[ad_1]

Change is constant, but progress is a slow process, especially in the fight for civil rights. Rashad Robinson, president of the advocacy group Color Of Change, knows this firsthand.

The New York native began his activist work early, staging his first protest at age 14 against local stores that were discriminating against young people. The demonstration got media attention and led to a face-to-face meeting between the kids and business heads, prompting them to change store policies.

For Robinson, it was an early look at how strategic planning and persistence can win results.

Little did he know then that he’d go on to lead one of the largest online social activism nonprofits dedicated to eradicating the everyday injustices black people face. Since taking the helm of Color Of Change in 2011, Robinson has helped to spearhead advertising boycotts that have included pressuring Fox News to cancel Bill O’Reilly’s show after the host spewed dangerous rhetoric about black people. (Fox News finally canceled O’Reilly’s show in 2017 after revelations of workplace sexual harassment.) Robinson also campaigned for Sony to drop R. Kelly and mobilized black voters during the 2018 midterm elections.

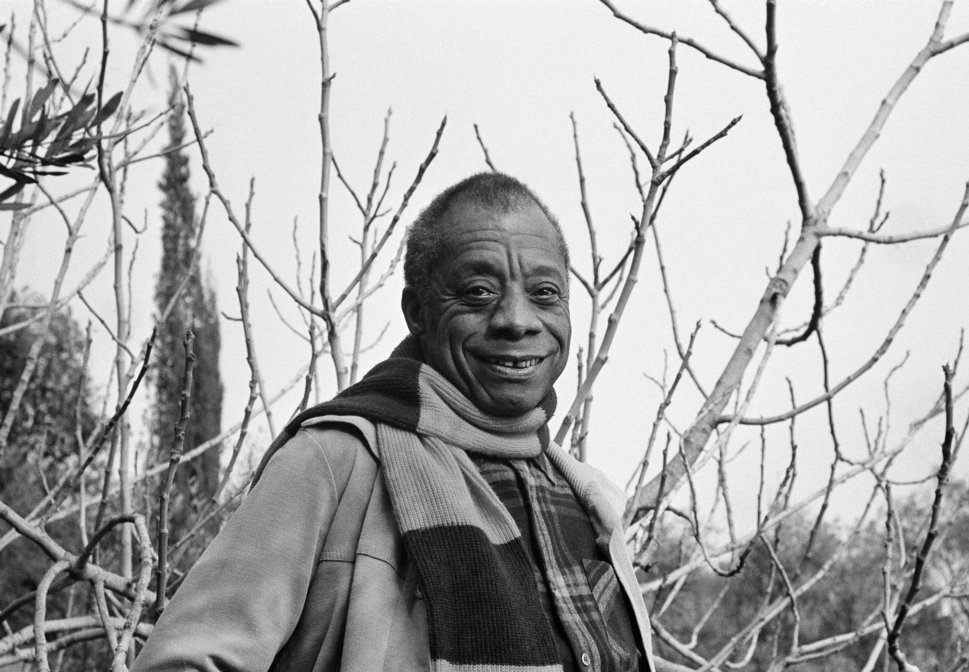

As a part of the “We Built This” photo series, HuffPost is highlighting Robinson’s work as a change agent and black history maker of today. Robinson spoke to us about his passion for pursuing justice, the importance of strategy and finding peace while fighting the good fight.

At Color Of Change, we’ve built a force of 1.4 million black folks and their allies of every race that take on the type of issues, the type of moments that translate the presence that black people have in the world into the power to actually change the rules. Winning campaigns every single day that change the way that black people are treated and create real consequences for racism and unequal behavior in society.

One thing that I found really interesting is that you started your career in activism at an early age, I believe it was like 14?

Yeah, I grew up in a community on eastern Long Island, it was about 7 percent black. My family got through the Great Migration from southern Virginia and North Carolina. My great-grandparents got there, they were farmers in the South and became farmers on Long Island. When you live in a community like that you’re always organizing, you’re organizing to get someone on the school board so issues infecting black people are dealt with, fighting to get someone on the town council so that your garbage gets picked up and our street gets plowed. So, I learned from an early age that concept of power, also the concept of coming together to build that collective power — not individual people acting alone, but bringing people together. From a really early age, I was knocking on doors for candidates, I was sometimes — even earlier than 14, much earlier than 14 — going to local NAACP meetings with my parents because they didn’t want to pay for a babysitter. My brother and I became activists in some ways, not because it was always preordained, but because it was very much part of the life that we were part of.

