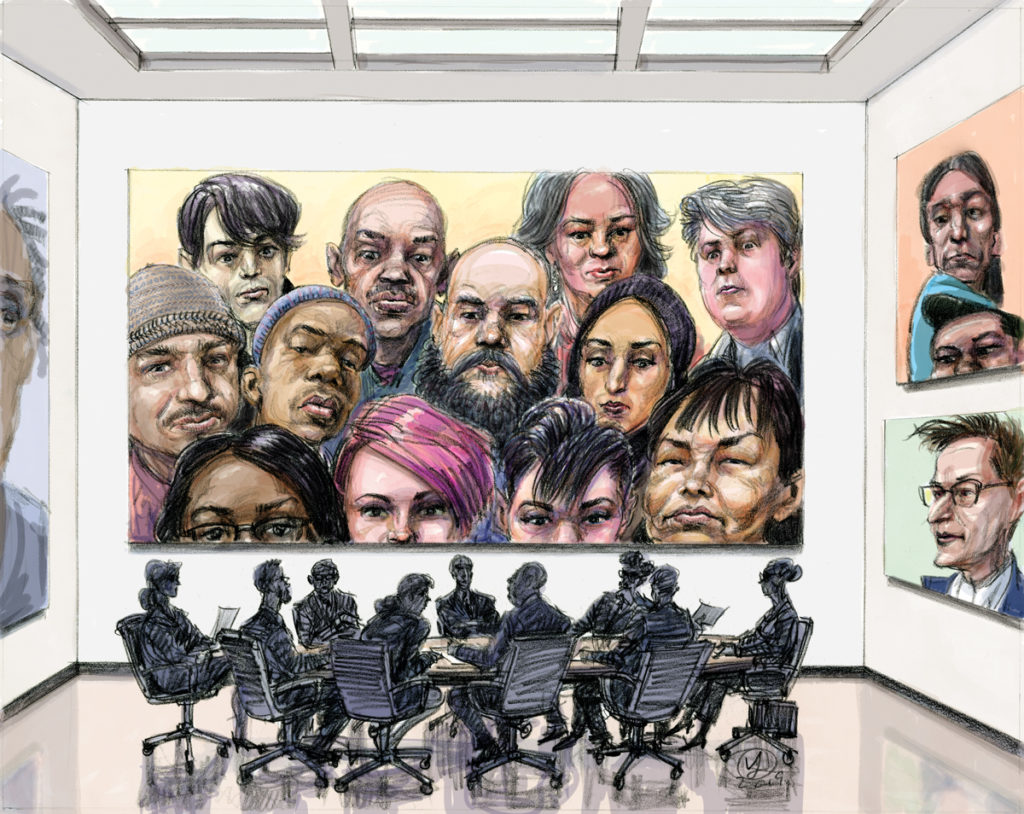

On a cold night this past February, a group of students, artists, and activists filled the rotunda of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Some released clouds of flyers styled after doctors’ prescription pads, carrying the slogan “Shame on Sackler,” a reference to the philanthropic family whose name has become synonymous with the opioid crisis. Others lay on the floor, staging a “die-in.” The action was the latest in a series led by famed photographer Nan Goldin; as information has become public through a series of lawsuits that the Sackler family’s company, Purdue Pharma, widely and successfully promoted OxyContin despite knowledge of its addictive effects and its role in some 200,000 deaths from overdose, Goldin, through her organization, PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), has pressured museums both in the U.S. and Europe to relinquish ties to the family. Her efforts have not been in vain: By April, the Guggenheim—which houses the Sackler Center for Arts Education and received $9 million from the Sackler family between 1995 and 2015—announced that they would no longer seek or accept donations from this source.

“My god, museums are the repository of culture; they’re supposed to be a safe place in this world that isn’t dirty where you can actually enjoy beauty and learning,” says Goldin, who started PAIN a year and half ago as she herself was recovering from an addiction to OxyContin. “The Guggenheim has made a strong declaration and I hope that other American museums will follow suit. I don’t know what they are waiting for.”

Once ivory towers of culture, far removed from politics and controversy, museums have increasingly come into the spotlight as sites of protest and places where equity, diversity, and inclusion have become imperatives. From the push of the New Museum’s staff for unionization to the Museum of Modern Art’s plans to reinstall its permanent collection to reflect a diversified canon, museums across the country are now more than ever under pressure to change, both for practical and ethical reasons. Museum directors, ever aware of the need to address changing demographics and the demands of social media–savvy audiences, are adapting to this evolution, though for many, this is a sharp departure from their traditional training in art history and curatorial studies.

