[ad_1]

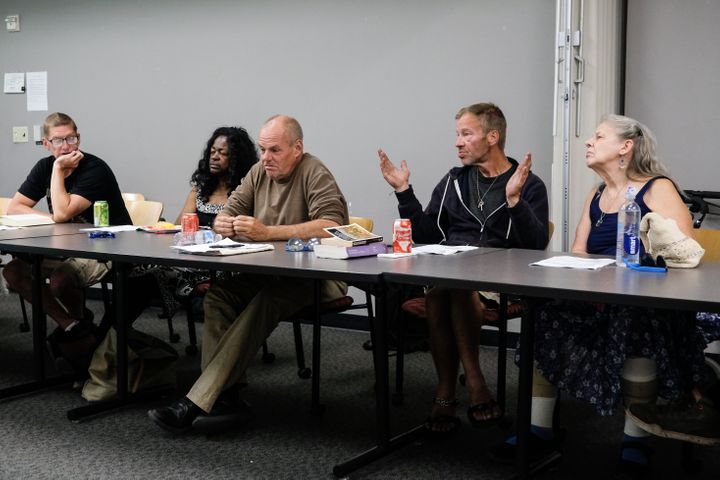

On a hot Monday morning in May, 63-year-old Donna Ware sat down in the meeting room at the Terrazas Branch library in East Austin, with her small service dog, Pilaf, sitting in her lap. She was there with a dozen other people who are currently homeless or have experienced homelessness.

Ware is a member of the Homeless Advisory Committee of Austin, a unique attempt to solve the city’s growing homelessness problem by soliciting advice directly from people who know firsthand what it’s like to live on the streets.

She joined two years ago, at the recommendation of her PTSD counselor. At the time, Ware — a former substitute teacher who had become homeless after losing a lengthy and expensive eminent domain eviction lawsuit — had no income, and had been in and out of the hospital. She managed to stay off the streets only by walking around a Walmart during the night and taking a bus the next morning to her air-conditioned storage unit, where she slept during the day. If she participated in the committee, her counselor told her, she’d get a $40 Visa gift card at each biweekly meeting, along with the chance for her voice to be heard.

The committee was created by the city of Austin’s Office of Innovation in 2017, part of a larger effort by the city to stem the rise in homelessness. “We knew we wanted a group of people with lived experience that we could engage with, and that we could generate ideas with and test and prototype those ideas with to see if they actually met people’s lived realities,” said Kerry O’Connor, Austin’s Chief Innovation Officer.

At the committee’s bimonthly meetings, members talk about recent challenges they’ve faced, participate in creative workshop exercises and brainstorming sessions, and vote on recommendations to help the city determine policies that address homelessness. It’s the only committee of its kind in the United States.

“It’s been enlightening, encouraging and affirming,” Ware said in an interview after the meeting in May, with the gleaming glass towers of Austin’s downtown skyline looming behind her. “I have a voice, and not just for myself, but for the people.”

But the sluggish pace of civic bureaucracy has often left her frustrated. In the two years since Ware joined the committee, she has seen few tangible changes result from the committee’s work, and several major efforts by the city to address homelessness have yet to come to fruition.

The city has not yet hired a permanent homelessness czar after announcing plans to do so two years ago, and construction of a new homeless shelter in South Austin has stalled amid intense opposition from Austin’s not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) crowd.

All the while, Austin’s homeless population continues to grow. The city counted 2,255 homeless people on the streets on a single night in 2019, a 5% increase over last year’s count (the actual number of homeless in Austin is believed to be much higher, since the annual point-in-time tally does not count homeless people who are hospitalized, incarcerated or in temporary housing).

Many of the advisory committee’s members — including Ware, who is mostly sofa-hopping now, staying with friends and family — remain without stable housing themselves. Ware said one committee member who had been homeless for several years finally received housing from the city last winter, but passed away not long after.

“There are many homeless people who will die before something gets done,” Ware said. “Things can be done. We’re not a poor city. I could understand it if we were in Detroit. But this is Austin. We’re one of the meccas, the new Silicon Valley — we ought to want to do something to end homelessness.”

The committee has mostly been focused on small-scale projects, such as building and testing a toiletries delivery system and creating a “Coping Skills Zine,” a booklet that includes information on how to cope with homelessness. But their latest proposal, which calls on the city to establish public storage centers so that people who are homeless have safe, accessible lockers to store their belongings, is probably their most ambitious idea yet.

Over the course of several meetings in May and June, the committee shared how lack of affordable, accessible storage has affected them. There were missed appointments, because they had no place to keep their things or could not access important personal documents. One committee member said he once came back from a job interview to find his things stolen. Another said she pays $200 for a storage locker, money that would be better put toward a home. Several members spoke of recurring back injuries that resulted from carrying heavy bags full of their personal items.