Was there a particular person or event that activated that passion?

When I was a junior in high school, a set of local stores decided they didn’t want to allow young people in during lunchtime. They claimed young people were stealing, and then there was a whole lot of stories that actually it wasn’t the young people that were stealing. Instantly, because of everything I had learned and been part of and watched from the side, I knew there was something wrong about that, that they couldn’t just do that. I remember reaching out to the ACLU and other folks. What ended up happening was I built a protest and organized my fellow students to protest. We protested Rite Aid and the record store that wouldn’t let us in.

We were on the front page of Newsday, all the local New York TV stations came down. I learned really early on how media loves kids and animals, and they followed us. It ended up in a face-to-face meeting with the executives of those stores. They backed down and changed their policies. Very quickly I not only got a sense of what it meant to be part of something that someone else built, what it meant to [not only] read about activism, but to actually do it and to see that there was both a passion and a willingness of people to follow a plan and a vision. And that people wanted to be asked to do something. Folks were complaining, folks were annoyed, folks were frustrated. There was something about everything that I had experienced, somewhat through osmosis, somewhat through actually looking for it, that translated into being in the right place at the right time.

From that moment forward, I’ve always believed deeply in people coming together to translate their own power into action, to fight for their own power. Those who are marginalized need to be at the center of their own journey and the center of their own struggle. My whole life has really been centered on that, and centered on being part of that, and being part of it with people.

That kind of foreshadows the work that you’re doing today. One thing that I really respect about Color Of Change — that I really didn’t even realize until recently — was that it was founded post-Hurricane Katrina. Why is that significant to the organization’s approach to social justice?

Yeah. Hurricane Katrina was a flood that was caused by bad decision-makers that turned into a life-altering disaster by those same bad decision-makers. Black people were literally on their roofs begging for the government to do something and left to die. The thing about Katrina was that it illustrated things that people already knew: geographic segregation, generational poverty, the impacts of what had happened to systems like climate and justice. But at the heart of Katrina, no one was nervous about disappointing black people. When institutions like media, government, corporations are not nervous about disappointing your community, it doesn’t matter what kind of research report you have, or even what legal case you have, if you can’t implement it. It doesn’t matter what our friends in Silicon Valley create — you can’t research your way, or legal your way, or code your way, or even nonprofit executive-direct your way out of a crisis like that.

There was an idea that we needed a new type of infrastructure to translate the energy and the outrage of people who were watching what was happening on their screens, but the only thing they were being told to do was give money to the Red Cross. What does it mean in these moments of outrage to bring people together to fight for something that can change the systems and the structures that are holding people back? Van Jones and James Rucker, the founders, sent a single email to 1,000 people asking them to join the movement. Over the course of these years since we were founded, since Hurricane Katrina, we’ve grown into a force of 1.4 million black folks and their allies, and every single day we’re finding the opportunities to help people be powerful on the issues that matter most to them.

Color Of Change is unique because it’s one of the first online organizing groups that we have seen. And you’ve gone on to cultivate millions of people who support the initiatives and the work that you do. What does it take, and what kind of challenges you face as a leader of this organization?

One of the things that’s oftentimes a challenge is that every single day we’re hit with information from the radio, the television, the internet, and that information outrages us and excites us. The thing that we try to do at Color Of Change is give people something strategic to do so that we just don’t leave them in outrage, that we just don’t leave folks in venting mode, that we point them [to] the most strategic thing to do, and that we find ways to partner with folks at the grassroots level, people who are leading and working to amplify and give more visibility to those efforts.

