[ad_1]

This “Letter from London” was written in April and appears in the Summer 2020 issue of ARTnews.

Following a succession of qualified Black cultural icons and personalities—including actor Idris Elba and architect David Adjaye—who appear unburdened by the historical context of such a distinction, Steve McQueen accepted the award of a knighthood for “his service to both the art and film industries” in England earlier this year. It was his third British order of chivalry, following an OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) in 2002 and a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 2011.

Given his reticence to defer to the monarchy and the legacy of the British Empire, McQueen confessed in an interview with the Guardian that “it wasn’t an easy decision” to accept the designation. “I can see that some people would feel hesitant,” he said. As to why he went through with it: “this [knighthood] is one of the highest awards the state gives out, so I’m going to take it. Because I’m from here and if they want to give me an award, I’ll have it, thank you very much,” he said, “and I’ll use it for whatever I can use it for.”

The Black British anti-colonial newspaper International African Opinion argued in the 1930s that “the judicious management of the Black intelligentsia, giving them jobs, OBEs and even knighthoods” in attempts to combine cultural diversity with civic order is a political tactic to pacify a nation into acceptance of imperial rule. Since then, the appointment system overseen by the Cabinet Office’s Honours and Appointments Secretariat has been increasingly denounced by the public and even members of Parliament as anachronistic, insensitive, and class-bound. In 2003, poet Benjamin Zephaniah rejected the offer of an OBE, writing afterward, “OBE me? Up yours, I thought. I get angry when I hear that word ‘empire’; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds me of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised.”

In her 2016 book, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, scholar Christina Sharpe wishes for her readers to understand the status of “Black peoples in the wake with no state or nation to protect us, with no citizenship bound to be respected.” So how might our society better acknowledge those who serve it well? For McQueen, a survey at Tate Modern, the biggest nod from the establishment for any British artist, could count as a just reward. Upon entering McQueen’s show there—opened in February and touted by Tate as “the first major exhibition of Steve McQueen’s artwork in the UK for 20 years”—a visitor was greeted by two mammoth dual-screen installations, fitting for a filmmaker, in a setting almost pitch-dark and equipped with purpose-built cinemas to host a small number of viewers at a time.

But something important was missing. McQueen’s first major film, Bear (1993), was initially presented at the Royal College of Art and then at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in the leadup to the artist’s Turner Prize win in 1999. Recorded in black and white, the tension-filled silent film features two Black men (one of them McQueen) wrestling naked and interlocking over 10 minutes in an unexplained fight. Jovial in some moments, rough and antagonistic in others, Bear might be McQueen’s most overt commentary on issues of race, masculinity, and homoeroticism that are still very much omnipresent in England today. So why was it left out at Tate?

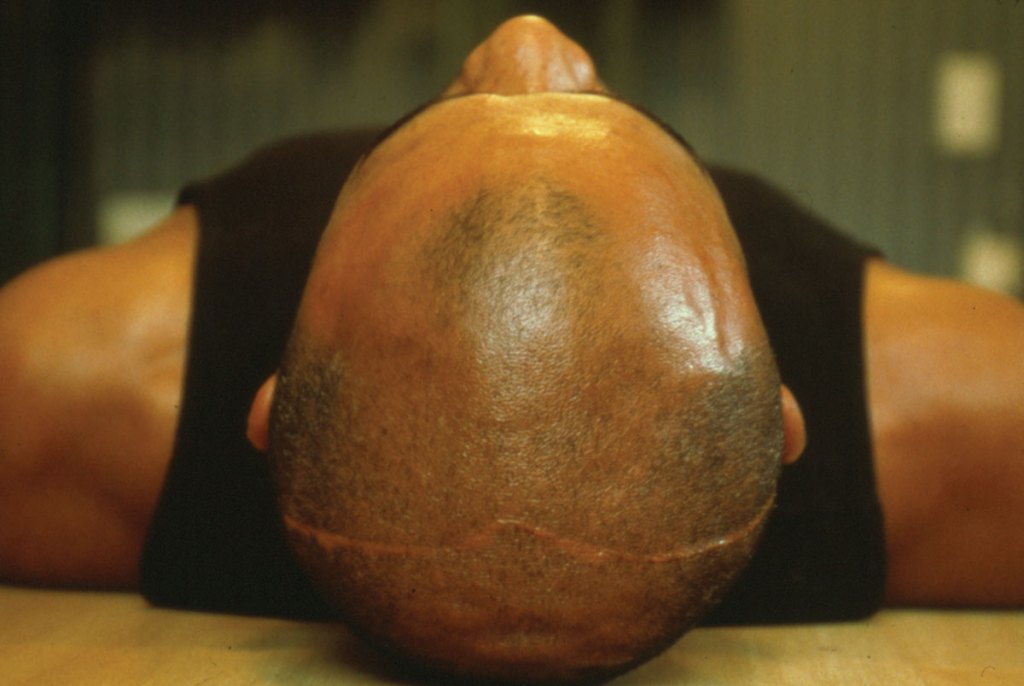

Instead, nearly all the work included was made after 1999, picking up from where McQueen’s Turner Prize show that year left off. And 7th Nov, from 2001, is the work that has lingered most prominently since, given the state of the union in England as it stands nearly 20 years later. The 35mm work focuses on McQueen’s cousin Marcus in a static image of his tanned shoulders and the top of his black shirt below a bald scalp with a long keloid scar spanning the circumference of his head. Marcus seems secure in a physical and mental space of his own as he narrates a story to new ears in Black London vernacular.