Nan Goldin protesting the Sackler family.

ILLUSTRATION: VICTOR JUHASZ

The Guggenheim wasn’t the first institution to respond to Goldin’s protests, which began at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018 and have since been held at the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Freer|Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. Days before the Guggenheim made its announcement, the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Modern, both in London, made similar statements, and mere days after all these announcements were made, the Sackler Trust, a London-based philanthropic organization, said it would “temporarily pause” donations to arts institutions. Last week, as ARTnews went to press, the Met, whose Sackler wing houses the Temple of Dendur, announced that it, too, will cease accepting Sackler money. The Smithsonian with its Freer|Sackler Gallery is reviewing its donation policies. This is a victory for PAIN far beyond their expectations and a clear indication that museums are increasingly sensitive to political pressure and public perception of their fund-raising practices.

In New York, PAIN’s wasn’t the only protest going on. Downtown, the Whitney Museum of American Art was under siege for nine weeks leading up to the Whitney Biennial, with weekly demonstrations led by a coalition of groups under the umbrella Decolonize This Place. The organization takes its name from one of an exhibition that prompted its creation in 2016. The founders protested the funding by a pro-Israel organization of “This Place,” a show at the Brooklyn Museum that dealt with the Israel-Palestine border. At the Whitney, DTP is focused on the removal of vice chairman Warren B. Kanders from the Whitney board. Kanders’s company, Safariland, manufactures teargas canisters and other products that have been used against asylum seekers along the U.S.-Mexico border. In December, 95 Whitney staff members, including curators Marcela Guerrero and Rujeko Hockley, signed an open letter that urged the museum to consider asking for Kanders’s resignation. Whitney director Adam Weinberg responded by calling for conversation, and Kanders issued a statement saying that he was “not the problem.” In April, a letter signed by more than 100 critics, curators, and academicians, including Benjamin Buchloh and Hal Foster, urged the Whitney to take action. A few weeks after the letter was first released, nearly 50 participants in the 2019 Whitney Biennial added their names.

Though Weinberg, through a Whitney representative, declined to be interviewed for this article, it is clear that Decolonize This Place is having an impact and that its wide-ranging goals are not limited to the Whitney. For DTP, “decolonizing” covers six areas—a free Palestine, indigenous struggle, black liberation, patriarchy, degentrification, and global wage workers—according to Marz Saffore, an artist and key organizer of the collective. “There’s different things you can pick out from any institution and what’s great about using museums in this way is that it offers a platform for multiple struggles to come together because many of the people that we all can point to as a common enemy are art-washing their money, gained through real estate or . . . through state violence,” she said.

Museum directors, ever under pressure to raise funds to sustain their institutions, are on notice now, perhaps more than ever before. Whereas public protests in the 1990s came mostly from the right over controversial artworks in what was called the “culture wars,” the new wave of protests is more concerned with social justice issues and is harder to dismiss. Fund-raising demands have been extreme for directors for nearly two decades, during a time of expansion for institutions, but, said Bruce Altshuler, director of the Program in Museum Studies at New York University, “I don’t think that’s really changed the nature of the job.” The new issues are another story. “More recently, social media and the way in which museums are increasingly in the public eye around especially ethical issues has become very fraught and makes the job extremely difficult,” Altshuler said. “And has happened very quickly.”

A protest held by Decolonize This Place held at the Whitney Museum on March 22, 2019. Speaking here is Alicia Boyd, of the group Movement to Protect the People.

KATHERINE MCMAHON/ARTNEWS

You could say that the times of museum unrest began in 2017, with the controversy over Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, Open Casket (2016), whose showing at the Whitney Biennial that year was met with now-famous demands that the exhibition’s curators remove and destroy it, due to the image’s capitalizing on the pain of black Americans. (The work by Schutz, who is white, remained intact and on view for the show’s full run.) Or you could say it began before that, at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, where a fall 2016 exhibition of paintings by Georgia-born artist Kelley Walker triggered a public boycott. Walker, who is white, employed appropriated images of African-Americans, and smeared them with chocolate and toothpaste, angering a group of protesters who called for the exhibition to be removed. The museum responded with a town hall discussion and shortly thereafter, the show’s curator left the institution.