But we can’t do everything, and sometimes they’re horrific and challenging and painful stories that we don’t have the capacity to take on. For me, that can keep us up at night. That’s why the strategy of responding to moments, building energy, and constantly trying to find the systemic pivot, is always important. Because we do want to change the rules, so what was once acceptable three years ago is no longer acceptable, and what’s possible four years from now is even greater. As long as we’re continuing to move the ball, then I think our value-add is clear. But I don’t want to be in a situation — and digital media can make this happen, where you’re in this. You know that game Whack a Mole at the carnival, where you hit something down and it pops up, and you hit something else down and it pops up? That is what digital media and social media can do. Different things are popping up and you’re knocking it down, and then you can think that you’ve done something that you actually haven’t done because you had a whole set of victories here, and there, and everywhere, but you actually haven’t changed the rules.

We have a really clear framework of not mistaking presence for power. Presence is visibility, awareness, retweets, it’s our stories on the front page of the newspaper. Presence is great. It’s not that presence is a bad thing ― we try to build presence all the time. But power — power is the ability to change the rules. Sometimes those are the written rules of policy, sometimes those are the unwritten rules of culture. But being able to change the rules means that we are moving the ball forward in a way that changes the systemic culture, and at the heart of it, creates a more human and a less hostile world for black people. When black people win, the history of this country has been that all of us win. The victories that black people have achieved structurally, politically, culturally, have been victories that communities across the country, and dare I say, when I travel overseas and work with other countries to model their campaigns and their efforts off of black movements in this country, that people around the world have looked to our struggles. I fundamentally believe that the investment in black leadership, the investment in black infrastructure and organizing, the investment in black people being not just present, but powerful, is an investment in making our democracy work for everyone.

It’s such taxing work, I think, as far as the presence versus the power and all of the successful campaigns that Color Of Change has been able to execute. What makes a successful campaign, and how do you use it to pivot to structural change?

What makes a successful campaign, first and foremost, is that we are responding to the needs and the aspirations and the outrage and the passion of our people. What we don’t want to do is be an organization that’s somehow sitting outside of our people. Every single day these campaigns travel and they move at the speed of people power. When Sandra Bland was found hanging in a Waller County jail cell and her traffic stop went viral, she was given that $5,000 bail, we mobilized our members to action, along with a number of other organizations around the country who were building efforts like, Say Her Name.

We mobilized our members and we were engaged with Sandra’s family. Hundreds of thousands of our members engaged in that campaign. We not only did petition deliveries at the Department of Justice, and phone calls, and actions to the district attorney, we also raised money online and sent private investigators down to Waller County, and actually worked with HuffPost to find all sorts of collusion between the district attorney, the judge, the bail bonds. Working across media, and people, and inside, and outside, and responding and giving people a way to deal with their frustration outrage. But, we also recognize that those in power were not nervous about disappointing us, so we recognized in that moment — along with a number of other moments like the work to fight Anita Alvarez, the former state’s attorney in Chicago who did so much to fuel mass incarceration in Cook County and allow police to run roughshod over the community — those situations all created a situation where we felt like we had to do something different in order to flex our power.

That’s when we built a whole campaign around district attorneys. Since we built out that campaign, the Color Of Change PAC has engaged deeply in over 15 district attorney races around the country, winning over 10 of those races in partnership with local communities. Mobilizing literally millions of voters to the polls and thousands of people to actually do door-knocking and phone calls, and phone banking, to reach voters and educate them about what district attorneys do and why they are important. In the process, [we began] to change the incentive structures for what district attorneys do. So, when you ask me what makes a successful campaign, it’s recognizing that these are not one-offs. This is about an ongoing drumbeat of building power for black people so that those in power recognize that there are gonna be consequences. Anita Alvarez, who ignored DNA evidence that exonerated black folks and suppressed the tape of Laquan McDonald being shot in the back, is no longer a district attorney because of local organizers on the ground, and Color Of Change members who came together and said, “Bye, Anita.” There are a number of other district attorneys who are at home trying to find other jobs. There are people in office now who recognize that they got there because of black people and black communities. The only way that they can stay there is by recognizing who they serve.

Our campaigns are about a long arc of building power, and while people may experience them online as one petition here, or asking folks to make phone calls here, or asking people to show up for this, there’s always a bigger vision of how we create enough of the energy, the action, the activity, that forces the system to have to change, for people to have to move and for decision-makers to have to be accountable.

