[ad_1]

This is a time of recollection and hope for Jews as well, with Passover. In biblical times, those who were able to make the journey traveled from far-flung parts to Jerusalem to celebrate the liberation of Israelites from captivity in Egypt. This captivity was, then as now, as much emotional or spiritual as physical. Jesus and his followers were among those Jews who made their way to Jerusalem.

As Easter approaches in a time of global anxiety and, often, despair, I find myself trying to remember things I’ve been told that have mattered. As a Christian, I pray, meditate, and read the scriptures — the Bible, of course, and my favorite poets as well. I’m 72, with “underlying conditions.” A lot of water has passed over this particular dam. But one memory in particular comes rushing into my head.

About 50 years ago, I was in a bleak mood. A graduate student at the time, I was doing some research at Oxford, and had gone up to London to a library for the day. Walking back to the train station in late afternoon, on a crowded street, I felt overwhelmed. My hands grew sweaty, and I couldn’t breathe. For respite, I found a quiet passageway where I sat in a doorway for an hour, quite certain I would die.

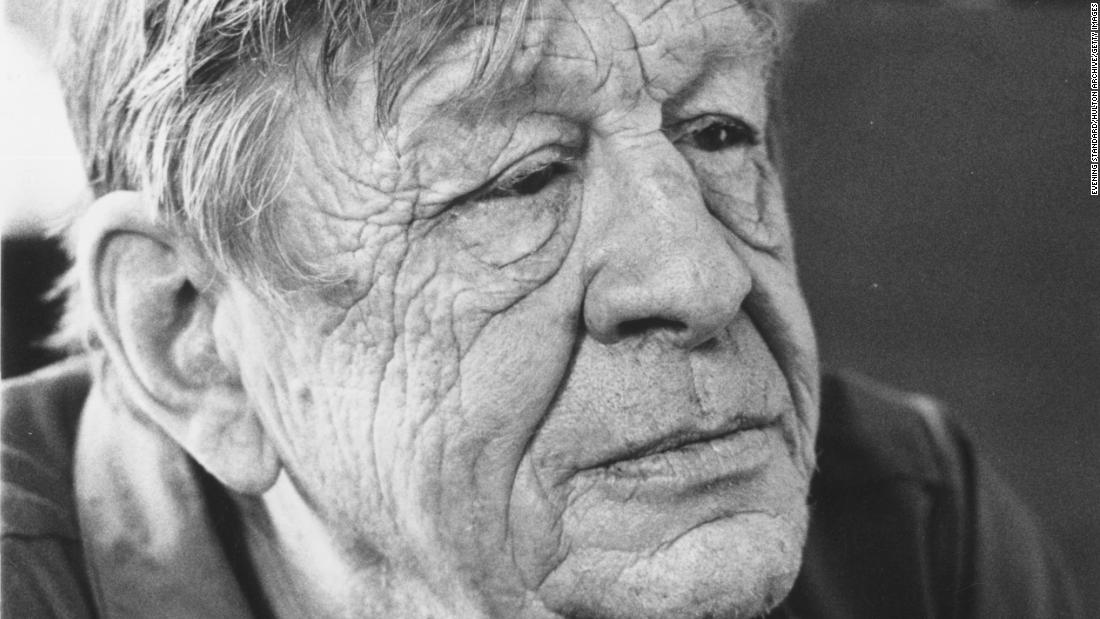

I slowly made my way back to Oxford by train. Heading into the college gate, I ran into the old poet W. H. Auden, whom I had known a little. He was living at Christ Church in a cottage in a garden behind the Senior Common Room. Auden saw I looked glum and said, “Whatever is the matter, dear boy?”

I told him I felt gravely ill, and he said, “What you need is a stiff drink.”

He led me to his ramshackle cottage and sat me down on a sofa that smelled of rotten sandwiches and damp newspapers, bringing me what looked like a cereal bowl full of vodka. “Drink this, and you’ll soon feel better.”

I drank it perhaps too quickly, and soon felt strangely better.

Auden had a cracked and wrinkled face, like a baked mudflat, and he told me that he would soon be dead. (Indeed, he died a couple of years later.)

“I’ve learned a little in my life,” he said. “Not much. But I will share with you what I do know. I hope it will help.”

He lit a cigarette, looked at the ceiling, then said, “I know only two things. The first is this: There is no such thing as time.” He explained that time was an illusion: past, present, future. Eternity was “without a beginning or an end,” and we must come to terms with what underlies time, or exists around its edges. He quoted the Gospel of John, where Jesus said: “Before Abraham was, I am.” That disjunctive remark upends our notions of chronology once and for all, he told me.

I listened, a bit puzzled, then asked: “So what’s the second thing?”

“Ah, that,” he said. “The second thing is simply advice. Rest in God, dear boy. Rest in God.”

Auden’s two points of wisdom have taken decades to absorb. He was telling me, I think, that our frantic search for meaning in the calendar and clock — the race against time — is foolish in the context of a larger universe or God’s eternity (one can define “God” in so many different ways). “Ridiculous the waste sad time,” wrote T. S. Eliot, urging us toward “the still point of the turning world.”

The advice to rest in God seems more and more relevant to me. It invites us to relax into the power of the universe that sustains us, that holds us up, embraces us — even to the point of death. This is, I think, the Easter message in a nutshell: trusting in God’s power to transform our lives into something better.

As I left his cottage that night, Auden asked me to join him at the college chapel that weekend for Sunday worship. I agreed to this, and I’ve been going ever since. In fact, I’ve never been more grateful to Auden than now, in this time of plague and political as well as economic apprehension, with the Easter season suddenly upon us.

Resurrection thinking has never seemed more relevant.

[ad_2]

Source link