[ad_1]

Since the Covid-19 crisis hit the United States earlier this year, there have been numerous comparisons to HIV/AIDS, the last major pandemic this country faced, whether it was it was writers like Andrew Sullivan pointing out that the pages and pages of obituaries in a newspaper in Bergamo, Italy—especially hard hit by the coronavirus—reminded him of similarly sized obituary sections in gay newspapers of the 1980s, or talking heads like Rachel Maddow consulting Taiwanese-American HIV/AIDS researcher David Ho. Over the past month, there have also been comparisons to art associated with the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ’90s, in context with the art of numerous past pandemics.

Recently ARTnews spoke with art historian and curator Jonathan Katz, who specializes in art of the AIDS era, and asked him how some of that art might resonate with what is happening today—whether it has to do with the loneliness associated with social distancing, the disorientation associated with not fully understanding the mode of transmission and therefore how to protect oneself, the importance of paying attention to marginalized communities (the underprivileged, those who are incarcerated), and the agonies of dying alone.

In our interview, Katz emphasized some of the similarities between this coronavirus and AIDS—and, importantly, some of the key differences.

The shock of death is, of course, a similarity. “I remember one particular issue of the Bay Area Reporter, the gay newspaper for San Francisco, with about six pages of news and 25 pages of obituaries,” Katz said. “So it was a big, fat issue. And I got all excited about the news. And then I realized that it was almost all obituaries. That was almost an everyday occurrence. The thing I’m reminded of is the completely unpredictable nature of this as a disease.”

Fear of and distancing from those who have or are suspected of having the virus counts as a similarity, the key difference being how AIDS became linked to identity . “In the early days of AIDS, all forms of contact were made fraught,” Katz said. “I remember people going home and being told that they were not welcome. I remember trashy newspapers saying things like: If my son tries to come [home], he is going to get shot on my doorstep, all that kind of stuff. And this was, by the way, not only in terms of people who had verifiable AIDS but just gay people. These reports were cynically instrumentalized by the Republican political movement as a means of wedge politics, of assuring a strong majority, and it worked.”

AIDS, Katz noted, was “an identitarian disease, and by that I mean that it was understood to destabilize the family, to lead to an early, pathetic, lonely death. In other words, it was used to reify and reanimate all the stereotypes around homosexuality that were being fed by a Republican majority at that moment.”

“I’m very sad about what’s happening,” Katz continued, “but I’m also grateful that, thus far, despite Trump calling it ‘the China virus,’ we have not made this disease an explicit aspect of identity politics. The few exceptions to this rule now cloak their unfashionable racism in current events to hide its bitter taste. That said, we have ever clearer evidence of the pandemic’s ideological character, as it’s still overwhelmingly the already marginalized—in class, racial, and legal status terms (such as prisoners or refugees)—who must deal with the brunt of it. But the international quality of this disease carries one tiny bright spot, which is the qualities that we have of being united in our fear of exposure.”

And then, of course, there is the sense that lingers: Why did I survive? Earlier this week, the New York Times published a report on survivors of coronavirus that pointed to the element of guilt. As Katz confirms, this is certainly something that characterizes the AIDS era in the U.S., even today: “I’m alive today. Why am I alive today? Most of my friends from that era died.”

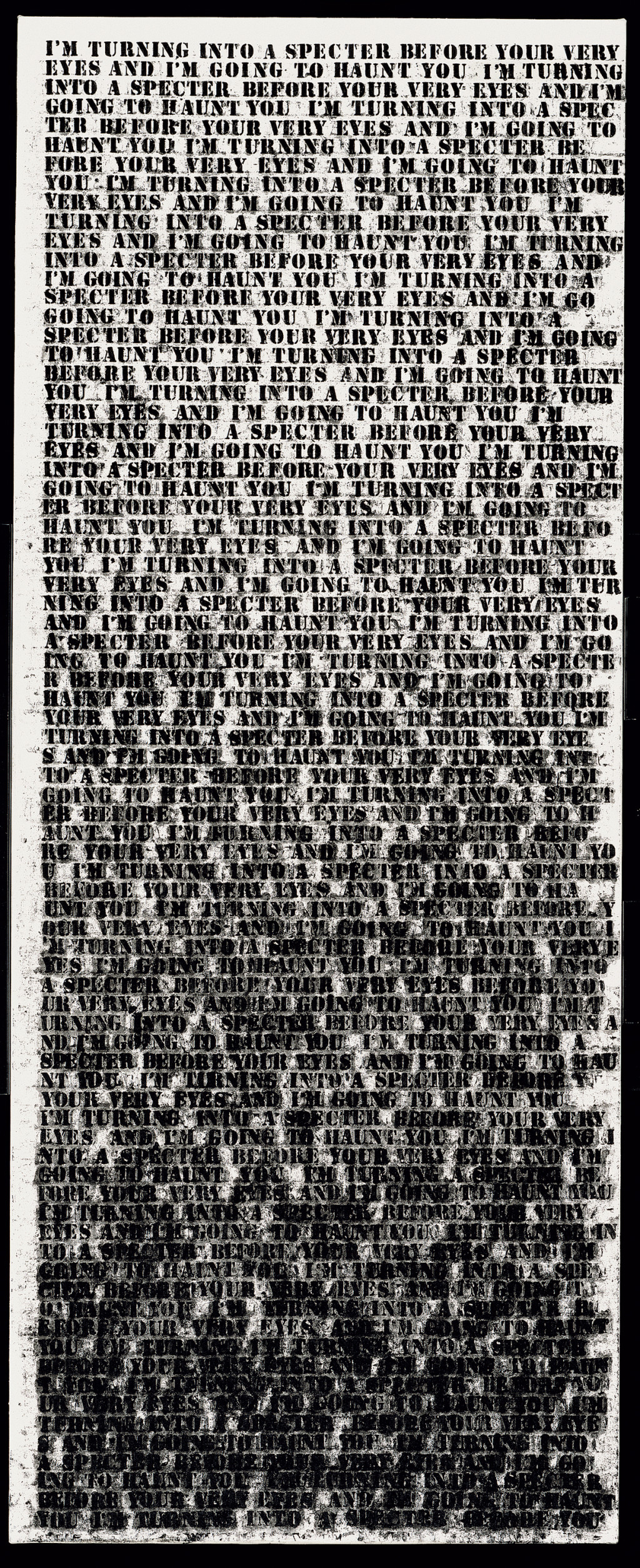

In the slideshow linked above, Katz, who in 2016 co-curated the traveling museum exhibition “Art AIDS America”, walks us some artworks of the AIDS era that, in his view, can be grouped into three approaches that may help us to comprehend what is happening around us today: the viral approach, the elegiac approach, and the political approach.

[ad_2]

Source link