This is around-the-clock work. How do you take care of yourself?

I keep getting this question lately. I’m wondering if the bags under my eyes are starting to show. I think about this a couple of ways. I sometimes get to talk to people who are athletes, or musicians who train to do that and are in the middle of the thing that they always wanted to do. In so many ways, that’s how I feel about what I’m doing right now, so there’s definitely aspects of the job that feel like work. As someone who got into this as a youth organizer, I never thought I would have to be running around raising millions of dollars to ensure that people got paid every two weeks and we paid our bills. That’s important, and that does feel like a job. There are other aspects of being the president of an organization that feels like a job.

And then there are things about what I do every single day that if I did not have this job I would be doing it in another way. I’d be volunteering, I’d be emailing people trying to figure out how I could get involved. For me, I constantly think about work-life balance, but I think about the word balance. I think about the word balance because balance means different things for different people, and what it takes for someone to be on that balance beam and stay on it is different for every person. I do not believe that anyone should stay in these jobs forever. I do not believe that this job is my life’s work. What I do believe is that in this moment I’m gonna give everything I can. I’m also gonna create for other leaders. I’m gonna create space and pipelines for others to have leadership, and opportunity, and visibility, because at some point, someone else should take this organization to the next level.

The same way that James and Van passed the baton to me, at some point someone else will take this. I believe that right now, in this moment, while I feel full of energy and passion and focus, that my commitment is to do everything I can and to leave everything on the field because this moment is so critical and the opportunity to shift the dynamics of what black people are facing feels so real.

Who are the black history-makers, or the ancestors, or the elders, who inspire you to continue to do what you do?

I have a number of old prints from Ebony Jet collection on my walls in my office. A number of them remind me of various things. There’s a photo of my dear friend, Dream Hampton, who produced the R. Kelly documentary, gave me, that is Bayard Rustin and James Baldwin and a couple of other folks just looking so cool. It always reminds me about bringing my full self to the table, and who I am at the intersection of all of my experiences and all of my identities, and all of the people who got me to the place I am. There’s a picture that I look at of Malcolm X speaking to a large group of people on 125th Street, and the beautiful part of that picture is that the crowd is huge so it reminds you that you can’t do this work without people. But if you look at the faces of people in that picture, folks are smiling and they’re clapping, and they’re laughing, and it reminds you that there’s got to be black joy in this.

I’ve got colleagues, like Arisha Hatch, who leads our campaign work and our PAC, who constantly remind me of black joy and making sure that we center black joy. Black joy is not the absence of pain, but it is a reminder that we’re not just fighting against stuff, but we are fighting for stuff. Then, there are two pictures when I sit at my desk to my left, one is of Shirley Chisholm talking to a group of students on the Capitol, just a reminder of what it means for people to be brave and chart new territories and be unafraid. It’s a reminder that Color Of Change is an organization that doesn’t take corporate money, or doesn’t take government money; just looking at this woman, this pioneer who talked about what it means to be unbought and unbossed. I don’t know if we can ever fully do that, so that’s not what I’m saying, but I’m saying that it’s an aspiration.

The final picture is this photo of Muhammad Ali and Fannie Lou Hamer sitting and talking. I absolutely love this picture. For me, you have one of the greatest organizers and one of the most famous, prolific cultural figures that ever existed. It’s a reminder of the intersection of organizing and culture change, and a reminder of how those things intersect and what it has meant for black liberation, and black stories. More importantly, what it has meant for the formation of this country. What has made this country great has always been about what black people have been able to bring to the table to remake this country, to bring this country forward. America can love black culture and hate black people at the same time, but those stories, those pictures, those images, for me, remind me that I am but a speck in the legacy of this journey and that every single thing I do has to remember that there were those who were there before me and that there was those who tilled the soil to make this possible.

Photo shoot produced by Christy Havranek. Audio production by Nick Offenberg and Sara Patterson. Grooming by Miyako J Beauty.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Clarification: Language has been amended to more accurately reflect that the circumstances for the cancelation of Bill O’Reilly’s show.

[ad_2]

Source link