His tone isn’t smooth, but it soothes as, in one 23-minute take, he recounts the day he accidentally shot and killed his younger brother while trying to engage a safety lock on a gun. (The title 7th Nov refers to the date of the incident.) As Marcus details scenes including a “four-foot stream of blood” leaving his brother’s body, the work is suffused with a certain heaviness but not quite sadness. Marcus leaves no room for self-pity or disarming emotions, and his tonality never wavers as he occasionally addresses the viewer to ask: “Do you understand?”

Matt Sayles/Invision/AP/Shutterstock.

As the first Black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture (for 12 Years a Slave in 2013), McQueen remains a major figure in England long after he first evaded the invisible holes of a working-class London social-housing estate through, as he wrote in a remembrance for The Big Issue occasioned by the opening of the Tate show, “hard-headedness and luck. Or hard-headedness and talent.” In a Financial Times interview around the same time, McQueen also professed a sense of solidarity with the figurative and literal sacrifices of predecessors before him, so that “people like Stephen Lawrence”—an-18-year-old aspiring architect who was knifed to death by a racist mob of white men at a South London bus stop in 1993—“didn’t die in vain.”

Unsatisfied with the state’s response to Stephen’s murder, the Lawrence family called for help from Black leaders at the time including Nelson Mandela, then the president of South Africa, who met with them and called on the government to do more. Suspects were charged with the crime, but the charges were dropped, and, almost four years later, a retired judge and former soldier oversaw a public inquiry that would go on to describe the Metropolitan Police’s response to Lawrence’s killing as “marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership.”

©Tate, London

Though two suspects were convicted in 2012, Lawrence’s death and its reverberations—like country-wide riots sparked by the murder of Mark Duggan in 2011 and the negligence shown during the Grenfell Tower fire that claimed more than 70 lives in 2017—remain in the national memory. The anniversary of Lawrence’s passing was commemorated by many in April, nearly two decades after the fact.

Lawrence’s Jamaican-born mother, Doreen Lawrence, accepted an OBE in 2003 for her service to community relations. And she is also commemorated in Chris Ofili’s 1998 painting No Woman, No Cry, included in the artist’s Turner Prize exhibition, and now in the permanent collection of Tate—with Doreen shedding tears, each bearing an image of her son in phosphorescent paint, amid the words “RIP Stephen Lawrence 1974–1993.”

To consider history of this kind in artwork of such recent vintage is to better understand England’s legacy of life—in words borrowed from Sharpe’s In the Wake—“lived in, as, under, despite Black death.”

The commercial success of just a handful of Black British artists of the stature of McQueen and Ofili makes clear that the trajectory of art as a career is still unstable, with little assistance and still no readily available blueprint for younger generations to follow. Until Tate Modern opened in 2000, London was the only major European city without a public art gallery for modern and contemporary art. In the 1990s, the London-based Young British Artists’ fame was disseminated abroad, giving the sense of London as a growing center of artistic exchange, but in fact London’s art world was open only to some.

McQueen studied at Goldsmiths College at the same time as Damien Hirst and other YBAs, but he would later attest (in the same Guardian interview around his Tate Modern opening) to only a single interaction with them. “I went for a drink with some people once,” McQueen said. “That was it. It was … isolating.” Once Charles Saatchi became the preeminent patron of the YBAs, known to buy out entire shows of work, the group came to include its only Black member, Chris Ofili, at a time when his distinctive use of elephant dung within his work was very much in its ascendancy and receiving mixed reviews. Concurrently, the exposure of nonwhite British artists was collapsed into a postcolonial or identity-based construction, and the general discourse surrounding their work was tone-deaf and absent of any structural understanding of the unavoidable politics that informed it.

Courtesy Autograph, London.

One example of a measure of success for a Black artist in the U.K. that predates McQueen and Ofili is Rotimi Fani-Kayode, who figured in “Masculinities: Liberation through Photography,” an exhibition that opened this past February at North London’s Barbican Centre with a focus on gender constructions in work by more than 50 artists from the 1960s to the present.

Born in Nigeria, Fani-Kayode presented as Black and gay in the 1980s, when he lived in London with his lover and collaborator, Alex Hirst. Experienced with the kind of contentiousness that greeted Black artists in the U.K., Fani-Kayode once wrote about “Europeans faced with the dogged survival of alien cultures” and their tendency to act “as mercantile as they were in the days of the Trade.” Such observers, he continued with disdain, are on a mission to “sell our culture as a consumer product.”

“The ’80s were a critical decade for Black British photography.”

In his 2019 book, Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time, British curator Mark Sealy employs his concept of “racial time” to “signify a different but essential colonial temporality at work within a photograph”—an idea that applies to images by Fani-Kayode. The ’80s were a critical decade for Black British photography, as evidenced by five pictures by Fani-Kayode in “Masculinities,” including some of his last work before he died from AIDS-related complications in 1989. His studio-based photography, much of it self-portraiture, is of a theatrical, sensual, and serious nature—and it plays with conventions and expectations too: In Untitled (Offering), the conception of the hyper-eroticized Black phallus is represented by a pair of overly large scissors.

In a passage quoted in the exhibition catalogue, American theorist bell hooks encourages us to conceive of the task of altering the image of Black men—in the lineage of Fani-Kayode and others including Steve McQueen later down the line—as a collective enterprise. “Collectively we can break the life threatening choke-hold patriarchal masculinity imposes on Black men,” hooks writes, “and create life-sustaining visions of a reconstructed Black masculinity that can provide Black men ways to save their lives and the lives of their brothers and sisters in struggle.”

A version of this article appears in the Summer 2020 issue of ARTnews under the title “Letter from London: Knight of Honor?”

[ad_2]

Source link