[ad_1]

Wandering the pathways at “Time Bomb: The 25th Annual Watermill Center Summer Benefit & Auction.”

NEIL RASMUS/COURTESY WATERMILL CENTER

“OAAEEEAWYAAOOOW!” So shrieked Robert Wilson when a huge balloon, swollen to 10 or 15 feet across, reached its volumetric intake level and burst with a loud, snapping bang. Inflated on a pink stage with little fanfare until its size grew conspicuous, the balloon had been handled by Hee Ran Lee, a Korean performance artist whose piece Blow It! was one of the first that greeted visitors to Saturday’s 25th Annual Watermill Center Summer Benefit & Auction on Long Island, New York.

More startling sounds issued nearby from a paint gun that looked for all the world like an assault rifle of a kind that has become disquietingly familiar to anyone involved in even the most ho-hum American life. That was part of Stephen Shanabrook’s Assaulted Landscape with Splattered Rivers and No Place to Hide, which positioned the artist inside a clear plastic pen from which he took aim at passersby and shot rounds that turned into an eerie sort of painted screed. Elsewhere was grinding, writhing music by the duo Lydia Lunch & Weasel Walter and the clamor of a woman digging her own grave. And then the wonderfully upsetting sounds of teeth knocking and scraping as two mouths took to an angrily animalistic kind of kissing in Basium, a video work displayed on a pair of screens displayed in the woods by Carlos Vela-Prado.

Stephen Shanabrook’s Assaulted Landscape with Splattered Rivers and No Place to Hide.

NEIL RASMUS/COURTESY WATERMILL CENTER

Suffice it to say there was a certain tint of darkness at this year’s Watermill fete. The starry night, for a long time now one of the biggest of the summer in the Hamptons, always has a twisted surreality to it, as dozens of artworks and performance pieces materialize all over the gorgeous grounds of the “laboratory for performance.” But ’tis the season for reasoned brooding and fear, and the artists at work—most of them present or past participants in Watermill’s artist-residency programs—seemed more than a little collectively aware.

Attendees for the evening were greeted with cocktails (Moroccan orange palomas with tequila, cinnamon, and mint) before commencing on a wide-eyed processional around art-studded pathways that wind through grass, gravel, and dirt. Inside Watermill’s “Knee Building”—a room whose floor is made of river stones so as to keep visitors off-balance and conscious of how weird walking can be—was a musical installation by CocoRosie, with haunting woodwind sounds and singing from what seemed to be a cadaver in a boat.

Shoplifter/Hrafnhildur Arnardottir’s Lonely.

RYAN KOBANE/COURTESY WATERMILL CENTER

The performative installation Lonely by the Icelandic artist Shoplifter/Hrafnhildur Arnardottir featured a large pile of brightly colored furs with a pair of bare legs jutting out and slowly striking different poses, like a Busby Berkeley scene misremembered during a psychedelic episode. For Saving Grace, Miles Greenberg & Niles Harris—both in virtual-reality goggles—did a slow contorted dance together over a platform filled with fine pink sand. For her piece Untitled (Double Face), the Israel-born, New York-based artist Naama Tsabar joined a partner to play a grottily distorted electric guitar custom-built with two fused necks (one from a right-handed guitar, the other from a left-). The work “examines the icon of the electric guitar and repositions it in a new gendered history,” Tsabar said.

Over at the grave-digging exercise, in which Genevieve Neve dug her own grave for a piece by Davide Balliano titled I’ll wait for you at the rise of the morning star, onlookers gasped upon the realization of what she was doing. “Oh my god, I love her,” said a woman in expensive clothes. “I totally feel her.”

Genevieve Neve digs her own grave in Davide Balliano’s I’ll wait for you at the rise of the morning star. RYAN KOBANE/COURTESY WATERMILL CENTER

As the cocktail portion of the program turned over to a dinner that helped raise $2.2 million for the Watermill Center over the night, MC duties were assumed by Helga Davis, who starred in the most recent revival of Einstein on the Beach, the opera/theater work that in 1976 put director Wilson (and composer Philip Glass) on a map still being redrawn in all the years since. Brief remarks were delivered Christopher Knowles, who helped write Einstein—and whose painting from years ago lent the evening its theme: “Time Bomb.” (The painting was a memory of the logo of an improbably macabre children’s game marketed by Milton Bradley in the ‘60s, during the era of the Vietnam War.)

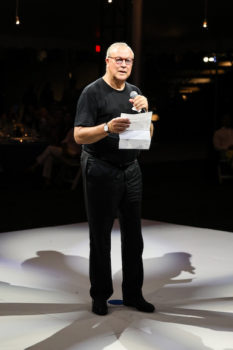

Robert Wilson’s tribute.

NEIL RASMUS/COURTESY WATERMILL CENTER

Then Wilson rose and, after a spell of silence, read a moving tribute to the late Pierre Bergé. The longtime partner of the fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent, Bergé had seen Wilson’s formative 1970 work Deafman Glance (a mostly silent play) in Paris and gave an early donation that helped establish Watermill as the kind of art center it is today. “For your voice, for your mixture of all cultures—for Pierre, a world minister, I say thank you, with love, for now and forever,” Wilson said to his departed friend.

Then came Moroccan food, in what seemed to be a nod to Bergé’s former home in Marrakech, where he developed the Musée Yves Saint Laurent and tended the insanely beautiful Majorelle Garden. And then came time for auction action, with Simon de Pury on the microphone. After recalling a heated auction battle between Lady Gaga and collector Maja Hoffmann at Watermill in the past, he announced the first lot up for sale: a dinner date with Marina Abramović, who stood from her seat and took the stage to go over a few stipulations. The dinner would include “definitely politically-incorrect jokes,” the artist said. And while dining, all the assembled would wear headphones so as to block out surrounding sounds, with time for talking only between courses.

For three days before the meal in question, no one would be allowed to have sex or watch television. And then one rule for the dinner itself: “You can’t talk about Trump.”

The bidding started at $5,000 before rising much higher.

[ad_2]

Source link