“I really believe that a museum becoming a site of protest is something that in some ways should happen,” CAM’s director, Lisa Melandri, said recently. For her, increased sensitivity on the part of museums is a positive development. “That moment of protest is a place where you gain an acute awareness that something is affecting people seriously deeply and . . . protest is the way they manifest that criticism. It’s a moment for us inside the institution to gain that awareness and to listen.” As a result of the controversy, practices at CAM have changed. The full staff, including education and public relations, are brought in early in the discussions about potential shows at the museum, as is the board. Melandri says that this is not a new policy so much as a change in practice, doing what they have already done but with increased sensitivity. “We are really digging into by whom and for whom is the art. We’re much more involved in longer conversations about how the work will function in the public sphere and to whom will it give voice. The process can sometimes be painful but I don’t think that makes it bad.”

Another museum that has been on the receiving end of public backlash is the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis, where Sam Durant’s outdoor sculpture, Scaffold (2012), was criticized by the Native American community in 2017. A public work examining America’s history of the death penalty and public executions, Scaffold incorporated a scale replica of a historic gallows upon which 38 men—all from the Dakota tribe native to the area that is now Minnesota—were executed by hanging in 1862. What was intended as an interactive installation sparked protests that eventually led to the artist’s working with the Dakota community to dismantle the piece, and Dakota tribal elders buried it.

“The whole Scaffold controversy was traumatic and sad in terms of this institution’s history, but it also created an environment where people [came to] understand the level [at] which this has to be engaged,” said Mary Ceruti, who became director of the Walker this past January. The Walker has responded to criticism from the Native American community by initiating a new commission by a Native American artist for the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden; they also launched an annual film program of Native American directors. This past February, museum staffers joined local activists at a march in Minneapolis for missing and murdered indigenous women. “You can’t give lip service to diversity or treat it as a P.R. or marketing conversation,” said Ceruti. “It has to be internalized by the institution; because Scaffold was such a visible and large-scale episode, it required that the institution look really hard and engage in the hard conversations, so there has been support from the board and the staff for doing the right thing, thinking differently and changing the lens we are looking through.”

Arguably, it is such controversies that have led some museums to react preemptively. Late this past April, the Art Institute of Chicago postponed the exhibition “Worlds Within: Mimbres Pottery of the Ancient Southwest,” slated to open May 26, for lack of an indigenous-aligned scholar or curator to accompany it. Originally, the exhibition was to be curated by Brian Just of the Princeton University Art Museum, a partner on the project. But after holding a “scholar’s day” in December, convening experts from the Native American community, Just withdrew over concerns that indigenous viewpoints were not represented, leaving the show without a curator. “We are trying to be guided by best practices and [to] evolve best practices in a leadership role where we can,” said James Rondeau, AIC director, adding that the museum is actively looking for the appropriate curator to provide scholarship for material that served chiefly funereal purposes. “We look at everything through the lens of an inclusion dialogue. As you know, museums around the world have been a target of a new kind of scrutiny, some of it very fair, some of it not so fair, but we are very mindful of evolving best practices in light of that heightened scrutiny.”

While some museums have been forced into this conversation through public outcry, many more are anticipating the changing demographics of their audience and increased audience sensitivities, and are incorporating this into their programming. Change is occurring in museums across the U.S. and while progress is slow, museums are gradually diversifying their boards, their staff, and their collections, often in order to address their local communities’ interests and needs.

“I’m very proud of the fact that at the McNay, access to beauty is not a privilege, it’s a right to every member of our community and that’s what informs all of our work,” said Richard Aste, who became director at the San Antonio institution in 2016. Aste, who will tell you that the McNay, founded in 1929, was once known as a kind of country club, has initiated a series of innovations, including making the museum completely bilingual and hosting its first exhibition of African-American art. Recently, the McNay exhibited “Estampas Chicanas,” prints by Mexican-American women artists of the 1980s and ’90s, and this summer, it will launch “Transamerica/n: Gender, Identity, Appearance Today,” a controversial show especially for south Texas, for which the museum is preparing the public beforehand with a series of speaking and listening engagements because, as Aste put it, “nobody likes surprises.”

“When I was called to apply for this job, the words in the museum’s mission statement that really spoke to me were ‘to engage a diverse community,’ ” said Aste, who interpreted that to mean “engage everyone.” He noted that San Antonio is 64 percent Hispanic and “our board agrees that our strength comes from our diversity and they want to reflect that in the museum’s mission to connect everyone to the McNay experience.” Aste, who himself is an immigrant from Peru, has also made changes to diversify the staff and elevated the education department to senior leadership positions in order to make audience participation a more significant part of museum programming. “We’ll know we have a success when the inside of our campus matches the outside of our campus,” he said.

The McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas.

COURTESY THE MCNAY

Christopher Bedford, director of the Baltimore Museum of Art since 2016, has been making such an effort for a few years now. “Baltimore is a black majority city with an institution that has not been as attentive to that population as it might have been, so I was interested in constructing a black majority museum for a black majority city,” Bedford said. He made waves in spring of 2018 when he sold a Rauschenberg, a Warhol, a Kline, and works by two other artists to raise $16.1 million to put toward diversifying his institution’s collection. “Given the minority majority nature of Baltimore and given my conviction that the most important art being made today is by black artists, and finally, given that there is an undiscovered history of 20th-century art that could be made to predominate in an encyclopedic context, I felt a deep draw to this institution and this city to pursue those passions.”

Bedford is determined to bring the lens of equity and inclusion to every aspect of the museum, including the collection, the exhibitions, the public programs, the staff, and the board. He is already initiating such innovations as a museum satellite program in a public market in a predominantly African-American neighborhood near the museum and a partnership with Greenmount West Community Center, started by artist Mark Bradford, where the museum provides support for the physical space and for nonprofit status, as well as a printing press on which artists in residence make work that is sold in the museum shop and whose proceeds are sent back to the community. Bedford also scores as an important victory the appointment, in September 2018, of Asma Naeem as chief curator, made possible by a $3.5 million grant from a local couple. “To me, her appointment and the specific means of endowment was really meaningful.”

Bedford sees these changes as no more radical than the museum’s history of accepting the Cone sisters’ collection of modern masters at a time when Matisse’s reputation was still controversial. “We have a history of risk taking and we have a history of excellence, and I think the risk is substantially lower today when there is broad consensus that Julie Mehretu, Mark Bradford, and Theaster Gates are living treasures than it took for the BMA to accept the Cones’ collection. I don’t think it has to do with political correctness. It has to do with our very core, which is excellence and relevance.”

For Christine Anagnos, who for eight years has been executive director of the Association of Art Museum Directors, these changes at museums are coming partly as a result of a new generation of directors. “This new generation of museum directors [is] learning and adjusting to lead very different museums than the ones that they grew up with,” she said. “Inclusion requires knowledge and skills and abilities that are not necessarily taught to museum professionals in their typical training tracts, and you shouldn’t expect anyone to learn through osmosis.”

One member of that new generation is Amada Cruz, who has been director of the Phoenix Museum of Art for the past four and a half years. Cruz believes that “the entire infrastructure of the museum has to change if you really want to reflect the community that you are working in.” She received some pushback from a few long-standing docents earlier this year, when she converted the museum to a bilingual institution and put out a welcome sign saying Bienvenidos, addressing the large Hispanic community in Phoenix. But according to the director, the press coverage of a couple of disgruntled people should not overshadow the success she has had bringing in new audiences to the museum, boasting up to 7,000 people for the opening of a Kehinde Wiley exhibition.

“The role of museum director has changed very dramatically,” Cruz said. “My generation thinks about audience very intensely.” She contrasts her approach with “the old model of museum as temple and you open the doors and let people in, but you do not do a whole lot about it.” Acutely aware that she faces stiff competition for an audience’s attention, and not just from other cultural institutions, she insists, “we have to work harder and we have to meet the audience halfway. I know it sounds like a cliché but I think that’s actually true.”

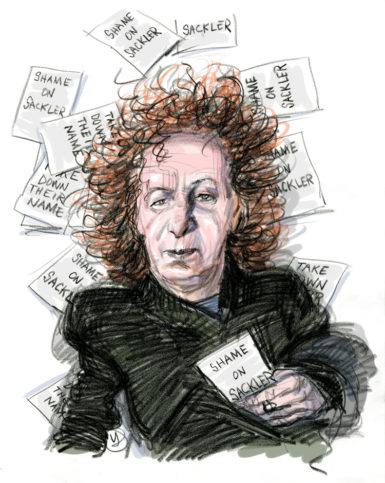

Jill Snyder, director of MOCA Cleveland.