The committee proposed storage facilities that would be centrally located along major bus lines, and would include lights and emergency call buttons, the use of heat-resistant building materials to counter the scorching Austin summers, mail slots, and an online locker reservation system.

“The feedback they provide is invaluable,” Mark Janchar, a user designer with the city of Austin who has been working closely with the committee on its storage proposal, said. “We can’t see things with their eyes, and then as soon as they explain it to you it makes so much sense. It’s a great empathy-building tool. It creates this pathway for you to see homelessness in a personal, humanizing way.”

A few weeks later, the committee’s storage ideas were approved by the Downtown Austin Community Court Advisory Board, which oversees the committee. It recommended the city council consider approving funds for the proposal.

It was a major success for the Homeless Advisory Committee, and a reason for optimism among its members. Still, even if the city council votes soon to approve funding for the project, the storage lockers will likely not be up and running anytime soon, as the city would first need to determine potential locations and designs — a process that typically moves slowly.

“A lot of people on the council hold resentment and anger, because there’s not anything happening and nothing is actually changing,” committee member Lyric Wardlow, 21, said. “I want to believe in our city, because it’s such a growing, big city with so many things going on.”

Wardlow’s experience with homelessness started when she was a child and her mother was evicted. She and her mother couch-surfed and slept in shelters until she was 17, when she left on her own. Since then, she has found steady housing while working as an advocate for youth and the homeless.

She questions why a city with such a profitable tourism industry — last year’s annual Austin City Limits Music Festival, for example, had a $264.6 million economic impact — doesn’t redirect more of that money toward issues like homelessness.

“It confuses me,” Wardlow said. “You’re not taking parts of that [tourism] money for the homeless shelter two blocks down [from the tourist strip] to take care of the homeless people outside. There’s all these things the city could do, but we’re spending it on traffic and building more stuff instead of supporting the homeless community.”

It’s also clear that some Austinites perceive the homeless population mostly as a threat to their own quality of life, which has slowed efforts to help the homeless. Should the committee’s storage locker proposal ultimately be approved by the city council, they may face resistance while finding permanent locations for the facilities.

“The biggest challenge for that is NIMBYism,” Janchar said. “It’s the same thing with the shelters. Everyone wants one, but not in their district. Wherever it will be put, people are going to fight it.”

At a city council meeting on June 20, the week after the committee’s storage proposal was passed by the community court board, a pair of high-profile homelessness issues were on the agenda: A vote on whether to ease controversial ordinances which made public camping and panhandling illegal — measures which critics say unfairly criminalizes the homeless — and a vote to determine the location of the new $8.6 million shelter that had been planned for South Austin.

Homeless advocates gathered with signs on the steps of city hall to support the votes, but there was also intense opposition to both measures. A petition opposing the new shelter had more than 3,000 signatures (it now has over 3,500).

During a five-hour long period of public testimony, one speaker accused homeless people of “terrorizing” her neighborhood. “I have a convertible, and I’m afraid to drive it because I’m afraid what they’ll do to me when they panhandle,” another speaker testified, through tears.

At 2 a.m., the council finally voted to ease the ordinances and to finalize the shelter’s location, drawing a mix of cheers and boos from the crowd. But the council’s decisions may be short-lived. The following Monday, Texas Governor Greg Abbott (R) threatened to overturn the city council’s votes. “At some point cities must start putting public safety and common sense first,” Abbott tweeted.

The city council meeting was emblematic of the fraught tensions over homelessness in Austin, and of what the Homeless Advisory Committee is ultimately up against. At odds are this city’s proudly progressive ideals — the kind of thinking that led to the creation of the committee — and the realities of what is needed to address Austin’s growing homelessness crisis.

“We know what the answers are,” Austin Mayor Steve Adler said toward the end of the city council meeting. “The only question for us is whether we have the political and community will to actually take steps. The status quo on this issue is killing us.”

Ware isn’t sure how much longer she and her dog can keep living without stable housing. “If I don’t have housing within the next year or two, Pilaf and I, we’re just going to jump off a bridge,” Ware said, perhaps half-joking. “All dogs go to heaven, and I told Pilaf he’d see mommy there. I’m not standing around homeless for another five years.”

She described her life as a constant struggle to hold on to a sense of personal identity outside of her homelessness. Her participation on the committee has helped her with that, but it has also shown her just how hard it is to create change in Austin. She likened the Homeless Advisory Committee to a bicycle with a rusty chain. “It’s still a very nice bike, but without the chain being fixed, it’ll never have any potential,” Ware said. “We’re good, we’re innovative, we’re thinking through things and coming up with stuff. But if we don’t fix what’s broken, we’re not going to go any further.”

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to thisnewworld@huffpost.com.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link