[ad_1]

In 1893, Ida B. Wells published a pamphlet titled “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.” The expo, which lasted for six months, was held in Chicago and was meant to chart the trajectory of the Americas in the four hundred years since Columbus had arrived. Though a handful of African-Americans had individual exhibits at the fair, there was none specifically dedicated to the history or the accomplishments of African-Americans as a people. Wells secured contributions for the pamphlet from Frederick Douglass, the educator and journalist Irvine Garland Penn, and the lawyer and activist Ferdinand Lee Barnett. Together with Wells, they wrote about the ways in which black life could enrich the fair’s official version of American history, which, as Wells noted in the pamphlet’s introduction, had rendered invisible the contributions of black people to the American might that the fair was intended to celebrate. “The wealth created by their industry has afforded to the white people of this country the leisure essential to their great progress in education, art, science, industry and invention,” she wrote. Wells and Douglass distributed the pamphlet at the fair’s popular Haitian Pavilion, and, eventually, the expo’s organizers held a “Negro Day.” Wells declined to participate.

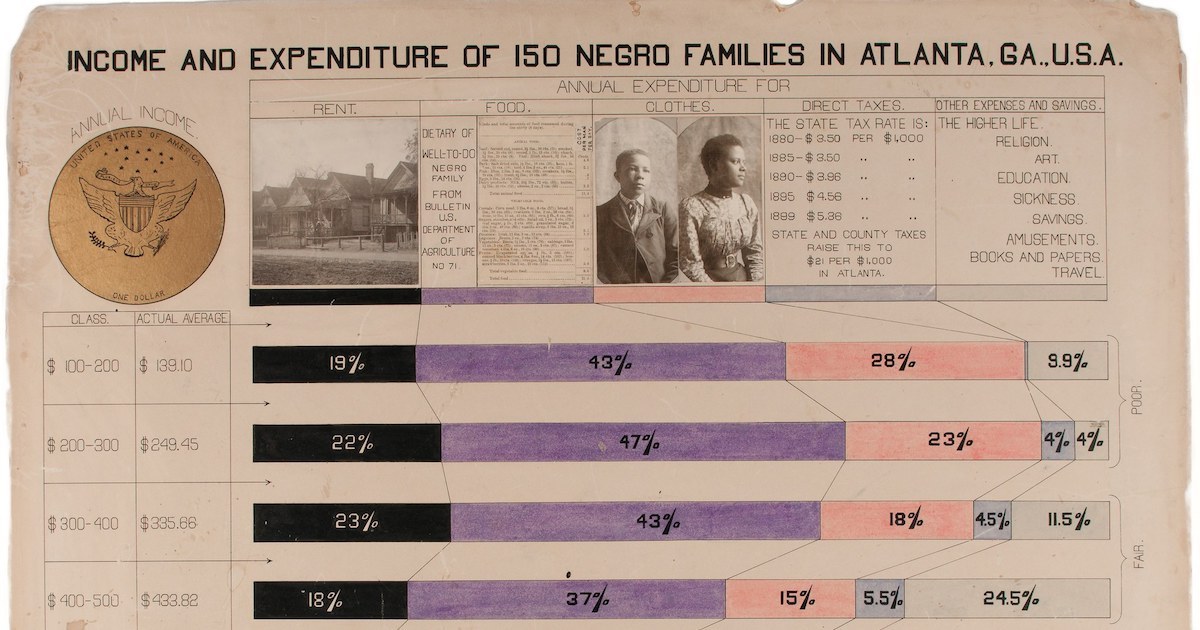

Seven years later, another World’s Fair was held, in Paris. This time, the African-American lawyer Thomas Calloway worked with the expo’s American delegation, and he invited W. E. B. Du Bois to oversee an exhibition on black life. Du Bois was teaching sociology at Atlanta University, which later became Clark Atlanta University; in four months, he and his curatorial team put together a multimedia presentation that testified to the eclecticism and resilience of their community. They conceived the exhibit as a sort of cabinet of curiosities, full of juxtapositions and visual echoes, in which you could wander and drift, zeroing in on whatever caught your eye: a small statue of Frederick Douglass; a bibliography of African-American writings, containing fourteen hundred titles; four bound volumes of more than three hundred and fifty patents secured by African-American inventors. All of these items orbited an argument about the capacity of African-Americans to withstand, and fight, injustice, with pride, dignity, and joy.

[ad_2]

Source link