ILLUSTRATION: VICTOR JUHASZ

That isn’t to say that museum directors who have spent decades at their institutions aren’t doing crucial work. Jill Snyder, who has been director of Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland since 1996, decided there was no better way to demonstrate inclusion than to hold an Open House, complete with town crier, a spoken-word ensemble, and a live DJ. In April the museum celebrated its 50th anniversary by throwing open its doors and announcing that from now on it will be admission-free for all visitors. In preparation for first-time museum visitors sure to be lured by this invitation, the museum changed its entire program of audience interaction, including the issuance of new “engagement guides” for museum staff and replacing traditional docents with paid part-time educators, chosen from underrepresented communities, who will have access to mentors and training. Even its choice of an opening show, “You Are Not a Stranger,” was an interactive performance by artist Lee Mingwei emphasizing acts of kindness between strangers.

“Contemporary artists engage in some of the most urgent and relevant issues that reflect our world, and we want this museum to be a gathering place for diverse people to engage in those issues,” said Snyder. For her, going free wasn’t enough: to address the legacy of museums as places of exclusion, a whole roster of change has to take place to make a museum seem more welcoming. “Art challenges us to examine things from multiple perspectives and we certainly don’t believe there’s only one way to view art, and that encourages a healthy discourse and dialogue that reinforces a civility.”

A wake-up call for museums came four years ago, when Ithaka S&R, an independent research firm, collaborated with the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Association of Art Museum Directors, and the American Alliance of Museums to field a questionnaire on diversity to museums across the U.S. The dismal results found that museum attendees were about ten percentage points more racially and ethnically homogeneous than the U.S. population, and that curators, educators, conservators, and museum leadership were 84 percent white non-Hispanic, four percent African-American, six percent Asian, three percent Hispanic, and three percent two or more races. This past January, they published a follow-up report that showed demonstrable gains in education and curatorial positions, though museum directors remain 88 percent white. The Mellon Foundation has funded an undergraduate curatorial fellowship program where students of color and others dedicated to making museums more open and inclusive are exposed to curatorial and other museum functions. These undergraduate fellows are then encouraged to pursue graduate education in preparation for potential art museum careers. Mellon has also strengthened its investment in the curatorial program at the historically black women’s university Spelman College, and has embarked on an initiative with the Ford Foundation, the Walton Foundation, and the American Alliance of Museums to work toward increasing board diversity.

“I think it was Arnold Lehman who said the most important book a museum director should be reading is the census,” said Anagnos of the former Brooklyn Museum director. “He was very early on in recognizing the changing demographics of this country and how that will play out in visitorship and what audiences are looking for.” Insisting that diversity, equity, and inclusion are now key factors in museum administration, Anagnos said it goes beyond hiring to encompass board development, exhibition programming, education, and outreach.

Tom Finkelpearl, Commissioner of New York City Department

of Cultural Affairs.

ILLUSTRATION: VICTOR JUHASZ

While protesters from PAIN and DTP address different issues, New York has perhaps not surprisingly been an early adopter on the diversity front, given its demographics. “This has been something we have been on since the very beginning of the de Blasio administration,” said Commissioner Tom Finkelpearl of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, who engaged Ithaka to conduct a study of New York cultural institutions of all sizes, published in January 2016. The results showed that two out of three people working in cultural institutions are white, whereas two out of three people living in New York City are people of color. Worse yet, the survey of 35,000 jobs in the cultural sector showed that the single whitest category was curators and that maintenance and security staff remained predominantly African-American.

As a public agency funded by taxpayer dollars, the Department of Cultural Affairs took the situation seriously and has initiated a series of programs to remedy the imbalance. First, it initiated the CUNY Cultural Corps fellows that has allowed 340 CUNY undergraduates to get paid internships in the cultural sector, ranging from small local organizations to Carnegie Hall. But more important, the DCA now ties funding to development of diversity, equity, and inclusion plans, creating economic incentives to initiate such programs. “Have you ever been to a cultural institution where you saw the staff was truly diverse that didn’t also have diverse programming and diverse audiences?” Finkelpearl asked rhetorically, answering, “in my experience, diversity of staff is key to diverse audiences and diversity of programming.”

Finkelpearl said he keeps front-of-mind a metaphor provided by Sharifa Hampton, a diversity consultant at the College of Staten Island. “Diversity is being invited to the party, inclusion is being asked to dance, and equity is getting to decide what music will be playing,” he said. “It’s not good enough to just get people into the room. You are talking about a diverse group of folks who actually get to be DJs.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 38 under the title “Exhibiting Change.”

[ad_2]

Source link