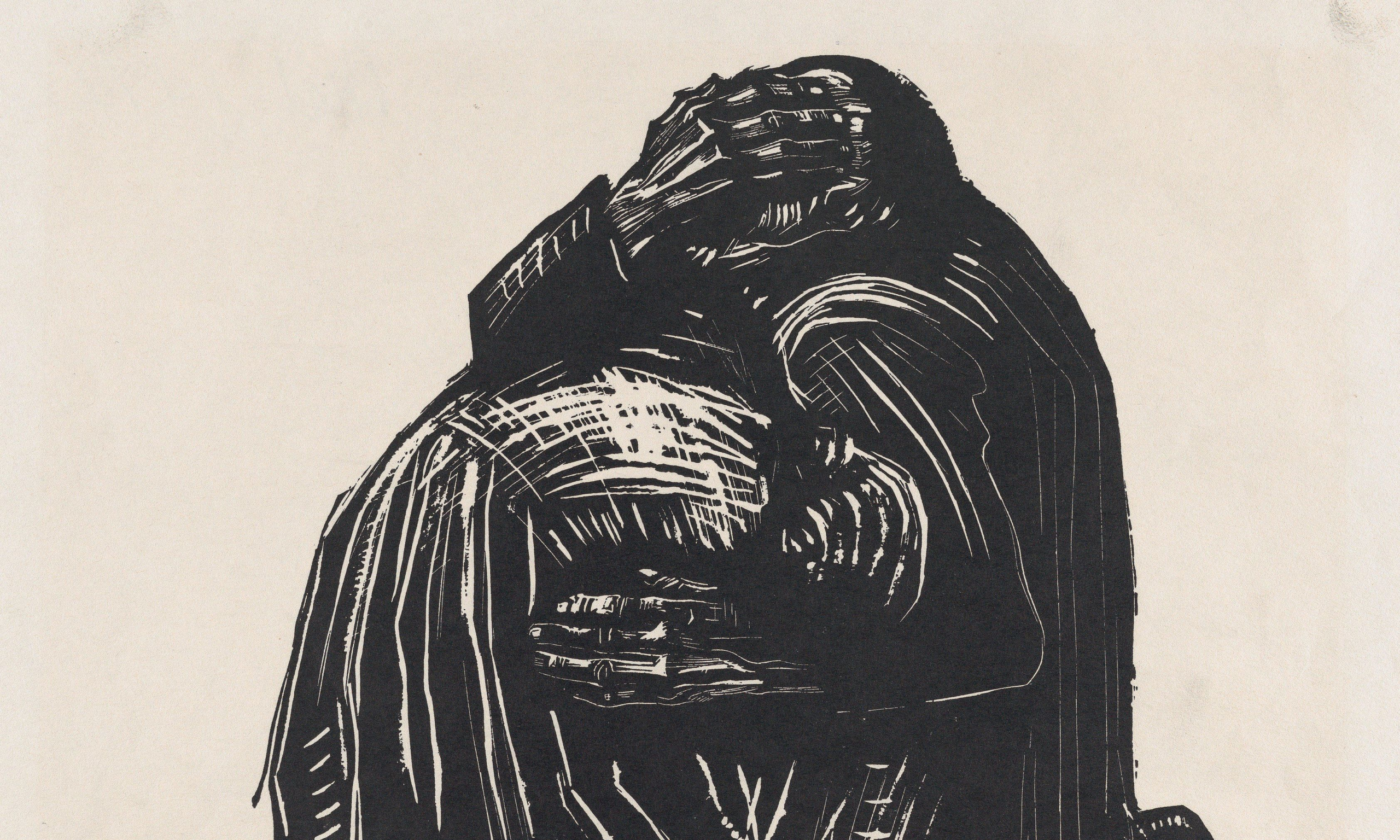

Käthe Kollwitz, The Parents, a woodcut from the artist's War series of 1921-2

agefotostock / Alamy Stock Photo

May you not live in interesting times, goes an apocryphal Chinese prayer. The implication is that interesting times are also dangerous ones. There is no denying the volatility of the world right now. There is war in Ukraine and deadly conflict in the Middle East. Surrounding it all is the ultimate existential threat of global climate catastrophe.

The question is, how should artists and cultural organisations respond to world crisis? There can be no absolute rule on this. Some artists believe that art is only valid when it is political. Others feel that their work, such as it is, constitutes their response to life. Many artists feel that politics is inappropriate in the world of art. Artists cannot be prescribed for.

But world events have a way of making unengaged art somehow irrelevant and even reactionary. An artist in the Germany of the Third Reich would have found that politics had moved permanently into the air they breathed. To be above politics then would in effect have been sanctioning the horrors going on around you. There is a limit to the pose of artistic neutrality.

The true artist responds to world events in the light of their conscience. Art is both a delicate and a resilient thing. It can bear all kinds of weight. If the art fulfils the fundamental conditions of its existence, it can do whatever it wants. So long as it remains art and does not spill over into propaganda.

We have seen how resilient art is. Picasso used painting as an instrument against war. Shakespeare absorbed history into the body of his plays. Many great paintings have contemporary reality as part of their lifeblood. Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Manet, Kollwitz, Goya, Salcedo bore witness to the horrors of war and conflict.

As for cultural organisations the matter seems more complex, but they cannot avoid being morally conscious. The very nature of an artistic endeavour already implies a sense of justice and an active conscience. Such organisations are quiet shapers of public understanding.

Art organisations should therefore use their powerful positions to support causes that affect our moral health. They can do this subtly. Museums could stage exhibitions that raise those issues and help people think about them in enlightened ways. Theatres could put on plays that make us think about the moral conundrums around the crisis. We look to art organisations to reflect the underlying and the overt crises of our times as well as to remind us of the timeless dimensions of art and the human spirit.

Artists are the antennae of the human race. They sense what is coming. They interpret what is already here. They give a shape to the visible and the invisible crises that are befalling us. Art organisations fail in their duties if they, too, do not pick up on what the artists are tuning into, what they are reflecting consciously or unconsciously in their work. The timeless dimension of art transcends history and gives us an immortal perspective on the turbulence of our times. We need the tranquility as well as the engagement because this reflects what we are as human beings.

Artists and art organisations cannot afford to be on the wrong side of history. More than that, they should help the better future to be born out of war and chaos and injustice. Where the crisis is complicated with hundreds of years of tangled history, where the right side is not so clear, we could avoid making it worse by taking sides thoughtlessly. Perhaps the most powerful thing that organisations can do in such times is to contribute to the cry for peace.

We live in an age of escalating violence. But what we really need is more listening. Art teaches us to listen, to see, to wait for understanding. Politicians rush beyond the bounds of reason, carried on by ancient passions and grudges. People perish, the world turns upside down, and the seeds to the next cycle of violence are sown. But the cycle of violence must be broken. To do this we must return to the human. This is what art can teach power: that to go beyond the human is to create an inhuman world. We are not made to live in hate. Art should not foster hatred. In a world where even religions can breed hate and wars, we need a new value that can unify us, and bring us together in creativity and co-operation.

Now more than ever, nations and peoples need to come together. For beyond the colonial ambitions, beyond the ancient hatreds, a new spectre haunts the world.

Perhaps the climate catastrophe will give us the opportunity to see ourselves in a new light. It might teach us to have a new respect for one another and for the planet. It might teach us the true meaning of love, the eternal lesson of art.

• Ben Okri is a poet, novelist, and playwright. His latest novel is The Last Gift of the Master Artists. His latest book is Tiger Work: Stories, Essays and Poems about Climate Change